Mesoscale eddies and Southern Ocean carbon sink

The Southern Ocean takes up more than a quarter of the anthropogenic CO₂. Its powerful westerly winds, deep overturning circulation, and intense mixing make it a major player in Earth’s climate system. But beneath this large-scale picture lies a world of swirling, dynamic structures that constantly reshape the ocean’s physical and biogeochemical properties: mesoscale eddies.

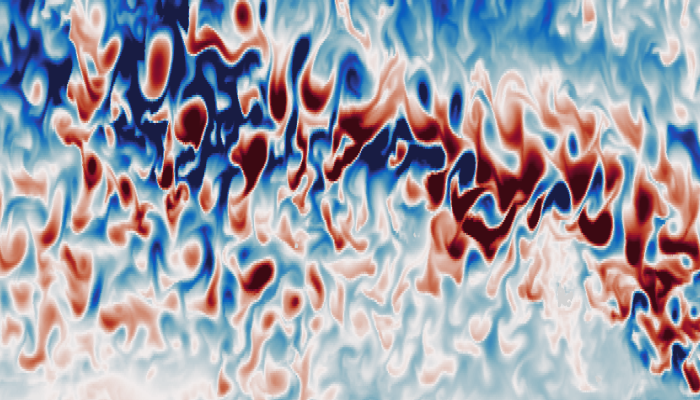

Cyclonic and anticyclonic mesoscale eddies— rotating features with spatial scales of 10–200 km— are far more than background turbulence. They trap and transport water masses, alter nutrient pathways, and modulate air-sea gas exchange. Yet their contribution to the Southern Ocean carbon sink has remained difficult to quantify, especially over longer timescales.

Zooming in: The challenge of studying high-latitude eddies

Although oceanographers have known for decades that the Southern Ocean is rich in mesoscale activity, quantifying the impact of eddies on CO₂ fluxes is challenging. As we move toward higher latitudes, the Rossby radius of deformation decreases, meaning that eddies become smaller. Instead of the large (100–200 km) vortices typical of subtropical regions, Southern Ocean eddies often span only a few tens of kilometres.

This reduction in scale makes them challenging to study: high-latitude measurements are sparse and high-frequency sampling is needed to capture eddies. At the same time, many global climate models lack the spatial resolution required to explicitly represent mesoscale eddies at higher latitudes. As a result, much remains unknown about how these mesoscale processes influence the carbon cycle.

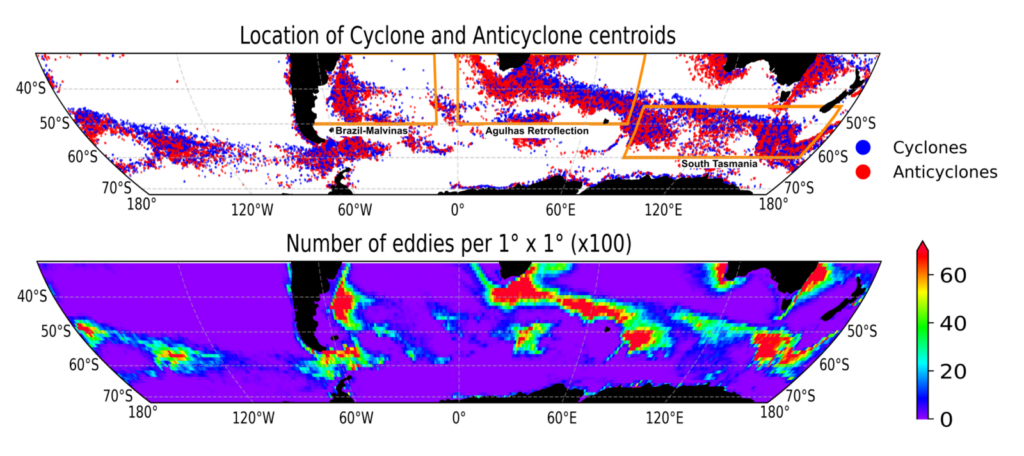

Figure 1: Locations of detected anticyclonic and cyclonic eddy centroids in our simulation, the defined regions (orange rectangles), and the eddy centroid counts within 1° × 1° grid cells.

Why cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies might influence CO₂ fluxes differently

Cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies are not just oppositely rotating features, they create fundamentally different physical and biogeochemical environments that can alter the exchange of CO₂ between the ocean and the atmosphere. Anticyclonic eddies (clockwise rotation in the Southern Hemisphere) are typically associated with downwelling. This downward movement of water can transport carbon from the surface to deeper layers, effectively helping the ocean carbon uptake. However, this physical structure also has side effects that complicate their role. Downwelling suppresses the upward supply of nutrients and deepens the mixed layer, which can limit primary production. Additionally, higher surface temperatures decrease CO₂ solubility. In contrast, cyclonic eddies, which are typically associated with upwelling, have the opposite effects.

Mesoscale eddies heterogeneously modulate CO₂fluxes in eddy-rich regions of the Southern Ocean

In our recent study (Salinas-Matus et al., 2025), we examined how eddies influence the air-sea CO₂ flux in the eddy-rich regions of the Southern Ocean. We carried out a relatively long simulation for this type of high-resolution ocean–biogeochemical model: a 27-year global run. We distinguished different dynamical environments—cyclonic eddies, anticyclonic eddies, eddy peripheries, and background waters. We were able to examine how CO₂ fluxes, vary across eddy types and how these effects evolve from daily to decadal timescales. Our analysis reveals these results:

1. Eddy impacts vary widely across the Southern Ocean

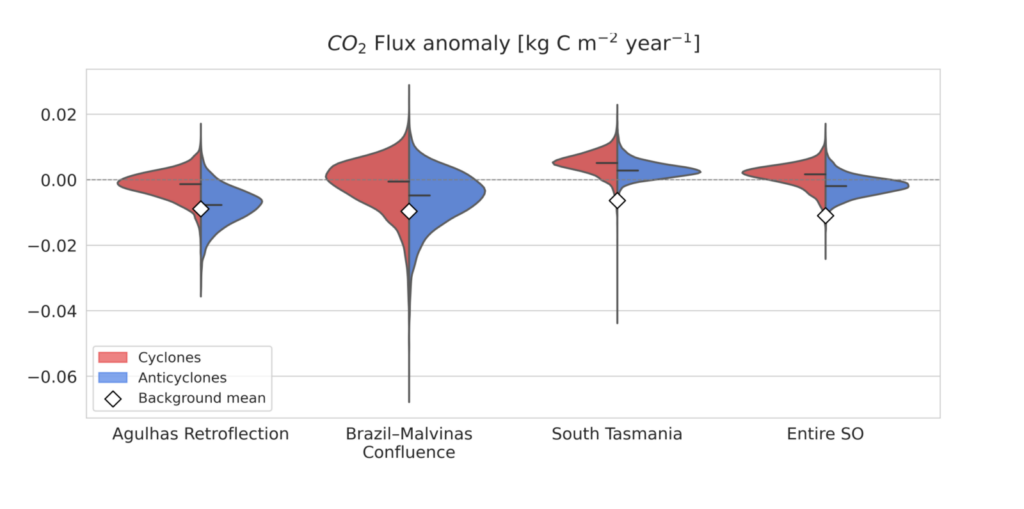

Eddies do not exert a uniform influence on air–sea CO₂ exchange. Their effects depend strongly on the geographic region, eddy polarity (cyclonic vs. anticyclonic), and the surrounding circulation. This spatial heterogeneity highlights the importance of resolving mesoscale processes when assessing regional carbon fluxes.

2. Anticyclonic eddies are more efficient at taking up CO₂

Overall, anticyclones exhibit a stronger efficiency to absorb atmospheric CO₂. Their downwelling-favourable structure enhances CO₂ uptake by transporting surface waters downward and maintaining lower surface DIC concentrations. Cyclones and eddy peripheries also contribute, but their efficiency is generally weaker.

3. Over decadal scales, eddies consistently absorb CO₂

Although eddy-driven CO₂ fluxes show substantial variability on daily and seasonal timescales, their long-term imprint is robust: eddies act as persistent carbon sinks across all regions examined. This suggests that mesoscale processes, despite being patchy in space and time, help support the long-term carbon-sink behaviour of the Southern Ocean.

4. Yet their overall contribution remains modest

Despite strong local effects, the total contribution of eddies to CO₂ uptake is relatively small— about 10% of the Southern Ocean’s total uptake and roughly 1% of the anomalous uptake.

Overall, these findings underscore a heterogeneous—but non-negligible—role for mesoscale eddies in shaping the Southern Ocean carbon budget.

Figure 2: Composite anomalies of total CO₂ flux relative to the “background” for anticyclonic and cyclonic eddies in the regions defined in Figure 1.

Why this matters

This matters because understanding the Southern Ocean is like trying to read a book where some of the letters are too small to see. When we resolve the finer print we gain a more complete story. Our findings don’t rewrite the role of the Southern Ocean in the global carbon cycle, but they add an important chapter that helps explain how this critical region functions. In short, if we want to understand how the ocean takes up carbon, we need to pay attention not only to the big currents and large-scale patterns but also to the small swirling structures that quietly shape them.