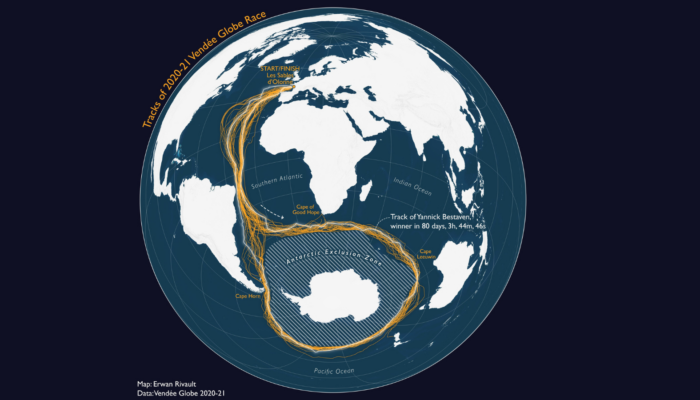

The Vendée Globe began on November 10th, with 44 participants embarking on the world’s toughest sailing race. This non-stop, single-handed round-the-world yacht race challenges skippers to circumnavigate the Southern Ocean. The race starts in France, traverses the North Atlantic, and heads directly into the Southern Ocean. Despite taking place during the austral summer, the conditions remain extreme, with waves reaching towering heights. In the previous race, the 2020/21 Vendée Globe, a skipper was forced to abandon his sinking yacht after it broke in two in the Southern Ocean. Participants took between 80 to 116 days to complete the journey. With the ocean as their second home, these skippers advocate for ocean conservation, raise awareness for ocean protection, and inspire climate action. However, during this yacht race skippers are not just competing—they are collecting valuable data, particularly in the Southern Ocean. This data is crucial for understanding the ocean’s role in climate change.

Landschützer et al., 2023 highlight sailboats as a unique opportunity to observe remote ocean regions such as the Southern Ocean, where limited data coverage leads to large uncertainties when reconstructing the air-sea CO2 flux. Skippers collect critical data while sailing through algae blooms, eddies, storms, and frontal zones. In the Vendée Globe race, skippers carry a variety of scientific instruments: they will deploy Argo floats and weather buoys, carry a plankton imaging platform, measure atmospheric aerosols and the partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2), and more.

Among the 25 skippers advancing ocean science and observations, 4 are measuring pCO2. In the last Vendée Globe, Boris Herrmann became the sole skipper measuring sea surface pCO2 with his yacht “Seaexplorer – Yacht Club de Monaco” after Fabrice Amedeo had to retire from the race due to problems with the main computer just before entering the Southern Ocean. But how does the collected data shape our understanding of the ocean carbon cycle? Can a single sailboat make a difference in estimating how much carbon the ocean absorbs?

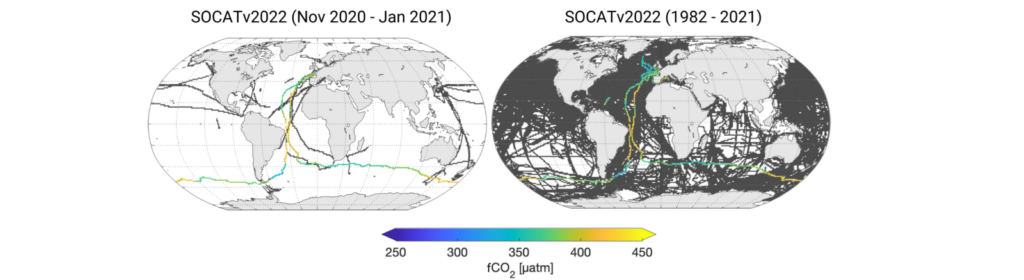

Figure 1: Data availability in the SOCATv2022 database across different time periods. Colored lines represent the sailboat tracks used in Behncke et al., 2024, while other data measured by ships, buoys, autonomous measurement platforms etc. is shown in grey.

It turns out, that in the underobserved Southern Ocean, pCO2 data measured by a single sailboat significantly changes the estimate of the ocean carbon sink. Behncke et al., 2024 show that even one sailboat (“Seaexplorer – Yacht Club de Monaco” with skipper Boris Herrmann measuring during the last Vendée Globe 2020/21) makes a difference in estimating the ocean carbon sink.

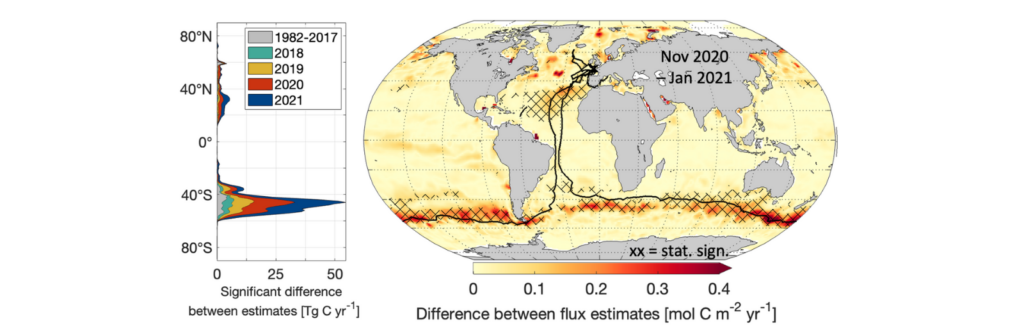

Since 2018, the sailboat “Seaexplorer – Yacht Club de Monaco” has collected > 250 000 pCO2 measurements data for 129 days (2018–2021), including an Antarctic circumnavigation – the Vendée Globe 2020/21. Behncke et al., 2024 show that these observations significantly change the estimate of the ocean carbon sink in the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean. The new sailboat observations significantly increase the estimate of the regional carbon uptake in the North Atlantic and decrease it in the Southern Ocean. These compensating changes in both basins limit the global effect. The Southern Ocean, particularly between 40°S and 60°S, exhibited the largest air-sea CO2 flux changes, averaging 20% of the regional mean. The highest impact occurred during summertime, reflecting the seasonal availability of the data from the circumnavigation race (Nov 2020 – Jan 2021). Additionally, the impact was largest in regions where the sailboat crossed the frontal zones in the Southern Ocean, regions known for their complex biogeochemical processes. The results stay robust within a measurement uncertainty of ± 5 μatm but become undetectable with a measurement offset of 5 µatm.

Figure 2: Difference between the air-sea CO2 flux estimates based on pCO2 observations in SOCATv2022 including sailboat data and excluding sailboat data between November 2020 and January 2021. The black line represents the sailboat tracks. (modified after Behncke et al., 2024)

Behncke et al., 2024 conclude that sailboats fill essential measurement gaps in remote ocean regions and should serve as a complementary observing platform to research vessels and robotic floats – especially in light of the alarming decline in ocean CO2 observations. Sailboats hold the potential to improve reconstructive air-sea CO2 flux estimates on a larger scale in the future.

References:

-

- Press Release: The IMOCA sailors – key contributors to global oceanographic science

- Landschützer P, Tanhua T, Behncke J, Keppler L. 2023 Sailing through the southern seas of air–sea CO2 flux uncertainty. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 381: 20220064. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2022.006

- Behncke, J., Landschützer, P. & Tanhua, T. A detectable change in the air-sea CO2 flux estimate from sailboat measurements. Sci Rep 14, 3345 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53159-0