So here is a question: why would anyone want to live in the vicinity of an active volcano? The risks are well known, with hazards arising from lava flows, lahars, ash falls, debris avalanches, and pyroclastic density currents, with many often having deadly consequences. But despite the danger, more than half a billion people live in the direct vicinity of volcanoes. Could it be that communities proactively choose to settle in areas surrounding volcanoes; and if so, why? That is the very question research published earlier this year in the EGU open access Journal, Natural Hazards and Earth System Science (NHESS), seeks to address.

The team of scientists, led by Syamsul Bachri, a researcher at the University of Innsbruck, approach the question from a novel angle. Often, when studying hazards and risk management strategies associated with volcanoes, the focus is on the volcano itself, with researchers commonly taking a very scientific approach to the problem. Instead of focusing on how people are able to adapt to living near the constant threat of an erupting volcano, the new study takes a more holistic view: perhaps a volcano presents opportunities as well as hazards, and society and nature are complexly interlinked?

Previous studies of a similar nature found that people often live in hazardous regions due to a lack of hazard knowledge, a lack of alternatives and/or because they are forced to due to a marginalised social status. However, the new study considered a new option: ‘upside risks’, or opportunities, may offset some of the downsides of living in hazardous areas and should be taken into account in disaster risk reduction and management strategies.

In order to fully understand the complex interaction between humans and volcanoes the researchers used an approach which bridges social and natural sciences. They conducted a series of interviews and focus groups with communities living around Mt. Bromo in Java, Indonesia.

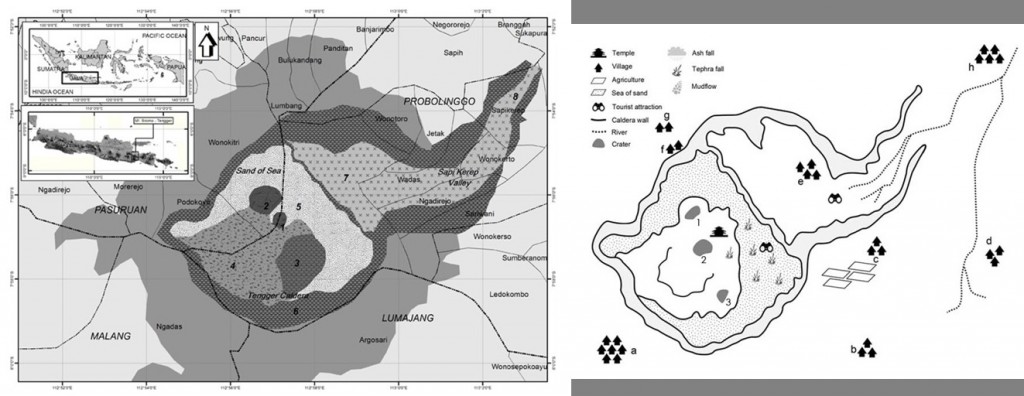

(Left) Bromo Volcano and its landforms: (1) Gunung Bromo and its crater; (2) a Strombolian cone, Gunung Batok; (3) complex of rest volcanic cone (G. Kursi); (4) complex of rest volcanic cone (G.Widodaren) and SegaraWedi; (5) Sand of Sea ; (6) Tengger caldera formation (upper and middle slope); (7) foot slope of Tengger caldera (Sukapura Barranco); (8) Sapi Kerep outlet valley (interpretation from SRTM

Image and field survey.) (Right) Human–volcano system at Bromo Volcano. (1) Mt. Batok, (2) Bromo Volcano, (3) Mt. Kursi, (a) Ngadas Village, (b) Ranupane Village, (c) Ngadirejo Village, (d) Sumber Village, (e) Ngadisari Village, (f) Wonokitri Village, (g) Tosari Village, (h) Wringinanom Village. From Bachri et al., 2015. (Click to enlarge).

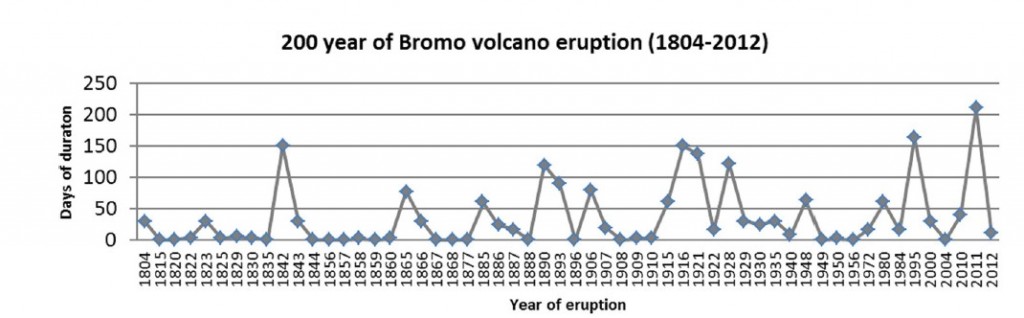

The volcano has erupted 56 times since 1804 and continues to be active today. The most recent eruption took place in 2010, and was sustained over a period of nine months. The estimated total economic loss was valued at USD ~15.5, affecting agriculture and the tourism industry, as well as causing significant loss of property. Disruption caused to the electricity supply, transport and water availability is more difficult to quantify. In total, 70,000 people, across 33 villages were affected by the eruption.

The communities living around the volcano are known as the Tenggerese, a Javanese ethnic minority, counting a population of about 600,000. The Tenggerese consider Mt. Bromo a deity and symbol of their culture. At lower altitudes, on the flanks of the volcano, they cultivate the fertile volcanic soils and raise livestock, while at higher altitudes they live as nomadic herds.

Despite the significant disruption caused to the Tenggerese by the 2010 eruption, the interviews conducted by the researchers revealed that the local communities benefited from the main resulting hazards: tephra fall, lahars and landslides. They found that the communities felt the effects of the eruption were negative whilst the eruption was ongoing and for a short period after. However, once the short-term disruption ended, the overall perception was one where the hazards presented opportunity.

Year and duration (days) of Mt. Bromo eruption in a 200-year period (for 1804–2010, CVGHM 2010; and for 2011–2012, Field

survey, 2012). From Bachri et al., 2015. (Click to enlarge).

Areas covered by volcanic ash and fine rock material could not be planted for two years following the eruption, but areas covered only by fine volcanic ash became more fertile. The Tenggerese farmers referred to this as Berkah Bromo (Bromo’s opportunity), and stated that Mt.Bromo provided benefits for the continuity of their livelihood.

The eruption also caused a number of lahars – volcanic mud flows known locally as lahar hujan – which destroyed some 20 houses. Despite the short-term negative effects of the lahars, agricultural productivity in the affected region was increased and is already being exploited by the local farmers. Bapak Kirno* (the head of Wrininganom village) stated during the interviews:

“Areas which are affected by lahar hujan from Bromo will be more fertile after some period if they are not dominated by sand materials.”

Landslides caused significant disruptions, in particular causing road accessibility problems, but at the same time, transferred fertile materials to new areas, contributing positively to soil quality.

(Top) Tenggerese priests during Dutch East Indies era which lasted from 1800 to 1949. (Bottom left) Tenggerese woman with two children. (Bottom right) Tenggerese priest holding a dedication ceremony of a new build house. (images provided to Wikimedia Commons by the Tropenmuseum, author unknown). Click to englarge.

The research also found that volcanoes are a powerful force in shaping cultural identity. The essence of who the Tenggerese are is intrinsically linked to Mt. Bromo and they have a deep spiritual connection with the volcano. The Tenggerese believe that the attitude they have towards the mountain will play a role in how Mt. Bromo behaves towards them. Bapak Wahyu*, a participant of a focus group discussion, considers that the unusually sever 2010 eruption was a result of the abandonment of old customs. The younger generations used the benefits from plentiful agricultural yields, not to save in the traditional fashion, but to purchase unnecessary consumer gadgets. He argues this left villager’s ill prepared, with insufficient resources to survive the sustained eruption.

The interviews and focus groups allowed Bachri and his team to identify five ways in which the Tenggerese have culturally adapted to living in the shadow of Mt. Bromo and which have also enhanced their life. They have, not only a heightened resilience to hazards, but a greater capacity to recover from them, too. The limited and unique extent of the territory they inhabit gives the Tenggerese a strong local attachment and a deep knowledge of the hazard posed by the volcano. At the same time, their proximity to the volcano instils a sense of social and moral order and allows them to frame and voice dissent in a larger cosmological setting. Finally, volcanic eruptions are often the catalysts for change and this is largely viewed positively by the local inhabitants.

“I am never scared of Bromo’s eruption because I always believe that this is temporary. Bromo’s eruption always benefit us. We believe that Bromo always gives us what we need to live here,” says Bapak Rudi*, Ngadirejo village official.

*All names used in the study were changed to protect the identity of the informants.

By Laura Roberts Artal, EGU Communications Officer

References

Bachri, S., Stötter, J., Monreal, M., and Sartohadi, J.: The calamity of eruptions, or an eruption of benefits? Mt. Bromo human–volcano system a case study of an open-risk perception, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 15, 277-290, doi:10.5194/nhess-15-277-2015, 2015.

Tilling, R.I.: Volcano hazard, in: Volcanoes and the Environment, edited by: Mart, J. and Ernst, G., Cambridge University Press, United States of America, 55-90, 2005.