Have you ever wondered how many glaciers will still exist in the future? Or how many glaciers we might lose each year in the coming decades? In our new study (Van Tricht et al., 2025), we shift the focus of glacier modelling from ice volume to individual glaciers. Because every glacier, no matter how small, can matter. Not necessarily for global sea-level rise, but for landscapes, ecosystems, cultures, and communities. Using three independent glacier models, we simulated the future of each of the world’s nearly 200,000 glaciers, asking a simple but powerful question: when will each glacier disappear?

Why every individual glacier matters

Most people know that glaciers contribute to global sea-level rise. Currently about 1 mm per year comes from melting glacier ice (The Glambie Team, 2025). Glaciers are also vital freshwater sources, especially in dry regions such as the Andes or Central Asia, where meltwater keeps rivers flowing during hot summer months. But glaciers are more than water towers or ice reservoirs. Large and small glaciers can have touristic, economic, cultural, and even spiritual value (Allison, 2015; Barton and Goh, 2025). Think of glacier ski areas, ice caves, classic alpine routes across ice (e.g., Eiger West Face, Margreth et al., 2017), or the myths and legends tied to glaciers. Climate change threatens all of this. Imagine a remote Alpine valley with a small glacier at its head. That glacier barely matters for sea-level rise and only little for water supply. But for the local community, who have seen the ice from their windows for generations, and who welcome summer visitors coming to “see the glacier”, its value is enormous (Salim, 2026). Possibly far greater than that of a very large glacier located far from any community. The emotional importance of glaciers becomes clear in the growing number of “glacier funerals” held around the world, where glaciologists, local residents, and religious leaders gather to remember the disappearance of “their” glacier (Huss et al., 2025). That is why, in this study, we set out to determine the year of disappearance (extinction year) for every individual glacier on Earth

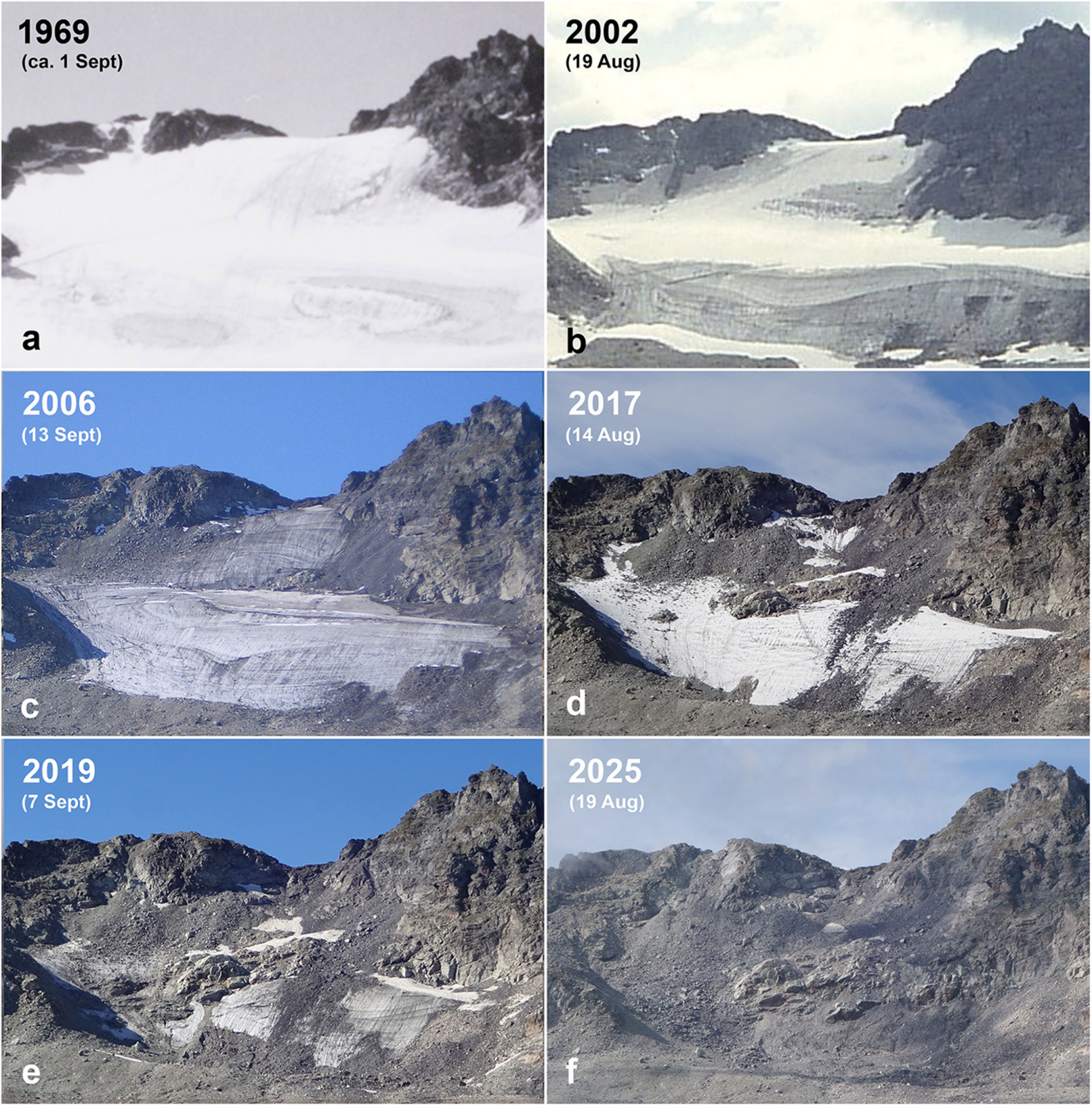

Fig. 2: Pizolgletscher in the Swiss Alps was already a very small glacier when the monitoring started 130 years ago. The glacier has become so small that it is considered extinct since 2022. Images were taken in August or September. Nowadays, tine ice patches remain below a thick layer of debris. More than 150 glaciers completely disappeared in Switzerland between 2016 and 2023. [Credit: U. Eugster, M. Huss, Huss et al., 2025]

When does a glacier officially disappear

This brings us to a key question: what exactly does it mean for a glacier to be “gone”? There is no single perfect definition, so in our study we used two simple and transparent criteria. A glacier is considered extinct when it becomes smaller than 0.01 km² in area, or 1% of its original ice volume. When either of these thresholds is crossed, we define that year as the glacier’s extinction year. You might wonder, what if a glacier splits into several smaller pieces? That does happen indeed. But because all three glacier models we use (OGGM, PyGEM, and GloGEM) are flowline-based models, i.e., they squeeze all the ice of a glacier in one central flowline, we consistently track all ice within the original glacier outline as defined around the year 2000. All remaining ice inside that outline is summed and compared to the extinction thresholds. In practice, this means we simulated every glacier in the Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI v6.0) under four global warming scenarios: +1.5 °C +2.0 °C +2.7 °C +4.0 °C global mean warming by 2100. These scenarios roughly span the range from strong climate mitigation consistent with the Paris Agreement (+1.5 °C), through intermediate pathways reflecting partial implementation of current national climate pledges (NDCs; ~+2.0 to +2.7°C), to a high-emissions future in which current global emissions continue largely unabated (+4.0°C). For a broader synthesis of the implications of these warming levels for glaciers and the cryosphere, see the ICCI State of the Cryosphere Report. For each glacier, and for each scenario, we now know when it disappears.

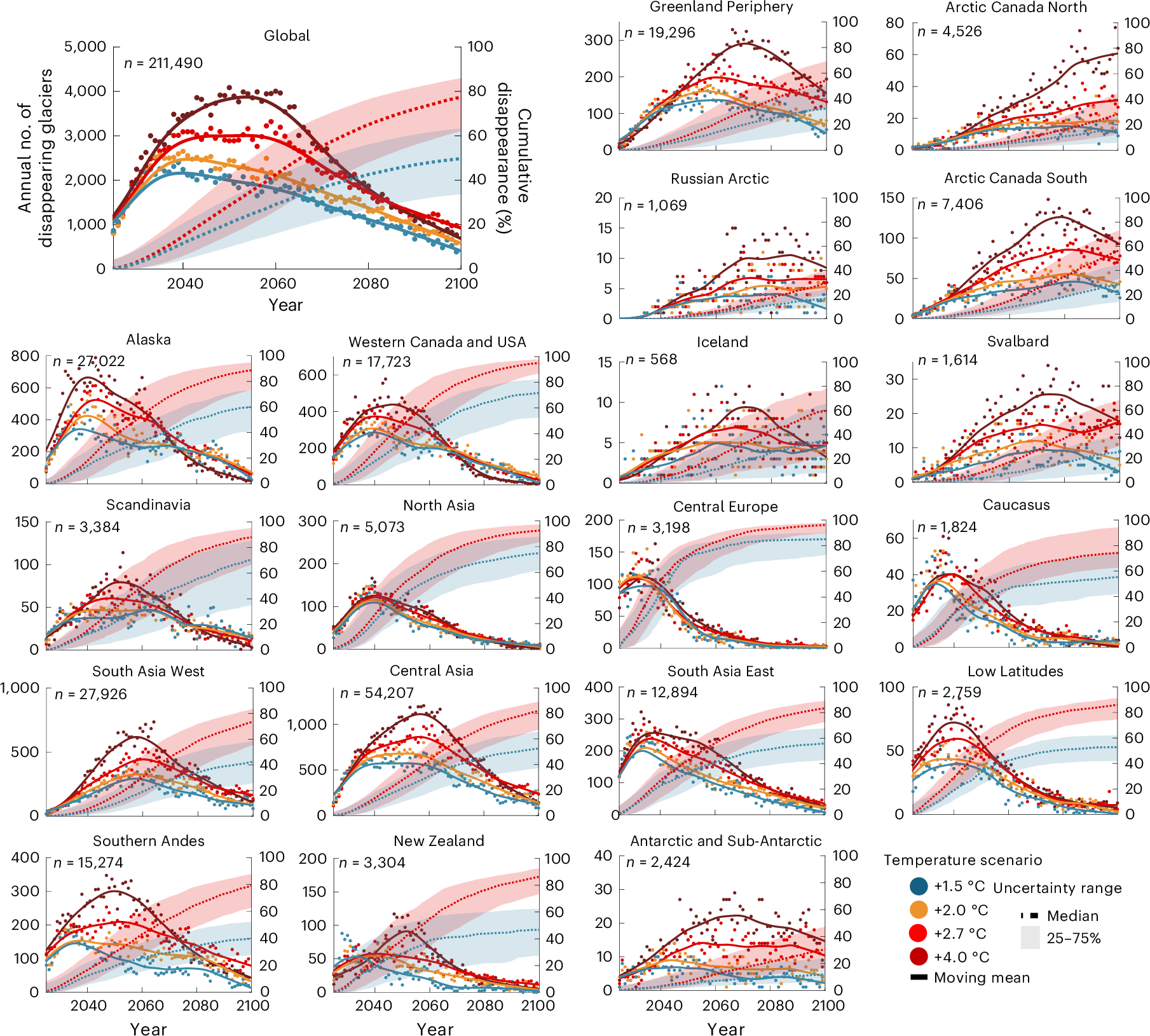

Global glacier loss peaks between 2040 and 2050

With these results, we can look at the big picture. When we count how many glaciers disappear each year globally, a striking pattern emerges. Glacier extinction peaks in the mid-21st century, roughly between 2035 and 2060. How high that peak becomes depends on future warming. Around 2,000 glaciers disappear globally per year if warming is limited to +1.5 °C. Around 3,000 glaciers per year under +2.7 °C. Up to 4,000 glaciers per year around 2050 under +4.0 °C warming. For comparison, today, we already lose about 850 glaciers per year. Losing 3,000 glaciers annually is equivalent to losing all glaciers in the Alps every single year. That is unprecedented. Looking further ahead to the year 2100, about 96,000 glaciers remain under +1.5 °C. About 78,000 under +2.0 °C. About 44,000 under +2.7 °C. Only 18,000 glaciers under +4.0 °C. As such, the message is clear: every fraction of a degree matters if we want to save our glaciers. The same conclusion applies to ice volume. Recent work by Zekollari et al. (2025) estimates that each additional 0.1°C of global warming commits roughly 2% of the remaining global glacier ice volume to loss.

Fig. 4: Number of glaciers lost each year (points, values on the left y axis). The solid lines represent 11-year running means. The dotted lines indicate the cumulative percentage of glaciers lost since 2025, with shaded bands showing the interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles) (values on the right y axis). n indicates the total number of glaciers in 2025. [Credit: Van Tricht et al., 2025]

Regionally, the situation is even more dramatic

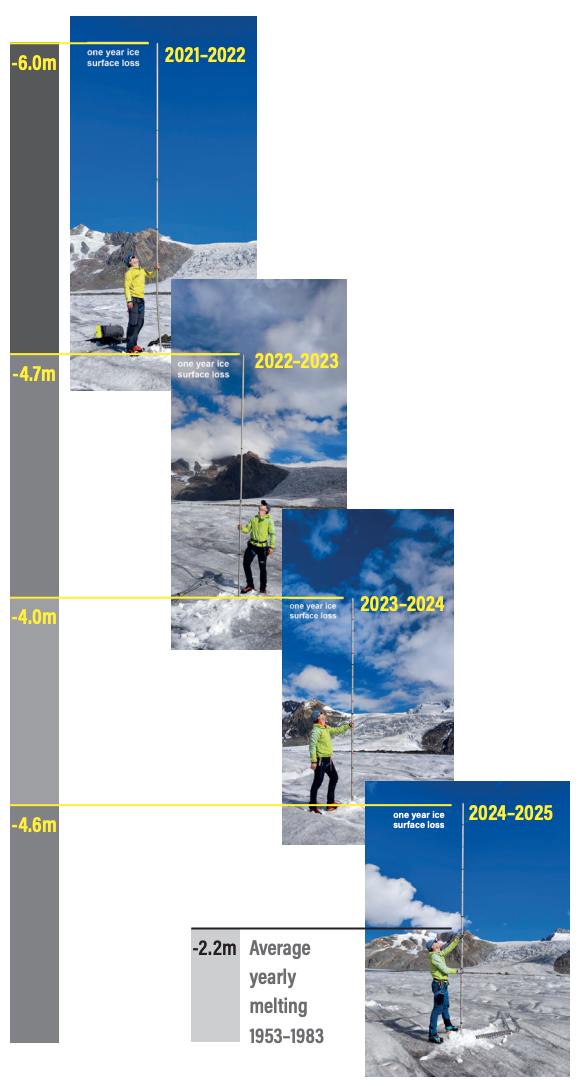

Global numbers already look alarming. But at the regional scale, the picture becomes even more stark. Take the European Alps. Today, they host roughly 3,000 glaciers, most of them small and with little capacity to survive repeated years of strongly negative mass balance. The summers of 2022 and 2023 alone removed about 10% of Swiss glacier volume in just two years (GLAMOS, 2023). Our projections show that even under the +1.5 °C scenario, the Alps loose 87% of their glaciers, leaving only ~400. Under +2.7 °C, only about 110 glaciers remain (8% of today’s number). Under +4.0 °C, just ~20 glaciers survive, confined to the highest peaks and often barely accessible or visible. The peak in glacier extinction in the Alps occurs within the next decade because of the many small glaciers that will disappear soon. Other regions, such as Western Canada and the United States, show similarly rapid losses. Regional impacts unfold much faster than the global average suggests.

Fig. 5: Ice loss at Konkordiaplatz, thickest ice of the Alps, Great Aletsch glacier, between 2022 and 2025 compared with the average measurements between 1953 and 1983. [Credit: Matthias Huss, Figure in ICCI State of the Cryosphere Report 2025]

What do we do with these results?

This study was developed in the context of the UN International Year of Glacier Preservation (2025) and the UN Decade of Action for Cryospheric Sciences (2025–2034), a period meant to raise awareness of the rapid changes happening in the world’s ice. Our results underline the urgency of ambitious climate policy:

Whether the world loses around 2,000 glaciers per year, still within reach under a rapid fossil fuel phase-out and net-zero emissions, or closer to 4,000 glaciers per year if current emission trends persist depends on choices made today. Every tenth of a degree of warming matters, not only for total ice volume, but for the survival of individual glaciers that shape landscapes, ecosystems, and human communities.

We also want to highlight that all results, at individual glacier scale and regional scale, are publicly available in an open repository. Anyone can look up when a specific glacier is projected to disappear under different warming scenarios. Explore the database or feel free to reach out, happy to take a look for your favorite glacier.

Fig. 6: The mighty Great Aletsch glacier, largest glacier in the Alps, will shrink to some small ice patches barely visible from the point of view by the end of the century. [Credit: Lander Van Tricht]

What about some iconic Alpine glaciers?

The repository enables users to identify the projected year of disappearance, or extinction, for every glacier worldwide. As an illustration, we present results for six iconic glaciers in the European Alps:

Great Aletsch Glacier (Switzerland)

- Disappears between 2084–2098 under +4 °C

- Survives under +1.5 °C, +2 °C, and +2.7 °C

Mer de Glace (France)

- ~50% chance of disappearing between 2094–2100 under +4 °C

- Survives under lower warming scenarios

Pasterze Glacier (Austria)

- Disappears 2061–2077 at +4 °C

- Only ~20% chance of disappearing before 2100 at +1.5 °C

Adamello Glacier (Italy)

- Disappears between 2053–2069 depending on warming level

Morteratsch Glacier (Switzerland)

- ~60% chance of disappearing before 2100 under +4 °C

- Survives under lower scenarios

Gorner Glacier (Switzerland)

- Survives even under +4 °C warming

Further Reading

- The Glambie Team (2025) Community estimate of global glacier mass changes from 2000 to 2023

- Allison (2015) The spiritual significance of glaciers in an age of climate change

- Barton and Goh (2025) Last chance tourism: A systematic literature review and future research directions

- Salim (2026) Mourning the death of glaciers: alpinists’ relationships with these more-than-human entities

- Huss et al. (2025) Monitoring the extinction of a glacier

- GLAMOS(2023) Two catastrophic years obliterate 10% of Swiss glacier volume

- Margreth (2017) Analysis of the hazard caused by ice avalanches from the hanging glacier on the Eiger west face

- Zekollari (2025) Glacier preservation doubled by limiting warming to 1.5°C versus 2.7°C

This blog post is associated with a recent publication in Nature Climate Change

- Van Tricht, L., Zekollari, H., Huss, M., Rounce, D. R., Schuster, L., Aguayo, R., Schmitt, P., Maussion, F., Tober, B., and Farinotti, D.: Peak glacier extinction in the mid-twenty-first century, Nat. Clim. Chang., 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02513-9, 2025.

- Van Tricht, L., Zekollari, H., Huss, M., Rounce, D. R., Schuster, L., Aguayo, R., Schmitt, P., Maussion, F., Tober, B., and Farinotti, D.: Peak glacier extinction in the mid-21st century, data and results. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17371641, 2025