Both glaciological research conducted in the field, and in the office, are vital — and ‘count’ as glaciology. Often, however, those of us who remain in our cozy offices can be forgotten, or thought to lead a ‘boring’ job. Alex Bradley, a modeller of glaciers, is here to remind you why the office glaciologist is fundamental to the Cryosphere, and why glaciology from a distance is key to the future.

I’ve never been to the field, but I am a glaciologist

I have never been to Antarctica. Nor Greenland. Or anywhere north of Scotland, for that matter. Only last year, did I first set foot on a glacier, and even that was during vacation. But I am a glaciologist, and the fact that I have never visited glaciers or ice sheets in the field doesn’t change that.

I’ve never ridden a skidoo. Nor have I instrumented a crack to see how fast it’s growing. I wouldn’t even know where to begin measuring the temperature of the sea from a boat. But the work that I do is important and vital.

Alex stood next to the Raikot Glacier in the Karakoram. Image credit: Alex Bradley

I work at the British Antarctic Survey, the UK’s national logistics provider for fieldwork to the Antarctic. Each September, the place becomes alive with ‘pre-deployment training’ – when those heading “South” for the (austral) Spring receive necessary training and information about the upcoming season. The place is a buzz, the excitement of fieldwork palpable. I pass through the concourse like an apparition, curious, but feeling like an outsider – and return to my desk to do glaciology my way: through screens and computers, crunching numbers and solving equations.

When my friends and colleagues return the following (boreal) Spring, I receive first-hand reports of their day-to-day routines. Night shifts on deck measuring the ocean, weeks camped on the ice listening out for icequakes, flights over the continent taking samples from clouds: to anyone outside this field, it might sound like science fiction.

My day-to-day routine is far more quotidian: today, for example, my morning consisted of checking in on my simulations, checking over some code written by a colleague, and starting a review of a modeling paper.

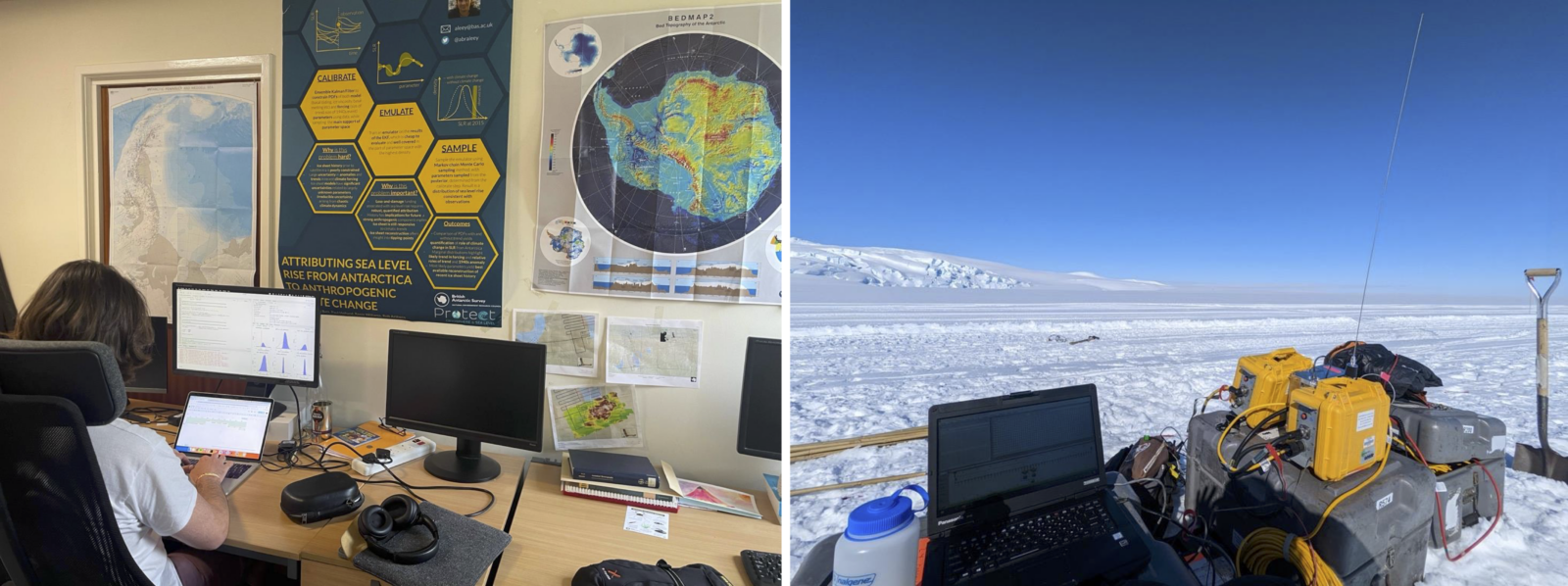

Left: The view from Alex’s desk as he runs models on glaciers and how they change. Right: The view from a field glaciologists desk as they collect geophysical data on the Ross Ice Shelf. Image Credit: Alex Bradley, Emma Pearce

“No, I’ve never been to Antarctica!”

The dinner party exchange is always the same: if occupations come up in conversation, the response is usually “Oh, cool! Do you get to go to Antarctica?” “No”, I respond, “I make models of the ice sheets and use them to make predictions about the future”.

The response of my friends generally reflects a sense that studying Antarctica takes place on the ground, in the cold. This image is the result of a century of exploration which provided narratives and stories about the continent. The race between Scott and Amundsen to the South Pole is as compelling as any fiction story, the epic voyages of James Clark Ross cast our minds to a time of discovery. (These stories also – problematically – frame Antarctica as a place only for men, only for those not disabled by our systems.)

These stories are epic for a reason: humans are not designed to be in Antarctica. The average temperature there, for example, is -43 degrees Celsius, almost 20 degrees colder than the coldest ever temperature recorded in the UK. That, combined with the sheer scale of this vast continent, means that even the best-organised fieldwork can’t hope to assess more than a small patch of this place (and even then, that’s when everything goes to plan, which rarely happens!).

A New Age of Glaciology

This is where technology, and my job, comes in. Advances in satellite technology, machine learning, and computational power are ushering in a new age of glaciology: that which takes place in the office.

Satellites are now able to track the motion of ice sheets at extremely high spatial resolution, providing an ever more detailed picture of how they are responding to climate change. Projections of sea level rise – probably the greatest threat from the World’s ice sheets – come from models built from thousands of lines of computer code.

These technologies have allowed us to do really important work, and to understand the World’s ice sheets in a way that we never could from fieldwork alone. We know almost exactly how fast ice sheets have flowed in recent decades, providing a compelling picture of how ice sheets respond to climate change – and thus a call to action. We can provide policymakers with the information they need to make informed decisions about adaption to sea level rise in the future. In my opinion, these are some of the biggest questions in glaciology, and being able to inform on them makes my job really rewarding.

With the ongoing revolution in artificial intelligence and autonomous technologies such as drones, the importance of the office glaciological will continue to grow.

There are added benefits to shifting toward glaciology in the office. Fieldwork naturally takes place in remote regions, making it extremely carbon intensive. Fifty percent of the entire carbon emission of the British Antarctic Survey is from the fuel used to power its ship, the RRS Sir David Attenborough. It’s also extremely expensive.

Glaciologists on the KANG-GLAC cruise to the Arctic on board the RSS Sir David Attenborough. Image Credit: Bryony Freer

The Importance of Collaboration

But, we can’t do everything from afar. Fieldwork remains extremely important. Satellites can only give us a broad view of the continent’s skin; lots of details can only be figured out by diving deep beneath the surface of an ice sheet. The ICEFIN project, for example, has revolutionised our understanding of what happens underneath ice shelves, providing an incredibly detailed picture of melting beneath over a kilometer of ice – impossible using satellites.

Our models are also informed by, and validated against, observations made in the field. Field surveys tell us things like how ice is sliding over the Earth beneath it, which are then incorporated into models. The future lies in a relationship between field and office glaciology. An excellent example of this is the Bedmachine project, which draws observations of the topography beneath the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, with physical modelling, to provide our best estimate of what the undulations beneath these continents truly look like.

When I tell people that I haven’t been to Antarctica, there is a pang of sadness. It’s only a pang, but it’s there, an element of FOMO (the ‘Fear Of Missing Out’). Every day at the moment, when I check Instagram, I am confronted by beautiful images from friends on the KANG-GLAC cruise currently taking place around Greenland and wish, for a moment, that I was witnessing with my own eyes what I see in another form on my screen every day. But, it’s only for a moment. I’m quickly reminded that the work I do is vital, fulfilling, and interesting, and can only be done from the comfort of my office.

Further Reading

Find out more about Alex’s research by reading his latest paper here or checking out his website!

You can also see some of the media coverage of Alex’s work and why it’s so important in the following news articles!

- The Guardian – Newly identified tipping point for ice sheets could mean greater sea level rise

- British Antarctic Survey – New tipping point discovered beneath the Antarctic ice Sheet

Edited by Emma Pearce