As climate change continues to reshape our oceans, science communication remains vital to the research and development of mitigation strategies. For scientists and engineers working on climate solutions, much of the conversation happens through technical papers, conference presentations, and policy memos. But invested communities outside these circles may have little access and limited time to consume such products, instead sharing information by word of mouth and social media.

Closing this communication gap between scientists and communities is imperative for the fast-evolving field of marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR). As governments worldwide invest in mCDR methods that aim to use the ocean to lock away carbon from the atmosphere, people who live, work, and depend on the ocean want to have a voice in decisions to advance mCDR research.

That’s why we created “A Fisherman’s Guide to Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal”, a communication tool designed to support ongoing dialogue between ocean-dependent communities, policymakers, and researchers.

What is mCDR and why should fisheries care?

Marine carbon dioxide removal is a set of proposed methods that leverage the ocean’s natural processes to remove carbon from the atmosphere and store it in the ocean for at least a thousand years. A portfolio of strategies is needed for reaching net-zero carbon emission targets to mitigate climate change, but strategies like mCDR are also necessary to remove carbon that was emitted in the past.

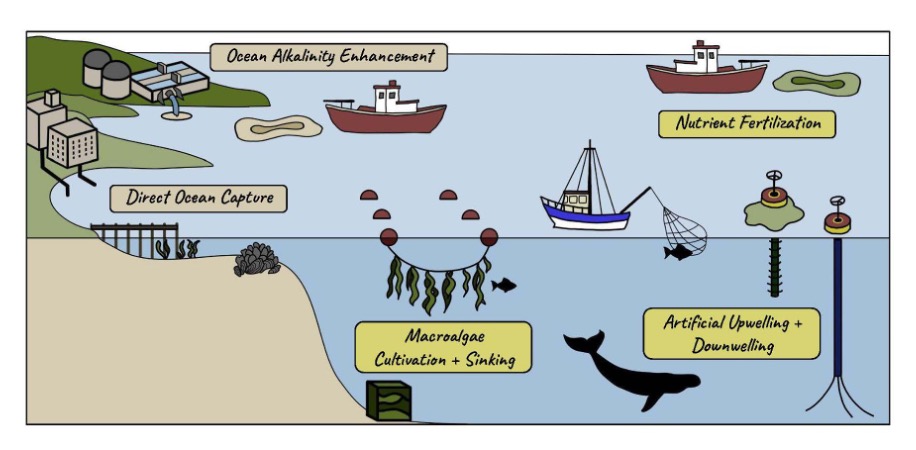

mCDR methods fall into two broad categories:

- Abiotic approaches enhance the ocean’s natural ability to absorb CO₂. This can involve adding alkaline minerals to seawater, or using technology to strip carbon from the ocean so more carbon can be absorbed.

- Biotic approaches rely on photosynthesis to capture carbon from the atmosphere (think seaweed cultivation or phytoplankton growth). For biotic approaches to work as carbon removal strategies, the biomass needs to be sunk to the deep ocean to keep the stored carbon out of the atmosphere.

Image: Illustration of abiotic mCDR approaches (ocean alkalinity enhancement, direct ocean capture) and biotic mCDR approaches (nutrient fertilization, macroalgae cultivation and sinking, artificial upwelling, and artificial downwelling) deployed in the coastal and open ocean. Illustration created by: Madison Wood.

These interventions may bring benefits for the ocean and ocean-users, such as reducing local ocean acidification or expanding fish habitat. They could also introduce new challenges. Adding nutrients might disrupt local food webs. Sinking biomass could reduce oxygen levels in deeper waters. Increased ship traffic or marine infrastructure might affect fishing activity.

The overlap is clear: fisheries and mCDR share ocean space, ecological systems, and often regulatory frameworks. As mCDR research efforts accelerate, fisheries communities and mCDR practitioners must share productive conversations about potential trade-offs and opportunities.

The value in tailoring information to key audiences

While conversations about mCDR in the research and fishing communities may often happen in different circles, there are many reasons to foster this kind of cross-sector dialogue early on. For one, fisheries and aquaculture practitioners have invaluable ecological knowledge and long-term experience with monitoring, permitting, and adaptation. Their input can shape mCDR designs that avoid sensitive areas, minimize unintended consequences, and enhance co-benefits like acidification buffering or ecosystem restoration.

Image: Photograph of fishing boats with nets in the Caribbean. Image Credit: Hugh Whyte / Ocean Image Bank

However, dialogue only works if the communication tools and decision-making processes are accessible. That means simplifying scientific jargon, contextualizing potential trade-offs, and building trust through clear, ongoing engagement.

Tailored materials, like the one-page explainer we share here, aim to make mCDR more accessible. Rather than distilling every scientific detail, the goal is to offer a useful overview that centers the information the fishery and aquaculture communities need. When people have information in formats and language that make sense for their work, they’re better equipped to ask questions, contribute insights, and get involved early in decision-making.

mCDR is no longer just a concept. It is being tested and shaped in real time. In the last few years alone:

- National research agencies in the US, EU, and Germany have invested millions into understanding the risks and potential of different mCDR methods, with programs including SEA-CO2 (US), NOAA NOPP (US), and CDRmare (Germany).

- Startup companies and researchers alike are leading pilot projects under existing environmental regulations

- Policymakers nationally and internationally are communicating on the governance systems that will allow for in water work

The growth of the mCDR field must be guided by coastal communities, especially those with deep experience managing ocean resources. To do so efficiently requires paving the pathways for these voices to participate meaningfully.

We want your feedback!

This mCDR explainer for fishermen is just a starting point. We hope it sparks questions, conversation, and constructive critique. What additional information should be included? Are there diagrams or analogies that would make these ideas more intuitive? Would you like to see this translated, adapted to local species or practices, or offered in other formats?

Whether you’re a fisherman, scientist, policy advisor, or organizer, your input can help shape how this complex topic is communicated and understood.

Click here to view the one-pager.

Let us know what you think by reaching out to mamwood@ucsc.edu

Disclaimer

The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Department of Commerce, or the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Andy Dale

Hi there,

An overlooked side issue with trawling is the impact of buried reduced sulfur compounds (e.g. pyrite, FeS2) being exposed to oxygen after trawling and then releasing O2 to the atmosphere after they are oxidized in the water.

Please see our lab and field experiments in the following open access papers that were the first to demonstrate the potential impact of pyrite oxidation by trawling on marine CDR:

https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-2905

https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02132-4