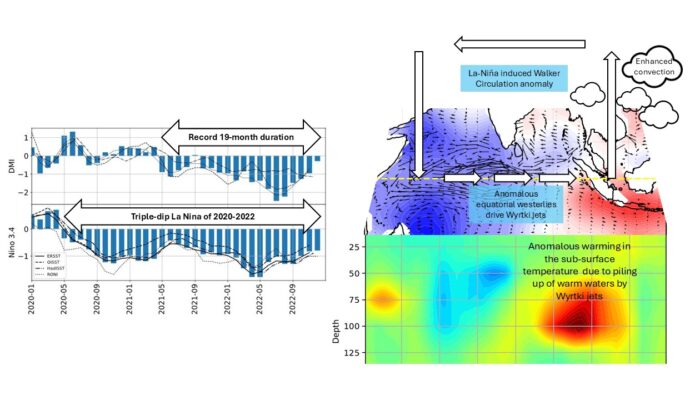

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is generally considered a seasonal mode of variability, developing and decaying within a single year. During 2021–2022, however, negative IOD conditions persisted for approximately 19 months (Figure 1, top left), making this event the longest—and among the strongest—observed since reliable records began. This unusual persistence highlights important aspects of ocean–atmosphere coupling and raises new questions for climate predictability in a warming world.

Published in Weather and Climate Dynamics, we document this extraordinary climate event in the Indian Ocean—a multi-year negative Indian Ocean Dipole (nIOD) that persisted for an unprecedented 19 months, from mid-2021 to late 2022.

What Is the Indian Ocean Dipole?

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is a mode of climate variability driven by differences in sea surface temperatures (SSTs) across the tropical Indian Ocean. In its negative phase (nIOD), the eastern Indian Ocean becomes anomalously warm while the western basin cools, altering large-scale atmospheric circulation. These changes influence rainfall, winds, and extreme weather across regions extending from East Africa to South Asia and Australia.

A Prolonged Negative IOD Event: Why It Matters

Typically, IOD events develop during boreal summer, peak in autumn, and decay rapidly by winter. What makes the 2021–2022 event remarkable is both its longevity and intensity:

- nIOD conditions began in May 2021 and persisted until early winter 2022, lasting about 19 months—the longest duration observed since reliable records began in the 1960s.

- The 2022 peak ranked among the strongest negative IOD events on record.

Such prolonged negative phases are rare and significant because they can interact with other climate systems, influencing regional weather patterns far beyond the Indian Ocean basin.

The Ocean–Atmosphere Dance

Our analysis shows that this multi-year event was not a simple fluctuation but resulted from interacting oceanic and atmospheric processes:

- Persistent westerly wind anomalies dominated the tropical Indian Ocean throughout 2021 and 2022, sustaining warm SSTs in the eastern basin and reinforcing nIOD conditions.

- Westerly Wind Bursts (WWBs)—short-lived but intense episodes of anomalous west-to-east surface winds—occurred with unusually high frequency and duration during this period.

- These winds strengthened Wyrtki jets, which are strong, transient eastward surface currents that develop along the equator during the boreal spring and autumn transition seasons. Driven by anomalous westerly winds, Wyrtki jets transport warm surface water from the western to the eastern Indian Ocean, deepening the eastern equatorial thermocline and increasing upper-ocean heat content.

- The record number and persistence of WWBs during 2021–2022 intensified Wyrtki jets, resulting in deeper thermocline conditions that favored the persistence of the nIOD.

- The nIOD also co-occurred with a triple-dip La Niña event (Figure 1, bottom left) in the Pacific (2020–2022), a rare sequence that likely amplified westerly wind anomalies over the Indian Ocean.

This ocean–atmosphere interplay highlights the strong interconnection between ocean basins and demonstrates how anomalies in one region can reinforce extremes in another. This is illustrated in the schematic (Figure 1, right).

Ocean Memory

Another key insight from the study is the role of ocean memory. The Indian Ocean retained subsurface heat anomalies generated during the 2021 phase, which preconditioned the basin for the re-emergence of the nIOD in 2022.

Under normal conditions, seasonal wind reversals and thermocline adjustments help erase IOD-related anomalies. During this event, however:

- Thermocline anomalies remained unusually deep in the eastern basin

- Subsurface heat content anomalies persisted

- Seasonal feedbacks that typically terminate IOD events were ineffective

Together, these processes allowed the climate system to “remember” the previous year’s state, enabling a rare multi-year continuation.

What Did It Mean for the Monsoon?

The prolonged nIOD also influenced the Indian summer monsoon:

- Strong La Niña conditions typically enhance monsoon rainfall over India by strengthening the Walker circulation.

- However, the concurrent nIOD exerted a counteracting influence, suppressing convection over the Indian subcontinent and preventing excessively high rainfall anomalies.

This compensation between Pacific and Indian Ocean drivers highlights the complexity of monsoon predictability and underscores the risks of relying on single-index indicators.

Why We Should Pay Attention

Multi-year climate anomalies such as the 2021–2022 nIOD are important because they can:

- Amplify or dampen seasonal weather extremes, including droughts and floods

- Affect food security, water resources, and disaster risk

- Reveal critical dynamics in ocean–atmosphere coupling that challenge existing prediction models

Emerging research suggests that multi-year La Niña events may become more frequent in a warming climate, with important implications for the Indian Ocean:

- Persistent La Niña conditions may favor prolonged westerly wind anomalies over the equatorial Indian Ocean

- These winds increase the likelihood of sustained negative IOD conditions, including multi-year events

- The Indian Ocean may increasingly exhibit Pacific-forced memory, reducing its tendency to reset seasonally

In this context, the 2021–2022 multi-year nIOD may not represent an isolated anomaly, but rather a precursor of future climate behaviour under continued global warming.