Sea ice is a critical part of the unique Arctic ecosystem, but climate change is becoming a serious threat. Warming in the Arctic has already resulted in the loss of over 4 million km² of sea ice. But is it all bad? Retreat of Arctic sea ice is allowing more ships to navigate the Arctic Ocean, along shorter, faster and cheaper sea routes, providing emission reductions of 24%. But will the growth of shipping sign the death warrant for Arctic sea ice? Read on to find out!

A frozen landscape… on the edge?

Sea ice is a vital component of the unique Arctic ecosystem. Constrained to the Arctic Ocean, sea ice comprises a thick core surrounded by seasonal ice, which undergoes annual cycles of melting and freezing. Sea ice is critical – it’s what keeps the Arctic cold, reflecting heat energy from the sun with its bright white surface, and keeping the Arctic Ocean frozen throughout the year. However, a process called Arctic Amplification is threatening the sea ice. A concept associated with global warming, Arctic Amplification recognises that, in recent years, the Arctic has been warming faster than the rest of the world: Rantanen et al. (2022) suggest up to four times faster! This makes the Arctic particularly vulnerable: a warming world means melting ice, and less sea ice in the Arctic means that the sun’s heat energy is no longer reflected, but instead absorbed by the ocean. In a domino effect, a warming ocean then accelerates even more sea-ice melt, exposing more ocean, and causing more warming. It’s a dangerous loop, which could lead to rapid environmental change and an Arctic we no longer recognise.

A defrosting Arctic

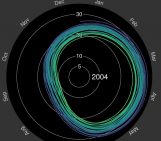

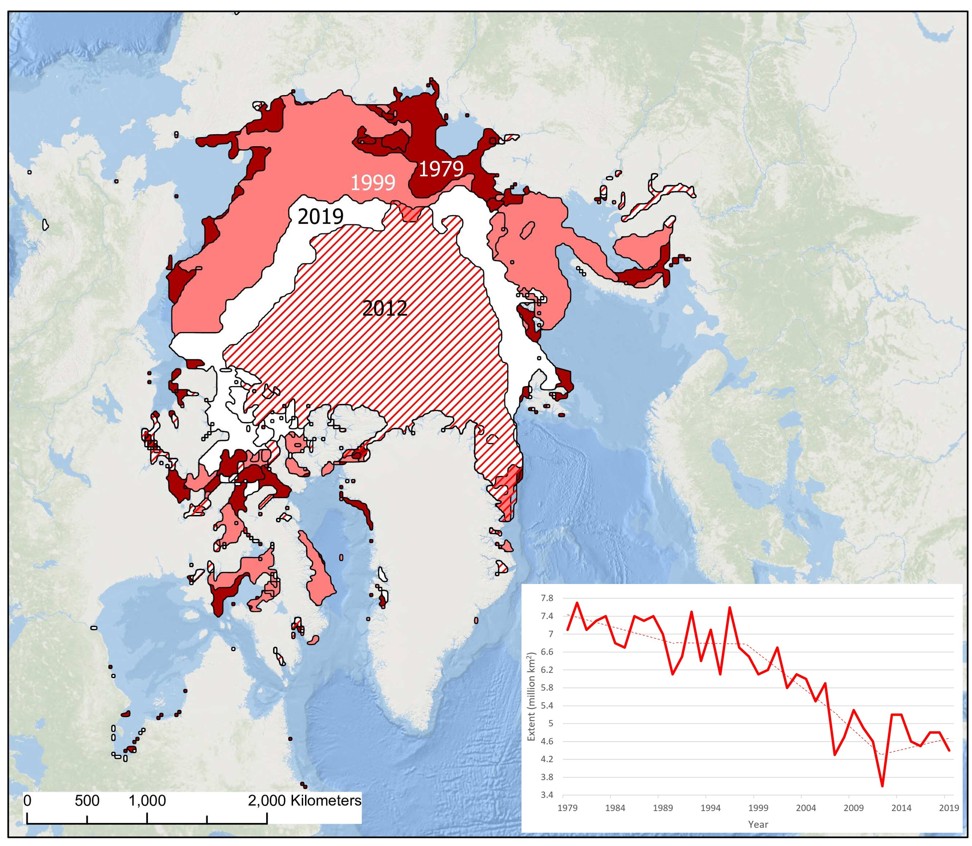

Global warming has already had severe consequences. Since 1979, the winter sea-ice maximum extent retreated by 10%, and the summer minimum extent by 38%. That’s a loss of almost 1 million km² per decade, and total loss of 4.4 million km² over 40 years. To put that into perspective, that’s half the area of the USA, or half of Europe – the Arctic is undergoing some serious defrosting! In Figure 2, we can see just how far summer sea ice is retreating; since 1979, summer sea-ice extent has almost halved and is now almost completely constricted to the central Arctic Ocean.

Figure 2: Map showing September sea-ice extent from 1979-2019 at twenty-year intervals, supported by a graph showing annual sea-ice decline. [Credit: Lily Thompson].

Polar Pathways

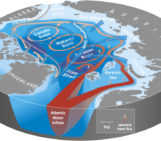

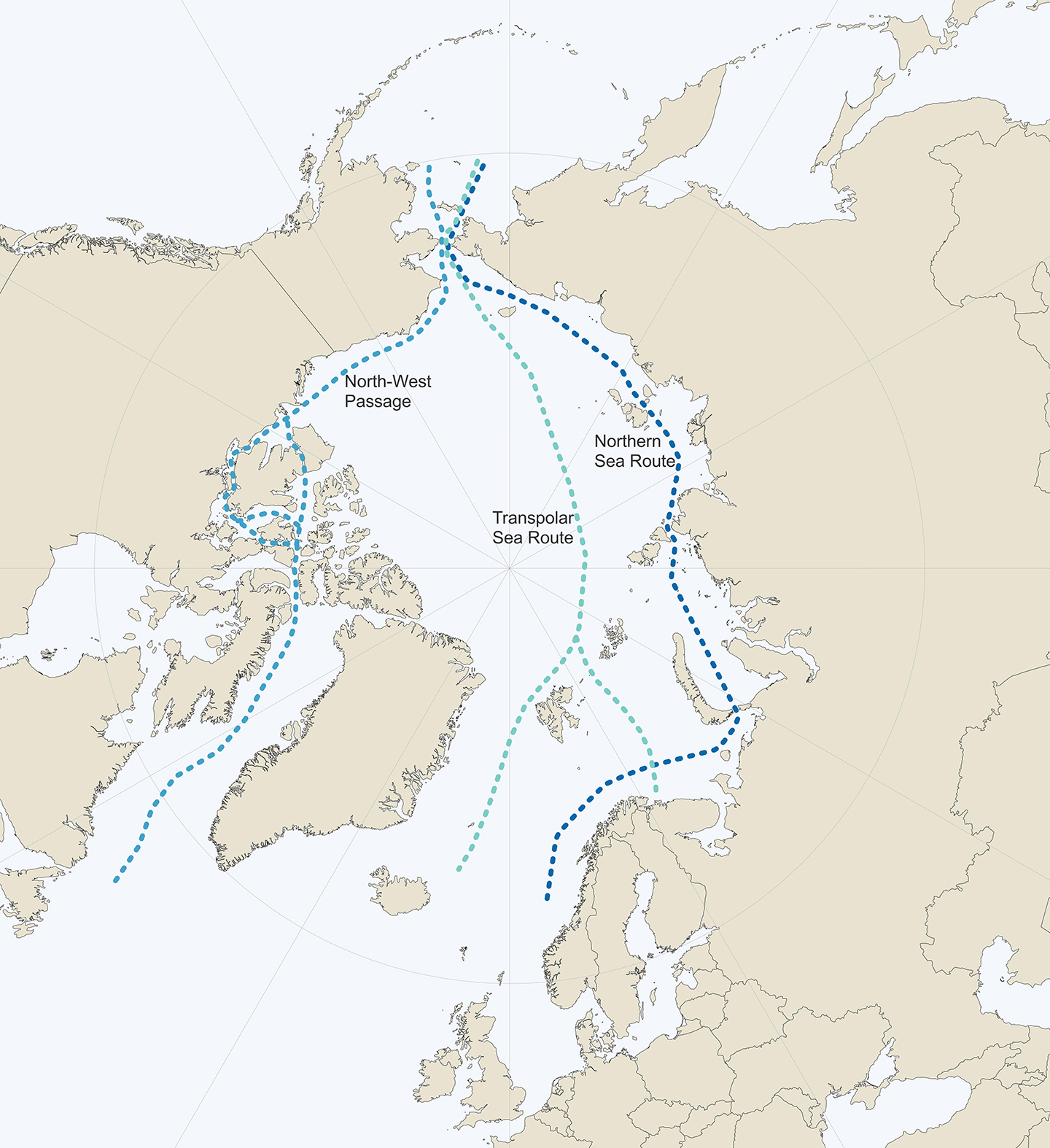

The Arctic also accommodates various waterways (see Figure 3). Its longest passage, the Northern Sea Route, runs along the Russian coastline. Stretching 5600 km, it is a key feature of Russia’s Exclusive Economic Zone, as well as providing a maritime pathway connecting Europe and Asia. While the Northern Sea Route faces sea-ice obstructions, its potential as a shipping route is powered by its ability to reduce shipping distance and time by 50% compared to other global trade routes. In fact, using the Northern Sea Route beats shipping via the Suez Canal by 15 days, making it increasingly attractive to global trade. However, the remote location of the sea route poses challenges: narrow straits along the pathway demand ship size limitations, and with the Arctic region as a relatively new shipping location, it lacks port infrastructure. For these reasons, the Northern Sea Route has not yet reached its full potential.

Figure 3: Mapped pathways of Arctic seaways: the Northern Sea Route (dark blue), the Northwest Passage (light blue) and the Transpolar Sea Route (green). [Credit: Arctic Centre, 2023].

There exists a third Arctic shipping route, however it is one that history is yet to traverse. The Transpolar Sea Route is 3800 km long, and directly crosses the North Pole – this pathway would represent the fastest journey across the central Arctic Ocean. However, there remains one HUGE icy problem… the entire route remains, to this day, blocked by sea ice. So what’s it worth? The Transpolar Sea Route is a frontier of the future, increasingly accessible as the Arctic continues to warm and the sea ice melts. It would require an icebreaker escort, but Bennett et al. (2020) suggest that summer use of the Transpolar Sea Route could be possible within 50 years.

So what’s the link?

The fact is that rapid sea-ice decline in the Arctic is what’s causing the marked rise in shipping through the Arctic Ocean. Observations show that shipping traffic has increased the most during the summer months, coinciding with the greatest annual losses in sea ice. Retreat of the ice away from the coastlines is opening up the waters along Arctic sea routes, making them more accessible and more reliable for shipping. The Northern Sea Route has seen particular growth, with a 540% increase in cargo volume along the pathway since 1980, as well as a growth in ship count of 72.5% on Canada’s Northwest Passage. On top of this, statistical analysis supports that the accelerated rate of sea-ice decline since 2000 is the direct cause of amplified shipping along Arctic sea routes with a confidence level of over 99%. This new open-water access has also enticed 8.3 million annual tourists to the Arctic region, and offers shipping emissions reductions of up to 24% through more direct routes.

So, it’s full steam ahead, right? Wrong. Shipping along Arctic sea routes is still highly vulnerable to unpredictability. Results show that in years with highly variable sea-ice extents, shipping traffic is massively reduced, with unpredictable sea ice making maritime transport unsafe and unreliable. In addition to this, the initial emissions-saving benefits of faster shipping in the Arctic are temporally limited: with more ships operating along these shorter transport routes, total emissions are actually rising. As a result, the environmental impacts of Arctic shipping beg the question of whether the shorter transport time is really worth it. Not only has reduced sea ice driven increased shipping, but increased shipping has further accelerated sea-ice decline, triggering exceptionally low sea-ice extents which present a threat not only to the Arctic marine ecosystem, but also to global temperature. By eliminating the critical reflective sea-ice surface, shipping is indirectly contributing to warming on a global scale, churning up the ocean surface to prevent sea-ice re-freeze. Therefore Arctic sea routes, despite their economic benefits, could have disastrous environmental effects, with localised impacts from shipping pollution exacerbating to global-scale climate warming. If these growing shipping trends continue, we are taking huge steps towards an unrecognizable, ice-free Arctic, after which there may be no chance of environmental recovery.

Future projections: an ice-free Arctic?

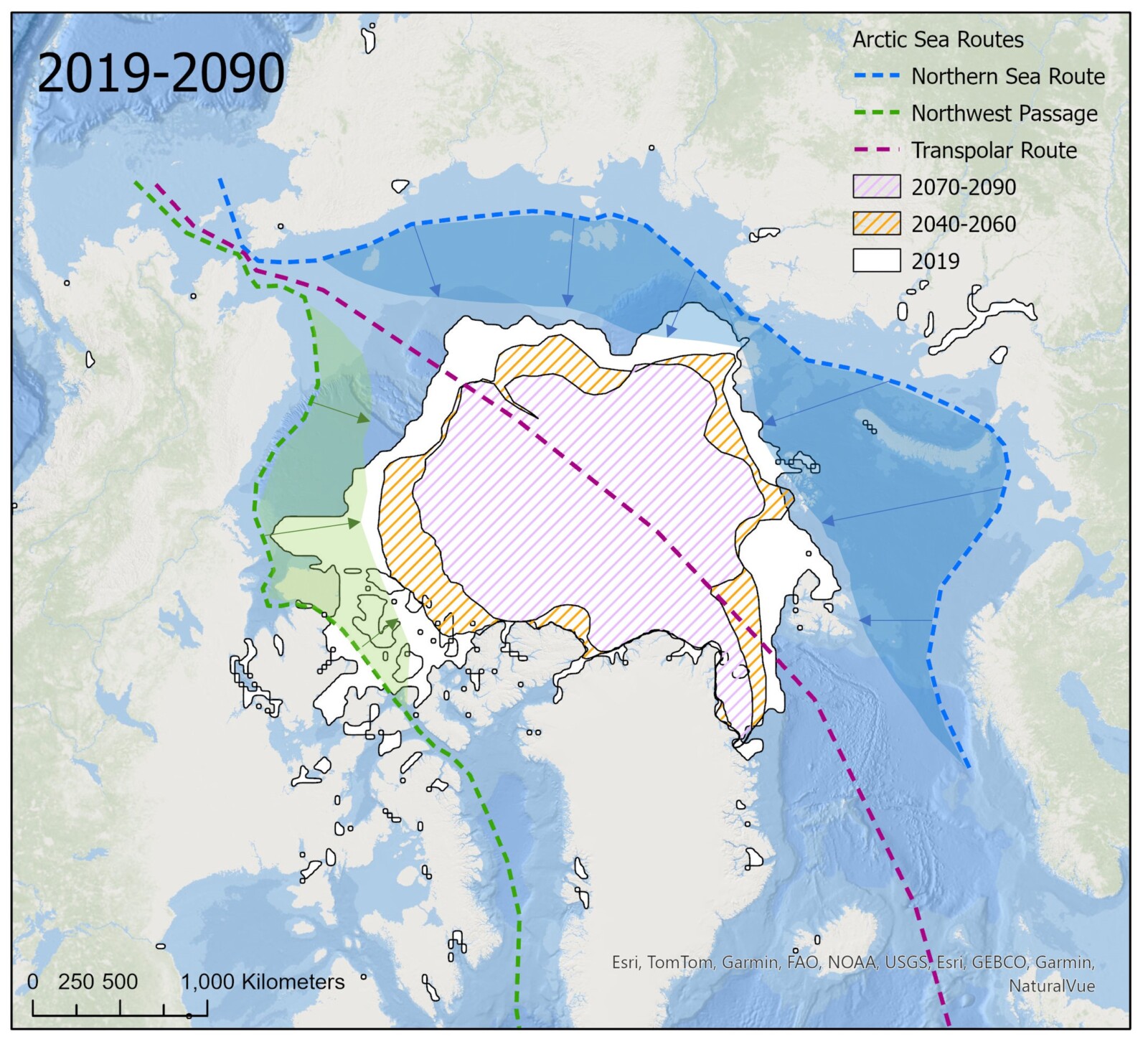

For sea routes to succeed, the Arctic will need to undergo considerable environmental change, with future warming continuing to accelerate sea-ice decline. However, these critical tipping points might be closer than we previously estimated. Models project that Arctic sea ice could retreat another 1.2 million km² by 2060, and almost 2 million km² by 2090 (see Figure 4). However, at its current rate of decline, we could see the Arctic reach the “ice-free” threshold (1 million km² total) as early as 2050. This change would mark a significant tipping point in the Arctic, after which it is uncertain as to whether the sea ice could recover to its previous extent.

Figure 4: Map showing projected sea-ice extent from 2019-2090 and resulting northwards migration of Arctic sea routes. [Credit: Lily Thompson].

So what’s your verdict? Are the economic and time-saving benefits of Arctic shipping worth the potential environmental degradation? Important decisions being made now will shape the future of the planet – we must choose between human development and environmental protection, but only one of those things will benefit both people and planet in the long run.

Further reading

- Rantanen et al. (2022). The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979, Communications Earth and Environment 3.

- Stroeve et al. (2014). Changes in Arctic melt season and implications for sea ice loss, Geophysical Research Letters 41(4).

- Melia et al. (2016). Sea ice decline and 21st century trans-Arctic shipping routes, Geophysical Research Letters 43(18).

- Wei et al. (2020). Projections of Arctic sea ice conditions and shipping routes in the twenty-first century using CMIP6 forcing scenarios, Environmental Research Letters 15(10).

- Bennett et al. (2020). The opening of the Transpolar Sea Route: Logistical, geopolitical, environmental and socioeconomic impacts, Marine Policy 121.

- Finally, check out the Cryosphere Glossary.

Edited by Emma Pearce and Lina Madaj