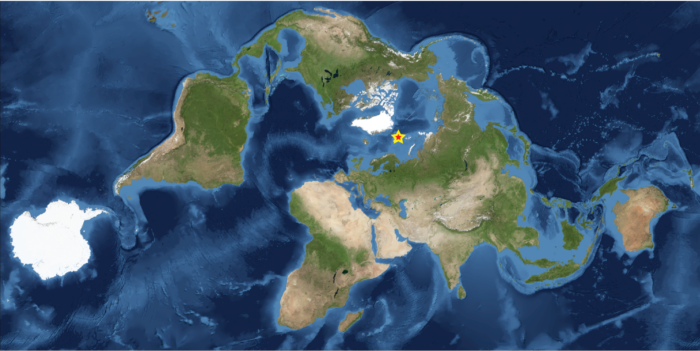

Around the summer solstice of 2022, a small group of twenty young researchers met in Svalbard, a small island lost between Norway and the North Pole. The Norwegian Scientific Academy for Polar Research wanted to bring us together around the theme of “The Global Arctic“. The scope of this summer school was to “produce a better understanding of the significance of the concept of Global Arctic as a tool of integrative analysis and political management, as well as discussing points of connection within and between the natural, social and human sciences“. From outside and inside the Arctic, we came to seek and research together.

Longyearbyen, the gateway to the Arctic

For most of us, this was the first time we set foot in the Arctic. For me, it was a return to the place where I first walked on sea ice six years ago. During our stay, the height of the sun did not change that much, it was just traveling around us, around the two cliffs on which lie the remains of the coal mines that sustained the town for almost a century.

With its 2,000 inhabitants and located in Svalbard, Longyearbyen is today mainly structured around Arctic tourism and its university. Longyearbyen’s unique location is a direct gateway to the Arctic, a region that is much more connected to the rest of the world than one might think. And often not in a good way. Temperatures there have risen three to four times faster than globally and pollutants from around the world are piling up and will persist for decades.

What is happening in the Arctic therefore gives us a glimpse of our future in the context of global warming and how people and communities will have to adapt to these changes. The rest of the world has much to learn from the Arctic, but this requires effective communication across disciplines and beyond academia. This is what we have tried to do during this summer school and this is why I joined it. It was exactly what I was looking for. A place and a time to share our experiences and contribute to building a global vision of the Arctic. I invite you to follow me on this journey across disciplines and knowledge.

What better way to break the ice than teamwork and a cold bath in the Arctic Ocean. Photo credit: Ragnhild Utne.

Why spending time together matters?

We spent 10 days together, during which we met agents of change, people who have been acting for more than 30 years at the interface between science and governance. With Grete K. Hovelsrud, Bjørn P. Kaltenborn, Thor S. Larsen, Lars-Otto Reiersen and many others, we learned first-hand what interdisciplinarity really means. It is always different to be aware of their work and to realize that the Arctic Council was created by one of them or that the first international law on the protection of polar bears was signed by one of those hands I shook every morning. Getting to live with these people, having a daily cup of coffee and walking along the fjord with them, brought us into the same reality as theirs.

I am convinced that our reality is a matter of perception, and that knowledge alone is not enough. And this applies to climate change. Today, access to knowledge is easy, but access to the experience of that knowledge, to the emotion linked to this knowledge is ineffective. When I started my PhD, I thought journalists, politicians and civil society would approach scientists of their own accord. I thought scientific knowledge would find its own way because of its strength, but it seems that until knowledge is experienced physically or emotionally, nobody really understands its importance.

Perhaps this is why our society still does not see what a warming and melting world means, despite clear statements from the scientific community. It is a question of perception and commitment. Even in Longyearbyen, a town at the heart of these changes, perception issues are present and it took extreme events affecting its inhabitants to start creating a global awareness of climate change. The book “My World is Melting” by Line Nagell Ylvisåker, a journalist based in Longyearbyen, is a very good example of how direct experiences change the perception of climate change.

Such experiences redefine our imaginary and what we think possible. By ‘imaginary’, or social imaginary, I refer to the system of meanings that govern our social structure. This is what John B. Thompson describes as “the creative and symbolic dimension of the social world, the dimension through which human beings create their ways of living together and their ways of representing their collective life“. In Longyearbyen, we questioned and shared our imaginary by spending time together. But understanding each other was not always easy.

The struggle to build a common imaginary

We all came from diverse backgrounds and with our own stories. In interdisciplinary work, you have to adapt your language to your collaborators. Trying to understand where each of us came from was key to our exchanges. Working together meant getting out of our siloed disciplines.

It may sound simple, especially for young researchers, but it was not. Even between people who are aware of the same cause and know the Arctic. It was not the first time I had been in such a situation, but it really highlighted how separate we can be from each other, even within the academic world. So when it comes to talking to civil society, politicians or other experts, the challenge becomes even greater.

I thought that my way of thinking, my knowledge, was accessible to everyone, was not so complicated to understand. We use words and concepts for so many years that they become so familiar to us that we assume everybody understands them.

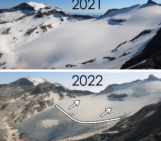

What we tried to do in Longyearbyen was to understand how to share knowledge, how to link expertise and transfer our knowledge in a readable and understandable way. From a personal point of view, it was not only about writing an interdisciplinary paper, but also about gaining a new way of looking at things. I am not saying it all happened in a week, and I have been trying to navigate the interfaces for a decade while gaining expertise in my research area. But now I see what it really means to be an expert, to have legitimacy, and this interdisciplinarity has added meaning. It reminded me why I study glaciers. It reminded me that it is about sharing their stories, with you and others.

The hike to the melting glaciers and the joint dinner were as crucial as the lectures for the success of our project. Photo credit: Ragnhild Utne.

Why is interdisciplinarity so important?

Since the Cartesian revolution more than 400 years ago, we have learned to put problems into boxes and treat them independently of each other, thinking that the whole is simply the sum of the parts. This is what we have done in academia, in industry, but also in our lives. It has allowed us to explore the unknown at an unprecedented level, to go further in all directions, again and more. It has allowed us to create tools and machines capable of things we could not have imagined only 20 years ago. But it has also made us sometimes forget the big picture, our connections with others and the world.

We have learned to disassociate ourselves from each other, and I am a prime example of this, as an expert in the physics of glacier sliding. Over the past decade, I have moved from one country to another on average every two years. I have gradually cut ties, created new ones, but above all I have specialized myself in a very specific field of scientific exploration. Sometimes, I forget the importance of links and I give too much importance to my scientific work. And that is where interdisciplinarity helps me.

Interdisciplinarity is not just about putting experts side by side and having them discuss and juxtapose their knowledge. It is about creating a different kind of knowledge. It is about accepting that the whole is more than the sum of the parts. I believe that we must connect the elements that we have learned to separate, if we are to ensure cooperation between researchers, citizens and stakeholders. To connect, that is not just to make an end-to-end connection, but to make a looping connection.

To do this, we discussed the links between these elements and accepted their complexity. In its literal sense, complexity means woven together. This word has been in my vocabulary for a long time thanks to numerous discussions with dear friends who teach refugees in Greece, study egalitarian indigenous communities in Congo or work on a film set in Mongolia. But these 10 days in the Arctic have allowed me to discover its full meaning, because we wove together.

There are a lot of theories about how to make different disciplines work together, and I was inspired by reading about the organization of social movements. The key to this was to listen to each other and accept our different languages while being aware of where we came from and why we were here. We all had our limits in terms of emotional and personal involvement in this project. We accepted them and it then became much easier to work together. What I experienced during this summer school will certainly influence the way I design and participate in future conferences and workshops.

What better way to experience interdisciplinarity in the Arctic than to go to the front of a calving glacier with a marine biologist, a social anthropologist and a glaciologist? Photo credit: Ragnhild Utne.

How did we train our interdisciplinarity?

Every morning we would go down the valley, leaving the glaciers behind, and head towards the fjord. And every evening we would return to our huts. We had a good thirty-minute walk, a time to meet each other, one on one. We got to know each other and work together during meals, hikes and discussions in small groups.

The organization of the summer school, with lectures in the morning and group work in the afternoon, gave us all the space we needed for interdisciplinarity. Conflicts arose and provided an opportunity to practice. We had some tense moments, often due to a question of identity or language. These were opportunities to get to the heart of the matter of communication between us. It would be an illusion to think that interdisciplinarity can be done without conflict, but conflict is not necessarily a bad thing and has allowed us to let off steam sometimes. The long walks along the fjord in the wind gusts often calmed us down.

Each group had its own dynamics, each had its own way of doing things and from one work session to the next you could feel the atmosphere change. I tried to capture the coherence of the project, to work on this common ground and build a shared imaginary. Bringing people together is not easy, it raises questions of legitimacy and humility. But it can take various forms, because a leader is not necessarily the one in the limelight. In the end, we all contributed in our own way, as far as we wanted to.

What’s next?

Almost three months after that summer school, we are trying, despite the distance and time zones, to finish our joint project and submit it to Polar Geography by the end of the year. Once we left Svalbard, once we were no longer in the same room, our daily lives caught up with us so quickly. Between those going out into the field, those finishing their degree, those changing jobs or going on holiday, it is not easy to stay close and especially to keep working together. But somehow it has continued, as if something emerged during this summer school, making us work not only across our disciplines but also across boundaries. Melting boundaries.

Further reading

- NVP International Summer School 2022 – The Global Arctic: the website of the summer school in Svalbard.

- The David Graeber Institute, on working together to address the current crisis. It provides valuable insights into how our imaginaries construct our society.

- The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, one of the six working groups of the Arctic Council, has successfully brought together Arctic researchers and citizens to address environmental challenges.

- A research group at University College of London working beyond interdisciplinary with extreme citizen science.

- Bruno Latour, a French socio-anthropologist who has studied the ways in which scientific and technological studies are conducted.

Edited by David Docquier and Marie Cavitte

Ugo Nanni is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oslo. From the Alps to the Arctic, he listens to the whisper of glaciers. When he is not conducting research, he shares the voice of glaciers and tells their story beyond the academic world, as he will do at the Cryosphere Pavilion during the COP 27. Ugo is also on Twitter (@NanniUgo) and you can contact him at ugo.nanni@geo.uio.no.

Telkom University

What initial assumptions did the author have about how scientific knowledge would be received by journalists, politicians, and civil society?