Today, 1st December 2017, marks the 58th anniversary of the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959. The Antarctic Treaty was motivated by international collaboration in Antarctica in the International Geophysical Year (IGY), 1957-1958. During the IGY over 50 new bases were established in and around Antarctica by 12 nations- including this one at Halley Bay which was maintained for over a decade before being replaced. These nations signed the Treaty to keep Antarctica as a continent of peace and scientific research. Since 2010, this date has been marked by Antarctica Day, which is used to promote awareness of Antarctica as an international space with benefits for all.

Antarctica as a continent of peace and scientific collaboration

In the year 1957-1958, 67 countries participated in the International Geophysical Year (IGY). This was (a bit confusingly) 18 months of international coordinated observations and data retrieval. The goal was to exploit new tools and techniques to advance science in a huge range of geophysical disciplines. The results, direct and indirect, were widespread. For example it is no coincidence that the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched by the USSR in October 1957, after the USA had announced they would launch a satellite as part of IGY activities.

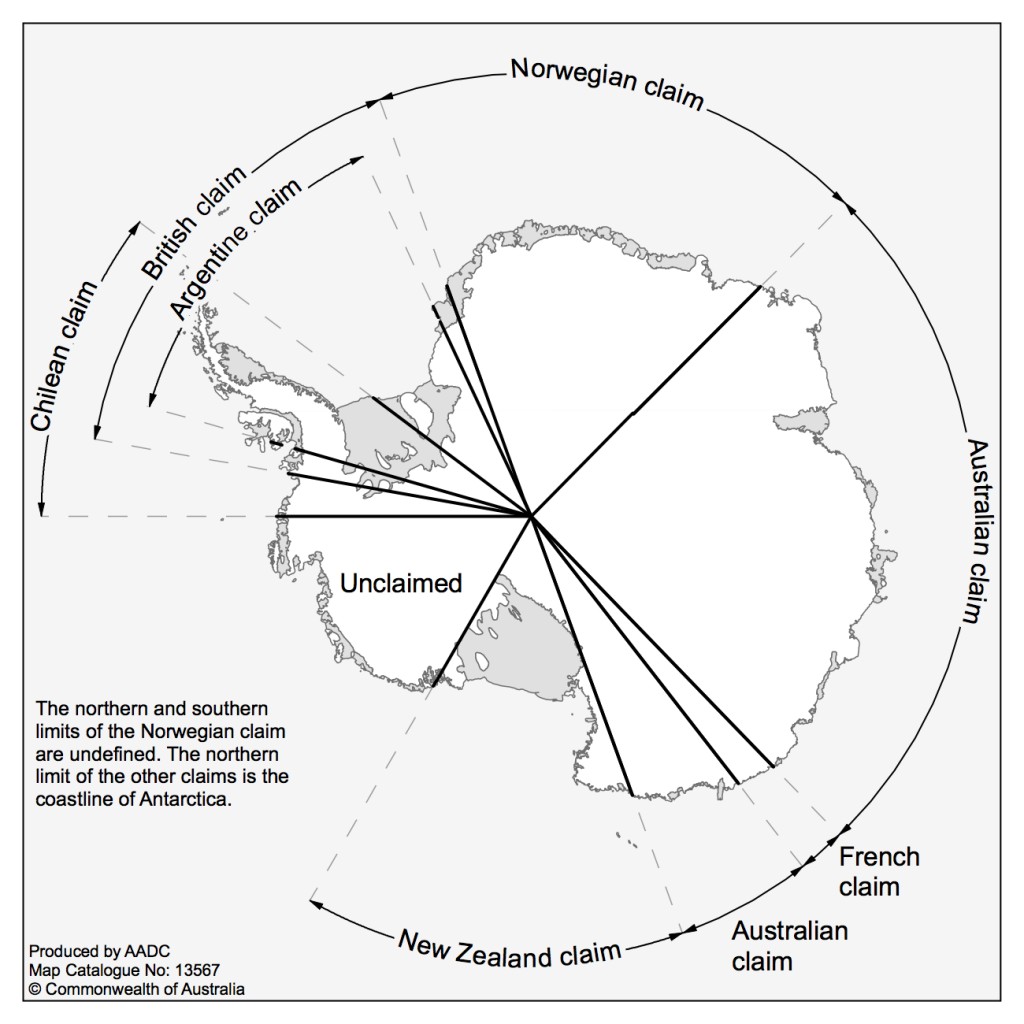

Fig.2: Territorial claims in Antarctica [Credit: Australian Antarctic Data Centre ]

Expeditions in Antarctica were a major activity of the IGY. Seven countries had territorial claims in Antarctica at the time, some of them overlapping (Fig. 2). To make sure that territorial disputes did not hinder scientific progress, it was established that these political goals for Antarctica would be set aside during the IGY, and scientific goals prioritized. As a result, 12 countries operated around Antarctica during the IGY: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, United Kingdom, United States and USSR. This included those with previous claims as well as those like the USA and USSR who had not previously had activities in Antarctica.

Out of concern for maintaining the scientific legacy of this fantastic year of collaboration, these same 12 countries gathered in 1959 for the “Conference on the Antarctic” in Washington D.C.

The original Treaty had two main components:

- Antarctica should be used for ‘peaceful means only’. It would not be permitted to establish military bases, carry out military maneuvers, or test weapons.

- There should be ‘freedom of scientific investigation’. In particular, the Treaty laid out terms of collaboration, such that personnel, information about activities, and the results of scientific observations, should be shared freely.

The Antarctic Treaty covers the area from 60 to 90 degrees south, enclosing the entire Antarctic continent as well as many Antarctic islands and a large area of the Southern Ocean.

Future Treaties: Protecting the Environment

The Antarctic Treaty didn’t directly include protections for the environment. However, it did state that future meetings would consider actions related to the Treaty, including those ‘regarding preservation and conservation of living resources in Antarctica’. In the following decades, three major agreements were made to ensure the protection of different aspects of the Antarctic environment.

The first two were the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals, in 1972, and the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, in 1982.

The third is the ‘Environmental Protocol’ (full and lengthy name “The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty”). This wide-ranging protocol was signed in 1991 and came into force in 1998, and established the Committee for Environmental Protection. The overarching purpose of the protocol is a commitment “to the comprehensive protection of the Antarctic environment and dependent and associated ecosystems and hereby designate Antarctica as a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science“. It covers all activities in the Antarctic Treaty region, south of 60°S. It lays out reasons for protecting Antarctica – as a home to ecosystems, a unique wilderness, and as a crucial location for scientific research and for understanding the global environment. It outlines types of adverse impact to be avoided; for example, pollution, environmental change, damage to significant locations, and disruption of ecosystems by exploiting them or by introducing foreign species. And, the protocol establishes how such impacts are to be avoided, for example by requiring Environmental Impact Assessments before any activity is carried out.

Celebrating the Treaty: Antarctica Day

Inspired by 50 successful years of the Antarctic Treaty, Antarctica Day was launched on the 1st December 2010 and is celebrated on this date each year. Its goals are to celebrate the success of this international coordination treaty and the resulting international peaceful co-operation in Antarctica, raise awareness of the uniqueness of Antarctica, and to encourage conversation and collaboration between students, scientists and officials.

A number of particular activities take place each year. One is an ‘Antarctic flags’ event, organized by the Association of Polar Early Career Researchers (APECS), and currently managed by its UK branch, the UK Polar Network. School children design flags ready for Antarctica Day, which are then proudly displayed by researchers visiting Antarctica over the Antarctic summer (northern hemisphere winter!).

Fig.3: “Los niños de 5to año de la Escuela 163 “Japón” de La Paz- Uruguay”: Antarctica Day 2017 flags designed by school children in Uruguay. [credit: Valentina Cordoba. Provided by Sammie Buzzard.]

If you’re going to Antarctica in the next couple of months and can take a photo of yourself with one of the flags while there, please email education@polarnetwork.org

Happy Antarctica day!

Further Reading

- NOAA website about the International Geosphysical Year : https://celebrating200years.noaa.gov/magazine/igy/welcome.html

- IGY and the Antarctic Treaty | Encyclopedia Britannica

- How Antarctica became home to a new kind of scientific diplomacy | The Guardian

- The website of the Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty

- An image showing the signing of the Antarctic Treaty by the U.S. Representative. : http://atsimagebank.omeka.net/items/show/9

- Our spaces, Foundation for the Good Governance of International Spaces: https://www.ourspaces.org.uk/antarctica-day.html

- The Antarctic Treaty (English link, also available in Spanish, Russian and French)

- The Environmental Protocol (English link, also available in Spanish, Russian and French)

Edited by Sophie Berger

Caroline Holmes is a postdoctoral researcher at the British Antarctic Survey, UK. She investigates how well sea ice is represented in coupled climate models. The climate models used to project the evolution of the earth system under climate change represent very differing behaviors in terms of the seasonal cycle of sea ice cover at each pole, and trends in the recent past and projected future. Caroline’s work seeks to understand these differing behaviors by examining sea ice processes and atmosphere-ocean-ice linkages. Twitter @CHolmesClimate. Contact Email: calmes@bas.ac.uk

Caroline Holmes is a postdoctoral researcher at the British Antarctic Survey, UK. She investigates how well sea ice is represented in coupled climate models. The climate models used to project the evolution of the earth system under climate change represent very differing behaviors in terms of the seasonal cycle of sea ice cover at each pole, and trends in the recent past and projected future. Caroline’s work seeks to understand these differing behaviors by examining sea ice processes and atmosphere-ocean-ice linkages. Twitter @CHolmesClimate. Contact Email: calmes@bas.ac.uk