The oceans are a big contributor to the global carbon cycle, with phytoplankton taking up carbon through photosynthesis and incorporating it into their shells. When these organisms die their shells sink and make a calcareous contribution to seafloor sediments. Of course, with the formation of limestone, this carbon is locked out of the atmosphere for long periods of geological time.

Until recently, the Arctic Ocean was not considered to be a big player in the ocean carbon pump. This was because phytoplankton here experience relatively low light levels and extensive ice cover limits carbon exchange with the atmosphere. However, the reduction in ice cover experienced in recent decades means that phytoplankton are being exposed to sunlight for much longer periods. This means that phytoplankton blooms are also occurring earlier in the year, with an increase in primary productivity. In fact, the Arctic Ocean is responsible for about 14% of the global uptake of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere! Take a look at all that chlorophyll:

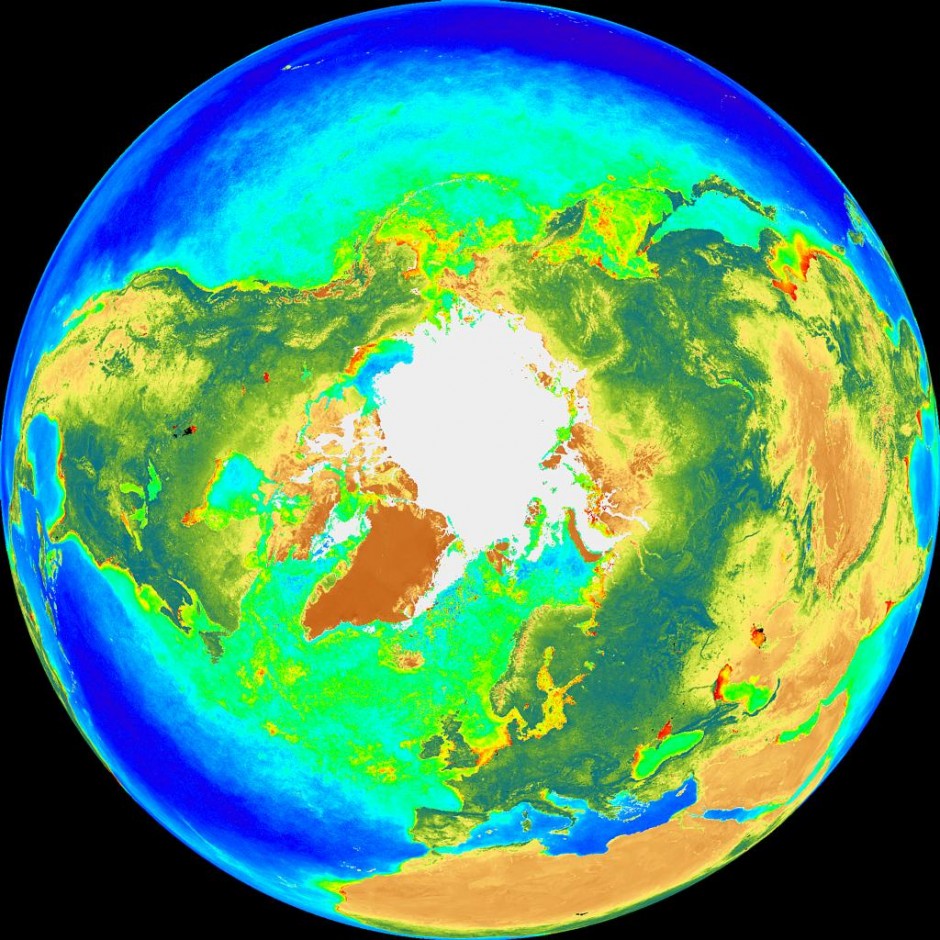

Chlorophyll concentration in the Northern Hemisphere. (Credit: NASA)

Remote sensing plays a big part in finding out this information. Satellite images let us take a look at ocean colour – a measure of the ocean’s ‘greenness’ – the greener the ocean, the more chlorophyll is present in the surface water. If there’s more chlorophyll, then there will be more phytoplankton busily converting sunlight into energy and fixing atmospheric carbon in the process.

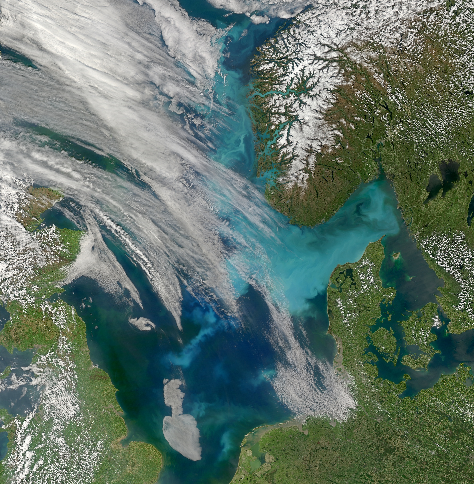

Coccolith bloom in the Skagerrak. The white calcareous shells of coccolithophores is responsible for the milky colour of this coastal water (Credit: NASA/MODIS/SeaWiFS)

This increase in primary productivity means that the Arctic Ocean is fixing more carbon than before, but changes in light availability are not the only thing helping Arctic plankton fix more carbon…

Strong stratification of the water column (with fresher, less dense water on top and more saline, higher density water on the bottom) prevents nutrients from mixing into the photic zone throughout most of the year. But there’s another source of nutrients phytoplankton can make use of – these are transported into ocean basins via estuaries and give a big boost to productivity in the surface ocean. You can see this from space as coastal waters are greener (more phytoplankton-rich) than waters further offshore. The same is true in upwelling zones, where deep, nutrient-rich water is brought to the surface.

This is a false colour image of chlorophyll concentration. Dark blue regions are low nutrient, low chlorophyll environments and red regions indicate areas where algae have reached harmful levels – note that these areas hug the coastline, where nutrient input is greatest. (Credit: NASA)

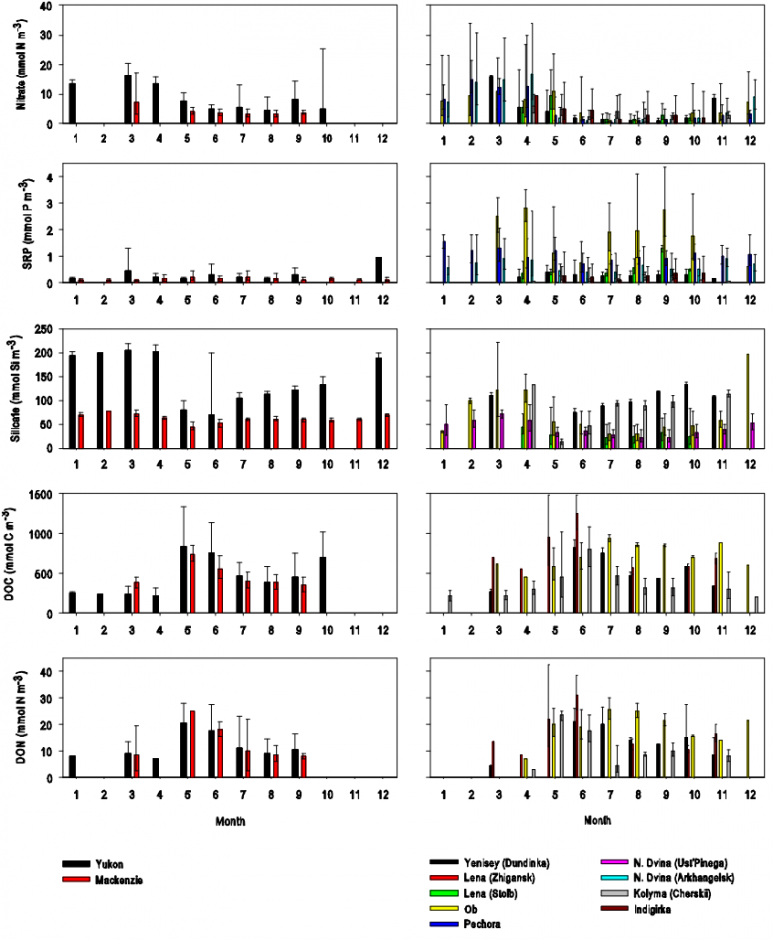

While the Arctic isn’t a major upwelling zone, 10% of the world’s freshwater flows into the Arctic basin, which makes up only 1% of the global ocean volume. This large freshwater flux has the potential to bring a large quantity of nutrients and stimulate phytoplankton growth, something that Vincent Le Fouest and his colleagues set out to explore. By taking nutrient measurements (nitrate, phosphorous and silicate, amongst others) for several rivers entering the Arctic basin they established a historical baseline of river fluxes into the Arctic Ocean. This can be used assess their impact on the biogeochemistry of shelf waters in the future.

A snapshot of some of the baseline data for rivers entering the Arctic Ocean (click for larger). (Credit: Le Fouest et al., 2013)

Despite the potential that riverine nutrients have for stimulating phytoplankton growth in the Arctic Ocean, it is still nitrogen-limited. While the river flux has no effect on phytoplankton growth here, this may not always be the case, as the flux of riverine nitrate is ever-increasing as larger populations put more pressure on local water resources and increasing waste and agricultural runoff enters the river system.

Future trends in Arctic primary productivity are dependent on nutrient input into the photic zone and we can only quantify these changes with a baseline dataset such as this one.

The baseline data collected by Le Fouest and his team is published in Biogeosciences and you can access it free of charge here.

By Sara Mynott, EGU Communications Officer

Reference:

Le Fouest, V., Babin, M., and Tremblay, J.-É.: The fate of riverine nutrients on Arctic shelves, Biogeosciences, 10, 3661-3677, 2013.