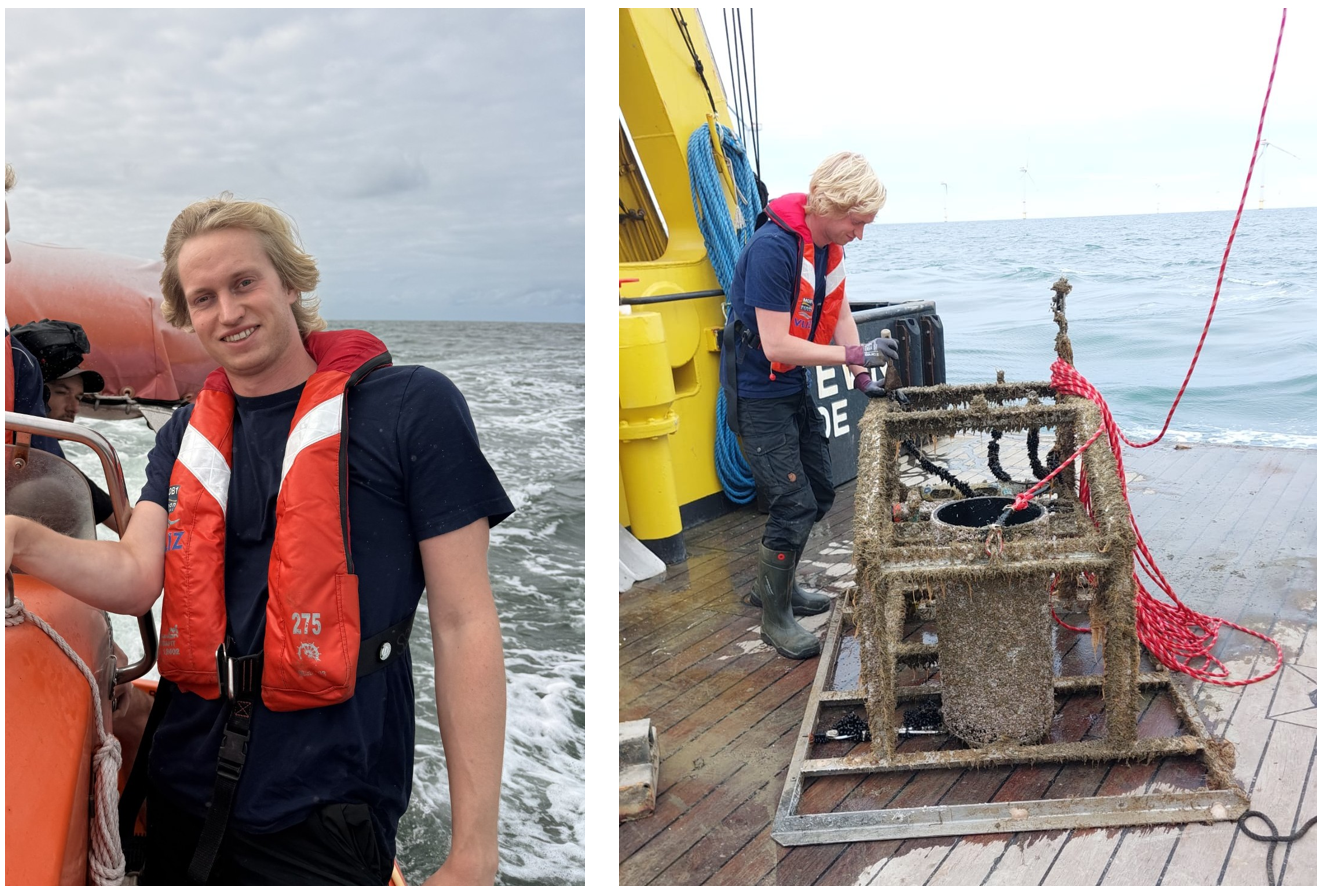

We chatted with Bram Cuyx, an underwater acoustics AI research engineer at the Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ) in Belgium, about his unique path from engineering into marine science. In this interview, he shares how he made the leap from signal processing in electronics to listening to the soundscape of the North Sea, what it’s like to build a sound library for AI, and why acoustics might be the key to better understanding and protecting marine ecosystems. Discover the challenges, surprises, and future ambitions behind the Marine SoundLib project — and why open data and collaboration are essential to advancing ocean science in the age of AI!

🌊What sparked your interest in marine science, and how did you end up working on underwater sound?

I’m actually new to marine sciences — this is my first year in the field. My background is in electronics engineering, with a focus on signal processing, especially acoustics. I’ve always looked for projects with meaningful impact, often at the intersection of engineering and life sciences. I came across this job at VLIZ quite randomly — a university colleague sent it to me. I was immediately drawn to the project. It felt like a natural continuation of my work: collecting sound data, labelling it, and analysing it to uncover patterns.

🌊How would you explain your current project — building an underwater sound library for AI — to a general ocean audience?

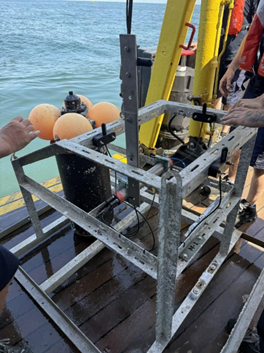

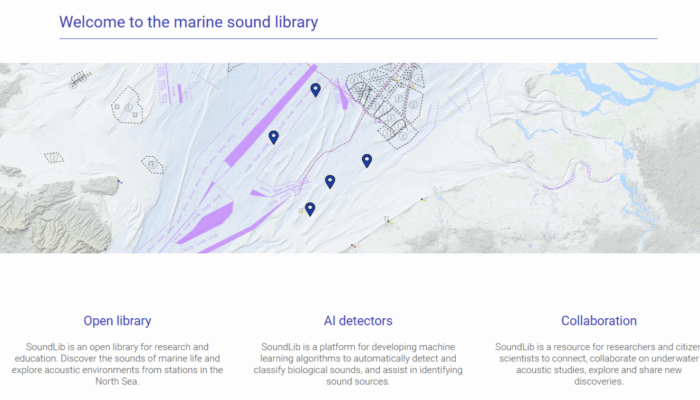

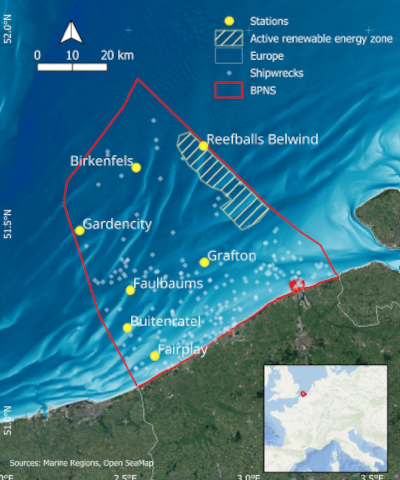

We recently launched Marine SoundLib, a platform where researchers, policymakers, and anyone with a love for the ocean can explore the underwater sounds of the North Sea. Using passive acoustic monitoring, we deploy hydrophones on moorings for months at a time, letting them quietly “listen” to everything happening beneath the surface. After recovering the instruments, we analyse the full underwater soundscape—from waves and wildlife to vessels passing in the distance. Want to dive into the North Sea without getting wet? Put on your headphones and explore the sounds here.

Collecting and processing this data demands substantial resources, including ships, technical expertise, and computing power. To address this, Marine SoundLib makes the data openly accessible, enabling researchers without such resources to study and better understand the underwater environment. We provide access to curated datasets, often labelled by sound source, allowing researchers to train AI models and perform their own analyses. Additionally, we encourage other institutions to contribute data under a shared protocol, building a collaborative resource. By sharing these insights with the public and policymakers, we aim to raise awareness of underwater noise pollution and support informed marine planning to protect ocean ecosystems.

Image: Stations of LifeWatch Broadband Acoustic Network in the Belgian Part of the North Sea (BPNS).

🌊How challenging is it to distinguish between human-made sounds and natural sounds underwater? What methods do you use to differentiate and handle them?

Distinguishing human-made from natural underwater sounds is quite challenging and requires significant manual effort. We typically start by manually labelling recorded sounds. Sometimes, labelling can be done automatically when we know specific activities are happening—for example, using satellite data to track ship movements near our hydrophones or knowing when pile driving occurs during wind farm construction.

Labelling biological sounds, like those from fish, is much harder. That’s why our platform is valuable: it lets researchers compare sounds and use clustering algorithms that group similar sounds together. Soon, users will be able to upload unknown sounds, see which cluster they fit into, and help verify or correct labels. By combining expertise from multiple institutions through this collaborative approach, we improve the accuracy of sound identification and deepen our understanding of the underwater soundscape.

🌊Why do you think this kind of research is important? What are some of the key questions you’re trying to answer?

Unlike many traditional monitoring techniques, underwater acoustic monitoring is minimally invasive and especially effective in turbid environments like the North Sea, where visual tools such as cameras are limited. Because sound travels much farther in water than in air, it enables us to monitor large areas using relatively few sensors.

Our goal is to use sound to better understand the structure and health of marine ecosystems: which species produce which sounds, how they use them for communication or navigation, and how these natural behaviours may be disrupted by increasing human activity. Despite growing pressure from shipping, construction, and resource extraction, we still know surprisingly little about the effects of underwater noise pollution on marine life. This is an urgent and open research question. By listening more closely, we aim to detect early signs of ecosystem change and gain insights into how human-generated sound may be altering the evolution and balance of ocean life.

🌊Have you already found any interesting or unexpected results from the SoundLib work so far? (maybe a surprising or memorable underwater sound in your work that you would like to share?)

Absolutely — stepping into this field was already a fascinating experience. Just listening to the underwater soundscape for the first time was memorable in itself.

One of the most surprising sounds we’ve come across is something we call the metallic bell. It’s a sharp, bell‑like ringing sound that, at first, doesn’t seem natural at all. But we suspect it’s actually produced by a crab using its pincers — which makes it even more fascinating. This particular sound was recorded during the PhD work of Clea Parcerisas. Hearing such a perfectly metallic tone underwater, likely from a biological source, really sticks with you.

Another exciting development is the similarity plot we’re building into the Marine SoundLib platform. It allows users to explore how different underwater sounds cluster together using machine learning. Soon, people will be able to upload their own sounds, compare them with existing data, and see where they fit. It’s a powerful tool for discovery — and we’re excited to open it up to the wider research community.

🌊And lastly, if you could record the sound of any place in the ocean, where would it be—and why?

I would love to be able to record sounds in less sampled areas. Sampling density in locations in the global south is much lower, but these are just as important to global biodiversity. If we live by the principles of one ocean putting resources towards monitoring these areas should be a given.