As a child, Shakir remembers long extreme winters with heavy snowfall and dry blistering winds, where it was hard to play outside. He grew up in a village named Gulmit, located at an elevation of 2500 m, surrounded by the high snow caped mountains in the Karakoram Range in northern Pakistan. That was 30 years ago, when climate change was still not a cause of concern for the local people. Today, in the year 2020, he witnesses the change in the climate of this region. Now they have mild winters, hot and wet summers, shorter snowfall durations, earlier springs and irregular rainfall patterns during summer and winter. In today’s blog, Shakir Ahmed talks about his experience of climate change in his village in the Himalayas.

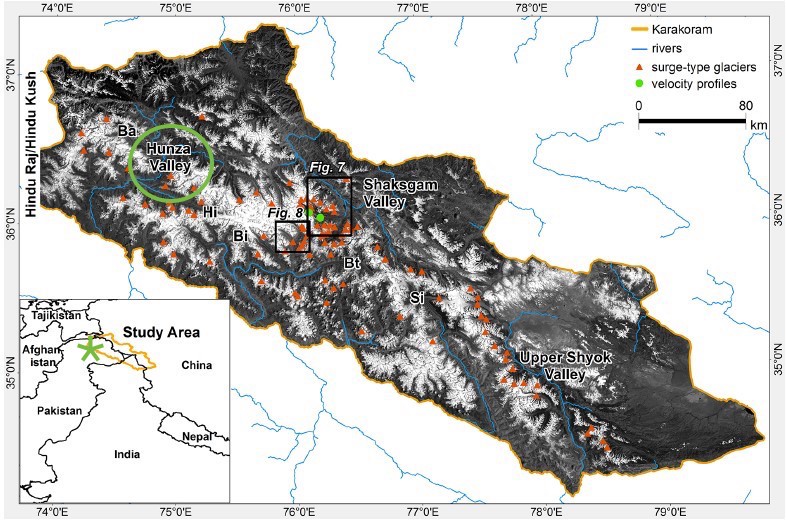

Map of Karakoram Mountain Range indicating glaciated regions. . The Hunza valley, circled in green, is the region discussed in this blog. Insert is a map of the larger region, including the Gilgit-Baltistan region highlighted by the green star. Figure credit: Rankl et al., 2014.

The Karakoram Range is one of the most ice-covered regions outside of the poles and has experienced changes to the glaciated areas in recent times. Many glaciers have grown or experienced balanced mass (where ice loss through melting is balanced by mass gain through snowfall), compared to the retreating glaciers throughout the majority of the world (Rankl et al. 2014). The glaciers in Karakoram have shown many surge events (short-lived glacier growth) and advancement (longer-term glacier growth) in the last decade, despite the rising temperature trend.

Passu peaks, also known as Passu cathedrals, standing behind Gojal Lake (on the right). Photo credit: Shan A Rajpoot, unsplash.com.

Impacts of Climate Change

Climate change is affecting people in mountainous Pakistan in many ways. On one hand, there are some positive impacts. For instance, the increasing temperatures are enabling the once cold regions to survive better, with more agriculture and bearable weather for the people. Similarly, the unprecedented rainfall change has allowed the once dry slopes of the barren mountains to flourish with grasses and shrubs. However, there are also many more glacial natural hazards, such as Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOF), a sudden release of water from supraglacial lakes (lakes on the glacier surface) or terminus lakes (at the end of the glacier). Floods are the most destructive form of natural hazards here because of their power to cause destruction in a short span of time with long-term impacts on the landscape and lives of the inhabitants. One of the largest social issues affecting the region is the lack of fresh drinking water for the inhabitants.

Regular Glacial Lake Outburst Floods events, like the one at Ghulkin glacier in 2008 shown here, damage infrastructure and properties. Photo credit: Pamir Times.

Water Supply Issues

The region of Gilgit-Baltistan in northern Pakistan (see the green star on the Map above) has many glaciers, high altitude lakes, springs and fresh-water streams and rivers. However, most of the population still lack a sufficient supply of drinking water. The domestic water supply system varies from region to region, but the irrigational water supply system is the same in the whole area. The source of water is from a spring at the base of the lateral moraines (deposits of rock and debris at the end of glaciers) which mark the boundary between the settlements and the glaciers’ main melt water route. The glacier melt water is channelized by constructing water channels from the spring towards the villages. That water is then used for irrigation, as well as and stored in small ponds for drinking use, once the sediment has settled down to the bottom of the ponds.

There are many reasons for water insecurity, but most prominent are the lack of government projects and decisive policy making. The terrain is highly challenging, so bringing fresh water to the settlements, especially through the mountains and steep cliffs, is often too difficult. As most of the water sources depend on runoff from the glaciers, changes in glacier dynamics due to climate change directly affect this supply system. Traditional water channels, built to bring glacial melt water to communities, are becoming ineffective with the change in the position of the glaciers’ termini (the end of a glacier). The growing season usually starts in March, when the first melt water from melting snow reaches the water channels, and ends in September, as the autumn season starts. The local communities lack funding and machinery to relocate or renew the water channels in the short time period before the start of growing season.

Economic Issues

The traditional economic activities in this region are mainly based on livestock and small-scale farming. Climate change is increasingly shifting the economic activities away from farming and agriculture to working in private and commercial sectors. High in the mountains, the summer grazing culture is shrinking, in spite of the growing grassland due to more rainfall and mild winters. Many factors have contributed to this downfall, such as more economic opportunities in the towns, rise of the tourism sector, tendency towards education and the lure of cities (jobs in towns and cities are seen as indicators of a modern, educated society with better living standards).

Communication is crucial

The response of glaciers to climate change depends on the size and location of the glacier, as well as the topography and localized climate of the region. The changing cryosphere conditions in this region, especially in terms of glacier dynamics, are key research areas at the moment and are often studied with minimal data availability due to the harsh and inaccessible terrain. However, very little attention has been given to communicating this research to local inhabitants. The local people have a lot of accumulated knowledge about the glacier dynamics, with practices passed down through generations, but it would greatly benefit from the state-of-the-art scientific research knowledge. The inhabitants are the front-line force to cope with the study of the impacts of changing climate in their region. Without involving them in research, science may be progressing, but not for the benefit of the local people. One of the main purposes of science should be for the betterment of humanity on this beautiful planet.

Further reading:

- Rankl, M., Kienholz, C., and Braun, M.: Glacier changes in the Karakoram region mapped by multimission satellite imagery, The Cryosphere, 8, 977–989, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-8-977-2014, 2014

Edited by Jenny Turton and Marie Cavitte

Shakir Ahmed comes from Gulmit, a village in Gojal valley located in upper Hunza region of north Pakistan. He lives in Germany and is currently doing his masters at the Friedrich-Alexander University in Erlangen, Germany. He studies Climate and Environmental Science. He is particularly interested in mountain climate and glacier dynamics, remote sensing, impact of climate change on mountainous communities and science communication.

Shakir Ahmed comes from Gulmit, a village in Gojal valley located in upper Hunza region of north Pakistan. He lives in Germany and is currently doing his masters at the Friedrich-Alexander University in Erlangen, Germany. He studies Climate and Environmental Science. He is particularly interested in mountain climate and glacier dynamics, remote sensing, impact of climate change on mountainous communities and science communication.

![For Dummies – How do wildfires impact permafrost? [OR.. a story of ice and fire]](https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/cr/files/2019/10/DJI01011-161x141.jpg)