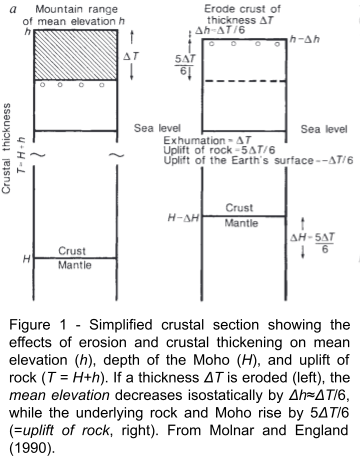

With this paper, England and Molnar (1990) shed light on the recurrent confusion in the uses of terms ‘uplift’ and ‘exhumation’. The main focus is to clarify the difference between surface uplift, uplift of rocks, and exhumation by explaining the differences and the relations between these processes (Fig. 1). The manuscript also illustrates how other processes, such as changes in climate, can be mistaken for surface uplift. Examples of cases in which these concepts were mistaken are reported from the literature.

The first key point of the contribution concerns the dynamics of mountain ranges. Surface uplift of mountain ranges such as the Tibetan plateau represents isostatically compensated changes in crustal thickness. Crustal thickness generally gives an indication on the tectonic ‘driving force’ responsible for mountain building, but it can also be reduced (i.e., reduction of potential gravitational energy) by isostatically compensated exhumation, which in turn can result from tectonic activity or from erosion.

Another key point is that several reported rates of surface uplift in the Himalayas and Andes are too rapid to be explained by crustal thickening. Although the authors point out potential mistakes in the way these estimates were obtained, they highlight that, if correct, reported surface uplift estimations would give important constraints on the behavior of continental lithosphere and its underlying mantle.

The paper by England and Molnar (1990) is well-cited by the TS community, probably as it is one of the first papers to clearly define the different connotations of uplift, and the important difference between surface uplift, rock uplift, and exhumation. It is noteworthy that the paper has provided an important basis for a broad range of research topics, including seminal papers on mantle dynamics (e.g., Molnar et al., 1993), thermochronology (e.g., Reiners and Brandon, 2006), and paleoclimate (e.g., Hoorn et al., 2010). Apart from the obvious value encountered in scientific literature, the high readability of this paper – very conceptual and understandable – has helped teach many students about some of the basics in the tectonic implications of vertical motions.

In the Reddit discussion – feel free to add your thoughts – Gino de Gelder, Akinbobola Akintomide, and Silvia Crosetto notice how the uplift-analysis challenge is still true nowadays, being it related either to interpretation or to the methods employed, showing how the paper is a timeless Must-Read paper.

In the estimation of surface uplift, preservation of the uplifted surface is a key factor. Akinbobola reports an example in Papua New Guinea Finsetree mountains, where a limestone and its fossil record were spared from erosion and could be used to reconstruct the paleotopography (Abbott et al., 1997). Another known issue in uplift studies emerged from the discussion is multi-phase or non-constant uplift. In the discussion were mentioned, among potential examples of non constant uplift, the two phases of surface uplift, Late Miocene and Pleistocene, reported for the Central Anatolian Plateau in Turkey (e.g., Schildgen et al., 2014), and the short-term yo-yo vertical motions observed in correspondence of subduction margins (e.g., Wang, 2007). These examples remind us that uplift is not always constant, and is therefore important to identify all the uplift phases if we want to prevent underestimating the uplift rates.

Written by Silvia Crosetto, Gino de Gelder, Akinbobola Akintomide, and the TS Must Read team

References:

Abbott, L. D., Silver, E. A., Anderson, R. S., Smith, R., Ingle, J. C., Kling, S. A., Haig, D., Small, E., Galewsky, J., and Sliter, W. S., 1997, Measurement of tectonic surface uplift rate in a young collisional mountain belt: Nature, v. 385, no. 6616, p. 501-507, https://doi.org/10.1038/385501a0

England, P., & Molnar, P. (1990). Surface uplift, uplift of rocks, and exhumation of rocks. Geology, 18(12), 1173–1177, https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1990)018%3C1173:SUUORA%3E2.3.CO;2

Hoorn, C., Wesselingh, F. P., ter Steege, H., Bermudez, M. A., Mora, A., Sevink, J., Sanmartín, I., Sanchez-Meseguer, A., Anderson, C. L., Figueiredo, J. P., Jaramillo, C., Riff, D., Negri, F. R., Hooghiemstra, H., Lundberg, J., Stadler, T., Särkinen, T., & Antonelli, A. (2010). Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science, 330(6006), 927–931, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1194585

Molnar, P., England, P., & Martinod, J. (1993). Mantle dynamics, uplift of the Tibetan Plateau, and the Indian Monsoon. Reviews of Geophysics , 31(4), 357, https://doi.org/10.1029/93RG02030

Molnar, P., England, P., 1990. Late Cenozoic uplift of mountain ranges and global climate change: chicken or egg? Nature 346, 29–34, https://doi.org/10.1038/346029a0

Reiners, P. W., & Brandon, M. T. (2006). Using thermochronology to understand orogenic erosion. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 34(1), 419–466, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.earth.34.031405.125202

Schildgen, T. F., Cosentino, D., Bookhagen, B., Niedermann, S., Yıldırım, C., Echtler, H., Wittmann, H., and Strecker, M. R., 2012, Multi-phased uplift of the southern margin of the Central Anatolian plateau, Turkey: A record of tectonic and upper mantle processes: Earth and Planetary Science Letters, v. 317-318, p. 85-95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.12.003

Wang, K. (2007). 17. Elastic and Viscoelastic Models of Crustal Deformation in Subduction Earthquake Cycles. In The seismogenic zone of subduction thrust faults (pp. 540-575). Columbia University Press, https://doi.org/10.7312/dixo13866-017