In this third instalment in this series our journey takes us into the Skeleton Coast. Synonymous with shipwrecks and known as “The Land God Made in Anger” to indigenous Bushmen this coastal desert has been protected as a National Park since 1971. Similar to many of Namibia’s National Parks, the Skeleton Coast does not allow anyone to stay overnight within its boundaries. However at over 16,000 km2 rarely any of the public is able to experience much of the landscape on the ground beyond the 120 km salt road in its southern section. This coastline is inundated with fog for most of the year owing to the cold Benguela upwelling, which cools the overlying air. In contrast, dry conditions prevail when ridging high pressure systems south of southern Africa cause strong, offshore winds.

From Swakopmund with a support vehicle full of supplies one vehicle started the journey north up to the top of the Skeleton Coast on the lonely salt road to meet with the Park Ranger to go over recommended routes and safety concerns (you can get a feel for the drive watching this time-lapse video of drive from Swakopmund to Skeleton Park Gate). The following morning the support vehicle, with the now fully functional trailer, headed up the coast packed with 6 full weather stations to meet with the other vehicle on its way back from Möwe Bay at a prearranged location near the mouth of the Huab River. However, without cell phone signal since the early hours of the morning, assumptions had to be made on how each group were getting on. As it turns out, the group coming back from the ranger station had experienced an incident with their vehicle where the rear passenger wheel had ripped off the vehicle completely around 20 km south of Terrace Bay. The group coming from the south decided to look for them around midday after realising that something must have gone wrong for them to be so late. They found them on the side of road with a 60 m long trench coming out of the back of the car from the hub dragging along the ground. Through some quick reorganising and a call to a mechanic back at Terrace Bay, the vehicle was restored to a working condition and we headed south to the Huab River the following day.

The Huab River is a very remote and narrow river system that has one of the larger drainage systems of the dry valleys along the Skeleton Coast. The system is composed mainly of the Karoo-aged Etjo sandstones in the interior and volcanic-derived dolerite sills near the coast (including many exposed dolerite pipes). T here is a multitude of other landforms in the valley though, including nebkhas, barchans dunes, coastal sabkhas, quartz gravel plains, and gravel/boulder covered desert pavements. A most amazing scene to be located for fieldwork, but also the most demanding – after a long day of hauling equipment around you are on your own to build a campfire to cook food and brave the cold dry desert air (or in a couple cases the cold foggy coastal air) in tents overnight.

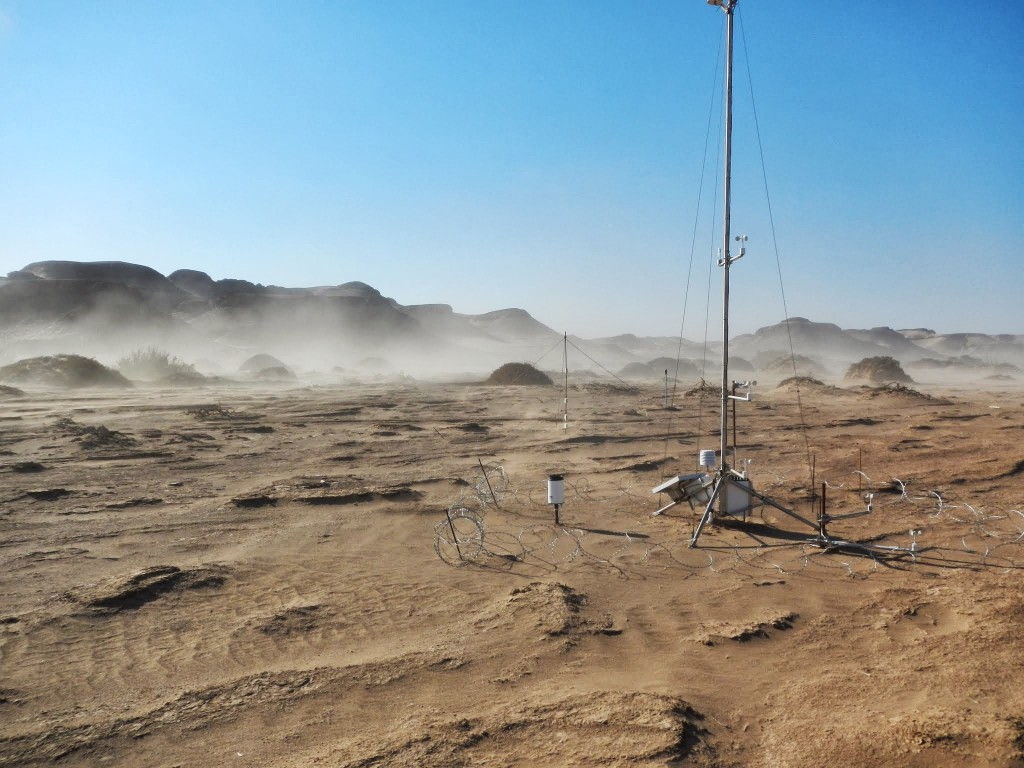

The dust monitoring weather stations installed here follow a narrow single-track ranger road that is almost completely erased by the wind-driven shifting soil and sand. This required very careful 4×4 driving that had the vehicles going up and over active sand dunes, alluvial fans, two to three metre high river terraces, and along coastal beaches. The site farthest up the valley (about 30 km from the ocean) takes around 2.5 hours to get to from the public coastal road and is located on an extensive desert pavement soil intended to be a clean and dust–free upwind site.

The treacherous driving conditions along the Huab River, here navigating the older river terraces. (Credit: A. Dansie)

The stations down the valley consisted of one on the older active fine river sediments now surrounded by desiccated nebkha dunes and other sparse vegetation remnant of a wetter period in time. It also provided an area for our campsite just across the most recent active river channel. Its location, still quite inland, should help test that the majority of dust transported from this valley originates from recent river deposited sediments showing the reliance of arid processes on river sediment delivery. A visit the next week did just this as seen in this time-lapse video of the site from the car of a local dust event.

The rising moon over one of the weather stations photographed from the campsite. (Credit: A. Dansie)

The sites closest to the ocean consisted firstly of another sandy nebkha site close to an active spring; which could prove a good test of the razor wire to protect the instruments from inquisitive animals. Another site located in the much wider groundwater fed channel system was installed the following week and included one of the Cimel Photometers that measures the amount the sun is obscured by aerosols. And lastly, a beach site located only 50 metres from the ocean surf at high tide that may well be an area of high sediment transport(but not from the continental dry easterlies rather from the predominant coastal on-shore winds never known for producing dust emissions).

The weather station closest to the active spring. Dust emissions in the background are from a south-westerly wind never previously thought to be able to drive dust emissions. (Credit: F. Eckardt)

This route of sites will be visited monthly over the austral winter to download data, change dust monitor filters, empty sediment traps, inspect for damages, and keep a record of the dusty days to coordinate with the others on the project. One such visit was just performed and within two weeks all sites were successfully visited, although not without getting the 4×4 stuck for an afternoon in the Tsauchab River sands, taking a day to repair damages from a Hyena, and enduring a series of cold, foggy, and windy days in the Huab.

Come October the project will hopefully join the very lonely group of projects that have successfully collected dust storm emissions data at a remote source location!

You can follow the project’s progress through their twitter account @DO4Models.

The installation crew enjoying the camp fire after a long hot day in the field. (Credit: R. Washington)

By James King, University of Oxford

Want to catch up on the rest of the Dust in the Desert series? Take a look at Part 1: Measuring it is only half the battle and Part 2: The Kuiseb and Tschaub Rivers.