Elisabeth Bik is as brave as they come. She has been threatened personally and professionally by people she’s never met, only because she dares to critique some of the most widely read and published scientific papers in the world. The Dutch microbiologist discovered her unique skill of spotting – manually, with her naked eye – plagiarized text and fabricated images that otherwise go unnoticed in peer-reviewed publications.

“It’s almost unthinkable,” she explains, “that peer-reviewed papers contain irregularities clearly altered to arrive at favourable research outcomes. Such acts of misconduct have harmful long-term effects on the scientific community and the public as a whole.”

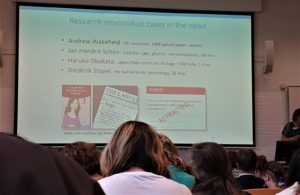

Last week at the European Conference on Science Journalism in Leiden, Netherlands, I attended Elisabeth’s keynote lecture ‘The Dark side of Science: Misconduct in Biomedical Research’. On the surface, Elisabeth struck me as someone analytical and empathetic, and the latter became quickly evident when she said she doesn’t blame researchers who practice scientific misconduct. “Researchers are almost always under immense pressure to publish, so I understand why they may resort to altering their data.”

Why do people cheat in science?

According to Elisabeth, some forms of misconduct are accidental, in that the researcher publishes questionable findings from an innocent mix up of files. Other forms of misconduct, however, are more devious and can question the integrity of both the paper and the researcher. Such misconduct may occur for a number of reasons, including:

- The ease to publish positive results compared to negative findings

- The ‘publish or perish’ system, especially for researchers dependent on work permits abroad

- The number of publications being considered a measure of the researcher’s productivity

- Pressure from senior professors and/or thesis guides to deliver favourable outcomes

Over the last few years, Elisabeth has manually scanned over 20,000 papers in 40 journals around the world. She focuses on scanning images because there are already several tools to identify plagiarism in scientific papers, but nothing reliable enough to detect doctored images. Much to her surprise, her search revealed that nearly 4% of the 20,000 papers (i.e., 800 papers!) contained duplicated or altered images – either in whole or part, that were missed by editors and reviewers during the publication process. So how does she do it?

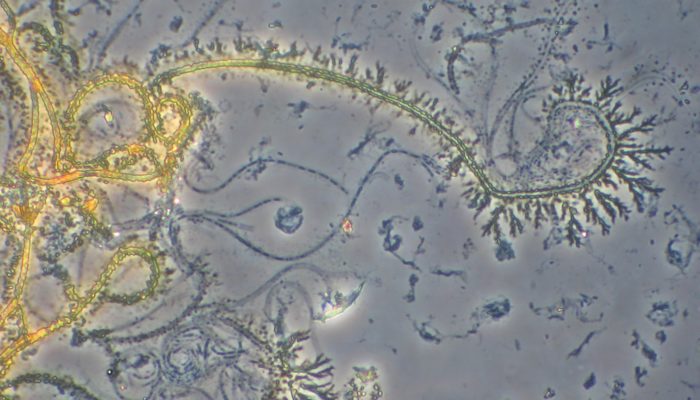

On the huge screen Elisabeth showed us four pictures of bacterial cells stained on glass slides. Each of the four photos are reported as four different experiments in the paper. As a microbiologist myself, I was quick to notice that some sections of the second photo were duplicated in the fourth. When Elisabeth asked if we could spot the duplication, I was joined by a few others who raised hands in the affirmative. “Very good,” she responded encouragingly, informing us that every single blot or line in a scientific image is unique and should be treated as such.

“If it looks like Uncle Larry appears twice in the same photo, it’s most likely a doctored image, that is…unless Uncle Larry has a twin. And what are those odds?”

The three types of image duplication

Images in a scientific study are often central to discussing the findings: they represent the outcome(s) of the experiment and act as key data points – both for the study and for future discussion. As scientists are known to be meticulous with their reporting, Elisabeth says it is highly unlikely for images to be duplicated and represented as different experiments… and yet they are. Over the years, she has observed three types of image duplications in published research papers:

- Simple duplication: where the same image or section of the image is copied into another image

- Duplication with repositioning: where a section of one image is rotated or reversed, and then used to represent a different image

- Duplication with alteration: where an image or section of an image is stretched, zoomed, cut, or edited, and then used to represent a different image

When Elisabeth spots such cases of misconduct, she contacts the Editor in Chief of the journal with her findings and recommends the paper be corrected or retracted. Often this process can take months, and sometimes, even years. But this does little to deter her. Together with her team at PubPeer, a not-for-profit organization, Elisabeth pushes for action to address such cases to limit the long-term impact of these papers.

The harm caused by scientific misconduct

It may seem like a few falsified or altered images are relatively harmless in the grander scheme of things, but the damage they can cause is two-fold: (1) they affect future scientific inquiry, in terms of money, effort and time, as scientists rely on previous studies to contribute to the existing body of knowledge (2) they erode public trust in science or can even foster a divisive society, by presenting inaccurate findings.

During her lecture, Elisabeth reminded us of the many published-and-later-retracted studies that, despite being taken off the public domain, continue to act as the base of misinformation in public health and disease even today. One of the papers with signs of misconduct was cited a total of 342 times, which only after much persistence on her part was finally retracted in 2020.

What you can do to support scientific integrity

Researchers of all levels can play a role in upholding the integrity of scientific publications. If you spot any anomalies in images such as copying, editing, zooming in or out, or repositioning to make the image appear as different pictures or parts of different experiments, there are a few ways you can report your observations:

- Contact the Editor-in-Chief of the journal

- Contact the Research Integrity Officer of the author’s research institution

- Post your findings on PubPeer.com

Some scientists are already doing the right (but difficult) thing – reporting errors in their own published papers which led to the paper being retracted. We recommend reading evolutionary biologist Joan E. Strassmann’s recent blog Retraction With Honor, where she speaks of the importance of intellectual honesty and owning up to mistakes or errors in scientific studies.

At the end, Elisabeth reminded everyone,

“We need more people to be angry about these things [scientific misconduct] and fewer people who try to sweep them under the rug.”

If you want to learn more, you can visit Elisabeth’s blog Science Integrity Digest which includes ‘how to’ guides to spot and report plagiarism, duplicated images, and conflicts of interest in published scientific papers. You can also read our GeoPolicy blog on what scientists can do when policymakers intentionally or accidentally misinterpret or misuse their science.

If you find this blog useful, we encourage you to share it within your scientific circles too, and share your stories in the comments of how you have helped to combat scientific misconduct.