These blogposts present interviews with outstanding scientists that bloomed and shape the theory that revolutionised Earth Sciences — Plate Tectonics. Get to know them, learn from their experience, discover the pieces of advice they share and find out where the newest challenges lie!

Meeting Anne Davaille

Anne Davaille majored in Physics and continued with a PhD in Theoretical Physics of Fluids, jointly at the University Pierre et Marie Curie and the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (IPGP). She investigates convection in strongly temperature-dependent fluids. After her PhD, she went to Yale for a postdoc and she currently holds a CNRS-position at the FAST Laboratory of University Paris-Sud, France.

Research is ideas plus craftmanship. It should be fun and you have to enjoy it to do it.

Anne Davaille. Credit: Anne Davaille.

Anne, what are your research interests and what methods do you use for your research?

Fluid mechanics is my main research area. I study convection in complex fluids, and I use this framework to understand mantle convection and the convective evolution and cooling of planets. My main approach is through laboratory experiments. But then I use and/or build some theory to interpret the experimental results, to derive a physical understanding, and finally to make inferences for geodynamics. All the way, numerics are also involved, to treat the experimental results, or to quantitatively apply the results to planets.

No matter what fancy stuff you do, if your data is not good, you are losing on what you are going to get

You have significantly advanced fluid dynamics within the geosciences. Up until now, what do you consider your biggest scientific achievement?

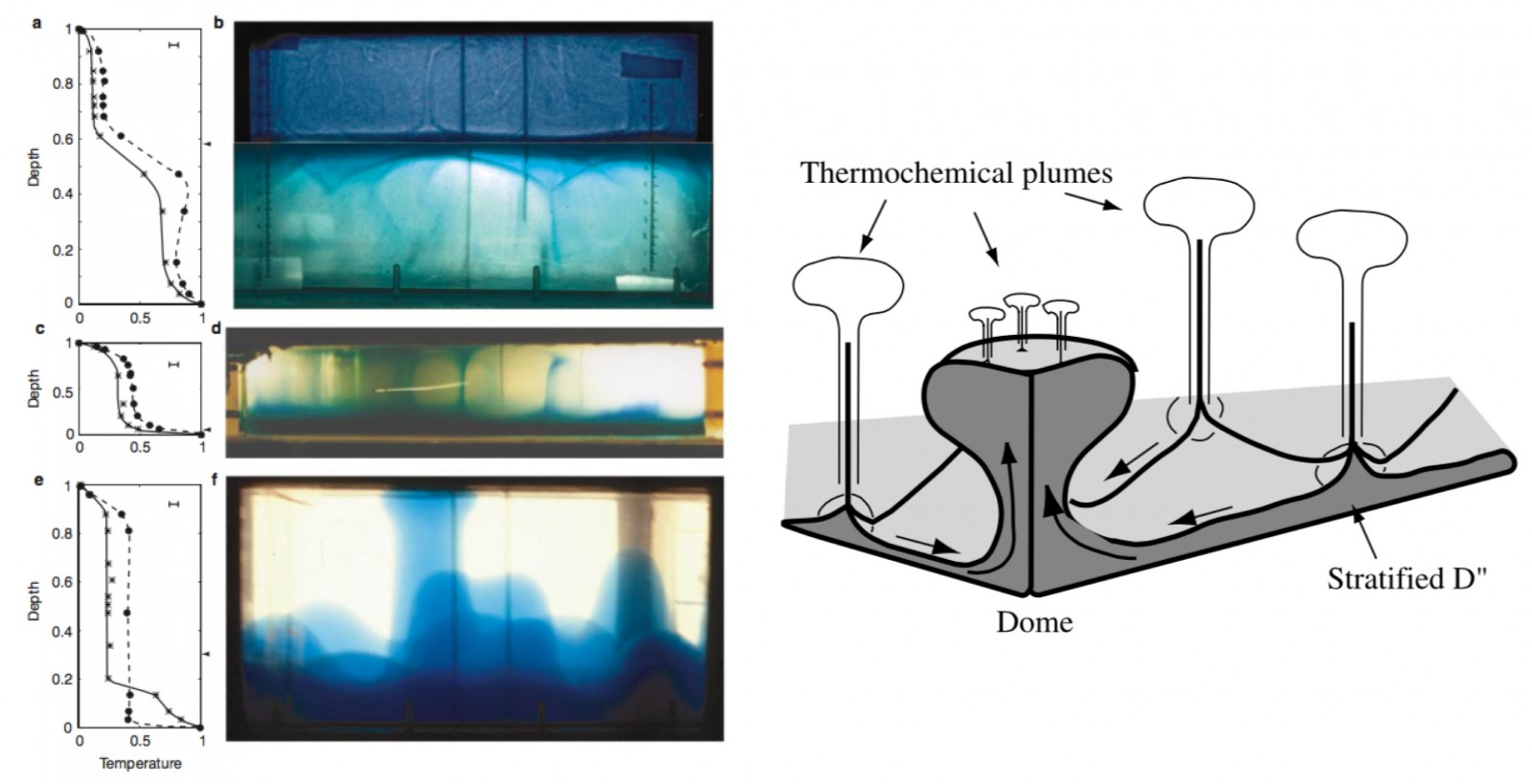

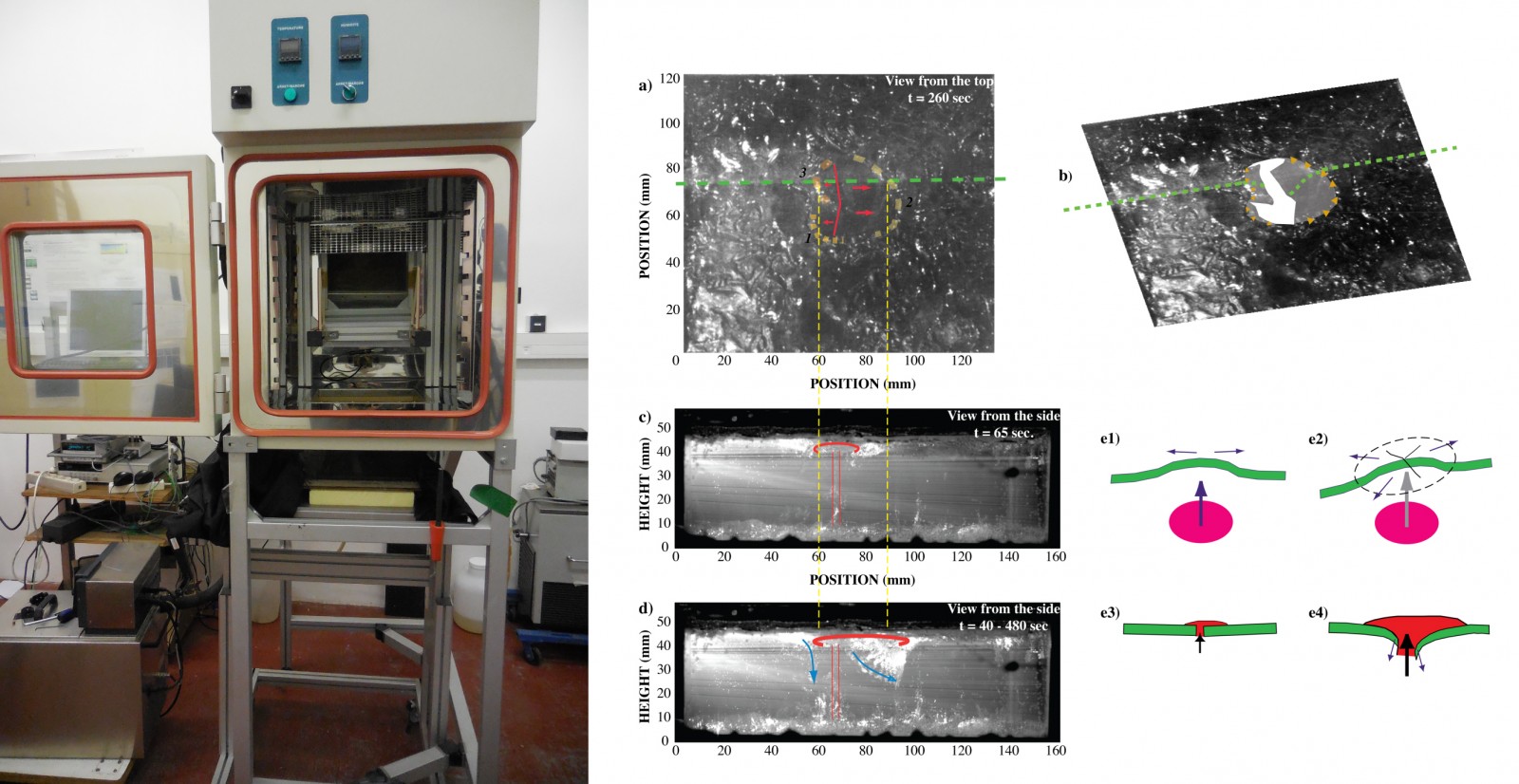

It is probably the works that we did on thermo-chemical plumes in two-layer convection models. We showed that convection in a mantle heterogeneous in density and viscosity could produce several types of plumes, and therefore several types of hotspots. More recently, we have been able to observe different ways of subduction initiation from convection in complex fluids. Plume-induced subduction could be occurring on Venus right now, and might have been important in the Archean Earth. On the side, I am also very happy with the techniques we developed to measure simultaneously and in situ the temperature and velocity fields in the experiments. It really helped us to push lab experiments forward and get a quantitative understanding of the processes we observed.

Different types of plumes and hotspots, depending on the presence of density heterogeneities in the mantle. From Davaille, Nature, 402, 756-760, 1999; and Davaille, Girard & Le Bars, EPSL, 203, 621-634, 2002.

After all the time you have spent in science, you have seen many questions answered and more questions rise. What is the biggest challenge in your field that we face today?

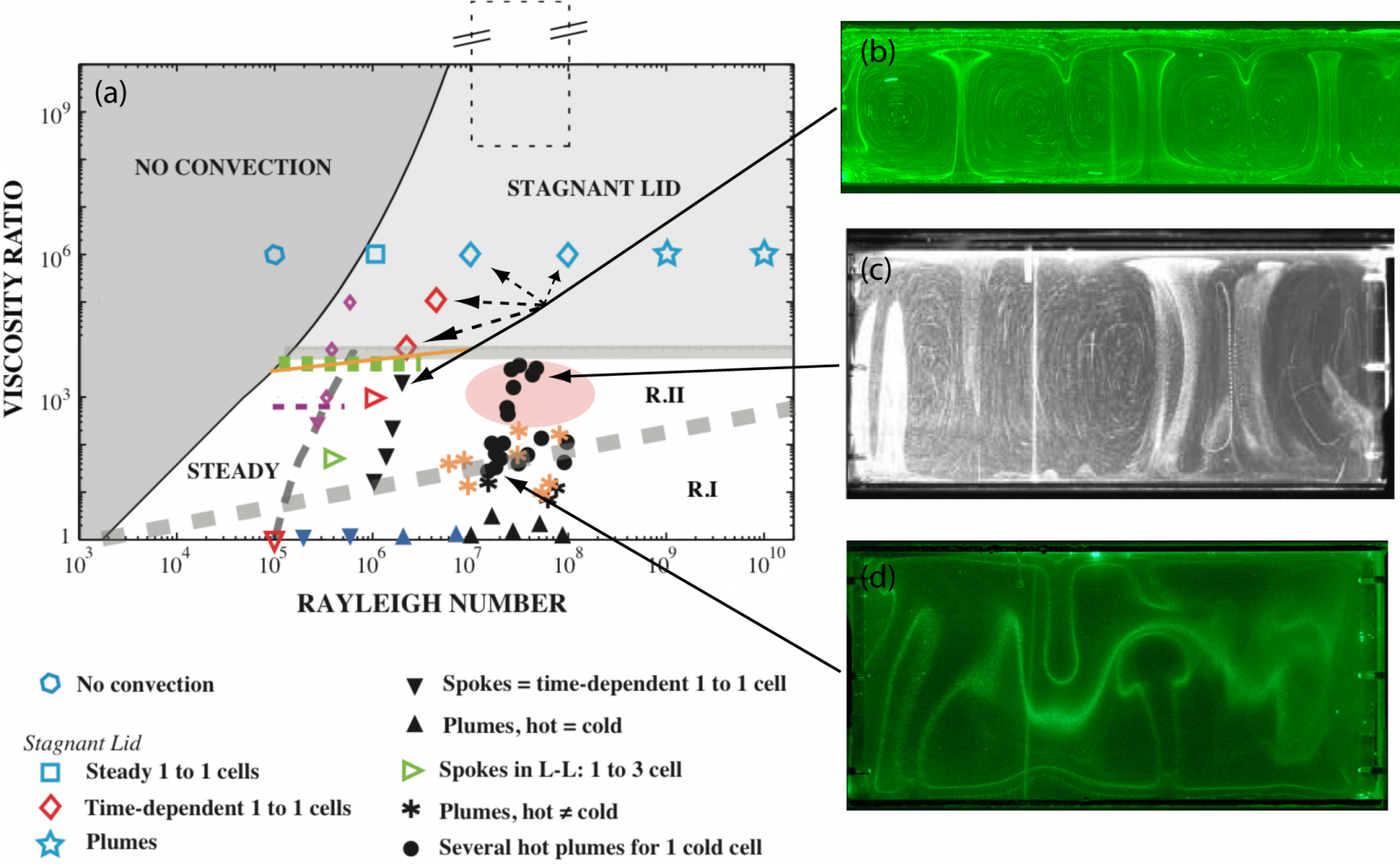

Until now, we still have not solved the question ‘why do we have plate tectonics?’ from a physical point of view. On what scale do we need to look for that answer? Grain scale? Or meso-scale, since the lithosphere is quite heterogeneous (e.g. faults, dikes,…)? To get plate tectonic behavior, and therefore the strong localization of deformation, we need a non-Newtonian rheology. From my experience, fluids presenting this particular behaviour are very often mixtures, and their effective behaviour on the large scale can be quite different from their local microscopic behaviour. Moreover, the history of this structure can also strongly influence the large-scale behaviour. With the theoretical understanding we have today, we still cannot model well these behaviours, and therefore answer the plate-tectonics question. I don’t know if we shalll find the answer in theory first, I don’t think that is necessary. It will require most probably a mix of theory, numerics, and data, both experimental (where you can observe and measure all the scales, from the grain to convection) and geological (the “field truth”). Once we do have that answer, we shall gain a better understanding of the other planets and satellites as well.

Plume-induced subduction obtained in FAST laboratory in a climatic chamber. From Davaille, Smrekar & Tomlinson, Nature Geosc., 10, 349-355, 2017.

The one thing we really should stop doing is having this frantic will to publish

Your field of expertise has changed over the years. Is there something you would still like to change?

Oh yes, there are some things I would like to change. The one thing we really should stop doing is having this frantic will to publish. It is an extremely bad habit and it does not generate good research. Especially for the young people that still need to develop ideas and skills, they need time to think and make mistakes, which is not possible with the current mindset of fast publishing. Fast publishing is not beautiful, nor efficient for creative research. Even though the world wants things always faster, doing it faster is not human. We should stop this. What I find the most important is that my work should be strong enough so that people understand what I did and can use this to build on it and move further. For this we need time.

Different regimes of convection in strongly temperature-dependent fluids as a function of the viscosity ratio and the intensity of convection (Rayleigh number). The temperature structure in the sugar syrups is visualized by Thermochromic Liquid Crystals. From Androvandi, Davaille, Liamre, Fouquier & Marais, Phys. Earth Planet. Int., 188, 132-141, 2011.

When you were in the Early Stages of our career, what were your expectations for your future?

When I was 7 years old, I learned about plate tectonics. Later, the operation FAMOUS was happening and at this young age I found that fantastic and I wanted to know more. That was one of the reasons why I went into physics. I think that during my career I have been very lucky. Once I got my degree, I thought that before getting a job, I wanted to do a PhD in a very specific topic ‘Convection in complex fluids and planets’. After that we would see. I did not really have any expectations, but I thought, if I can do it maybe it will work and that would be great. Somehow it worked and so I continued working in it, and it is still great fun!

You have to be very demanding, very rigorous if you want to succeed

The last question for today’s Early Career Scientists: what advice would you like to give the ECS that would like to stay in science?

Well, first I think that research is ideas plus craftmanship. It should be fun and you have to enjoy it to do it. But craftmanship is demanding. I have a small anecdote here. I once did an internship at Schlumberger. I worked with experiments and my supervisor at the time told me ‘if you put shit in, -(meaning noise)-, you will get shit out’. My advice would therefore be that no matter what fancy stuff you do, if your data is not good, you are losing on what you are going to get. So for experimental or numerical modelling, if you are not demanding, or only short-term, you may get away with it for a while, but on the long run, you will not last. You have to be very demanding, very rigorous. I think that’s the best way to succeed.

Anne Davaille. Credit: Anne Davaille.

Interview conducted by Anouk Beniest