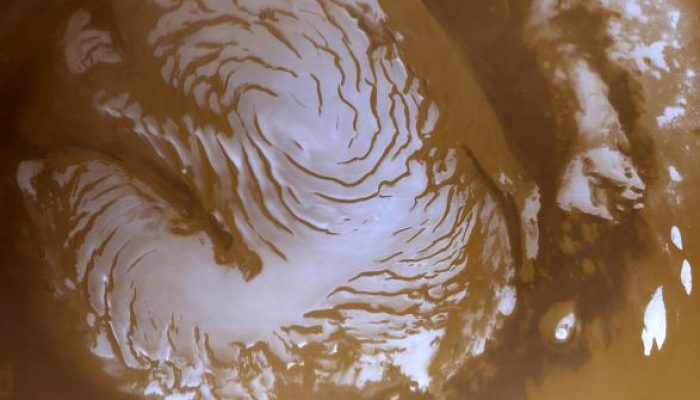

Much like our Planet Earth, Mars has polar ice caps too, one for each pole: the Martian North Polar Ice Cap (shown on our image of the week) and the Southern Polar Ice Cap. Yet, their composition and structure reveals these ice caps are quite different from those of Planet Earth…

Mars refresher

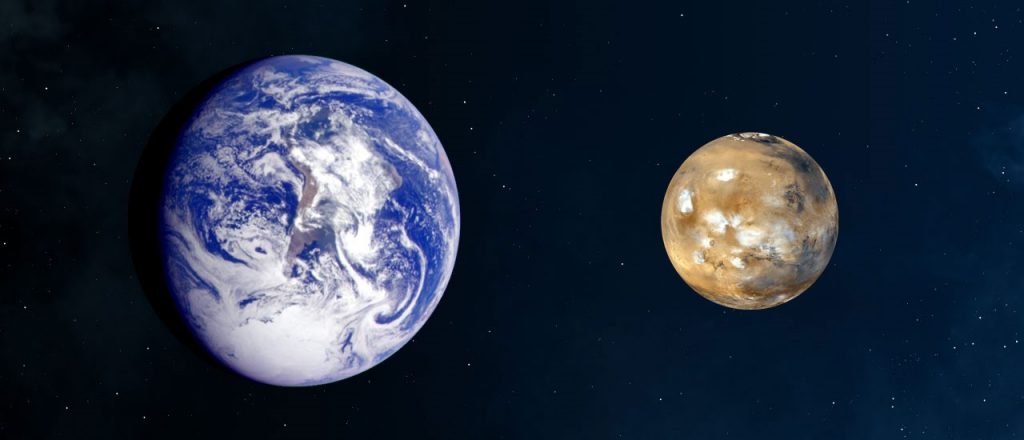

Planet Earth and planet Mars [Credit : NASA]

As a refresher, here are some Mars facts:

- Mars is the 4th planet from the sun.

- Its equatorial diameter is half the size of the Earth’s, but is bigger than our moon’s.

- Its mean surface temperature is -63°C (the Earth’s surface is around 14°C)

- Mars’ atmosphere is 96% carbon dioxide, less than 2% argon, less than 2% nitrogen and less than 1% other gases.

- Mars’ rotational axis has a tilt similar to Earth’s giving it four seasons as well .

For more detailed pictures and facts about Mars, go have a look on the NASA website here.

What are these Martian ice caps like?

Like Earth, both of Mars’ poles are frozen. It is the only place in the solar system besides Earth where you can find permanent ice caps. These two Martian ice caps are primarily made of frozen water… but not only! During the winter season, the poles permanent bulk of “water ice” are covered by a seasonal layer of frozen carbon dioxide (commonly known as dry ice).

How come? Similar to Earth, during each pole’s respective winter, these ice caps experience continuous darkness for several months. The temperature becomes so cold (freezing point is -126°C !) that carbon dioxide in its atmosphere freezes and falls onto the ground, forming layers of dry ice. In the summer when the sun returns and temperatures warm, the dry ice begins sublimating back into the atmosphere. At the North pole almost all the dry ice turns back into gas and the ice caps shows its water ice, while a layer of frozen carbon dioxide always remains at the South pole. Seasonal variations can thus be observed like those on Earth.

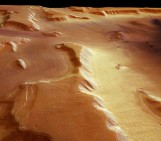

Martian North (left) et South (right) poles [Credit: NASA ]

The northern ice cap on Mars is much bigger than the southern one. It is about 1,000 kilometers wide (roughly the width of Greenland at its widest point) while the South pole is only 350 kilometers in diameter. Yet… they both contain the same amount of ice! If all of this ice was to melt, Mars’ surface would be covered by an ocean that was 18 meters deep. They are thus the currently largest known water reservoirs on the planet.

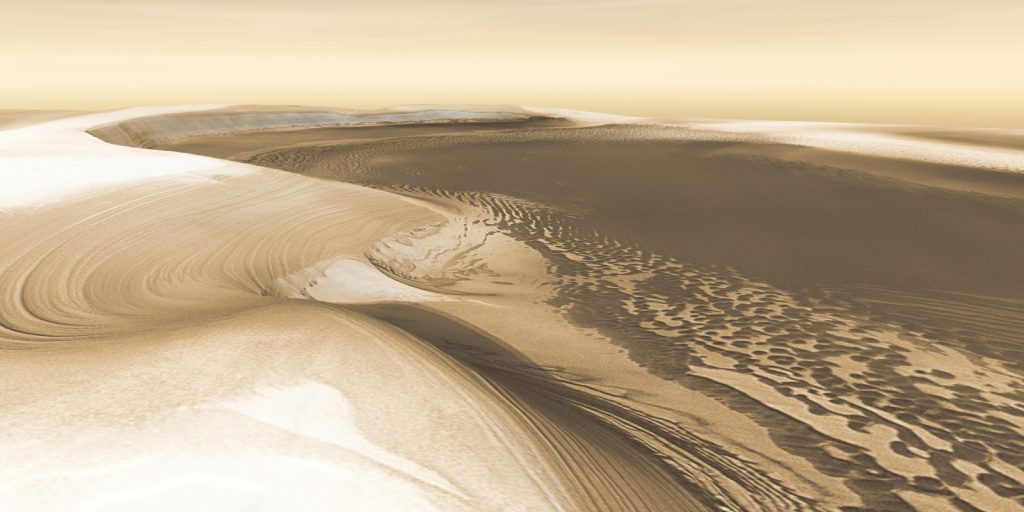

But… what are these spiral forms on Mars’ ice caps?!

The ice caps at both Martian poles show spiral throughs. According to the ESA, these unique features are the result of strong winds that spiral at the surface of the ice caps due to the same Coriolis effect that exists on Earth. This makes every fluid rotate to the right in the North Hemisphere and to the left in the South Hemisphere.

In the North Pole, one of these throughs, called Chasma Boreale, is particularly big. This 100-kilometer-wide and 2-kilometer-deep canyon roughly cuts the Northern Martian ice cap in half.

Chasma Boreale on the Northern ice cap [Credit: NASA ]

Drilling ice cores on Mars?

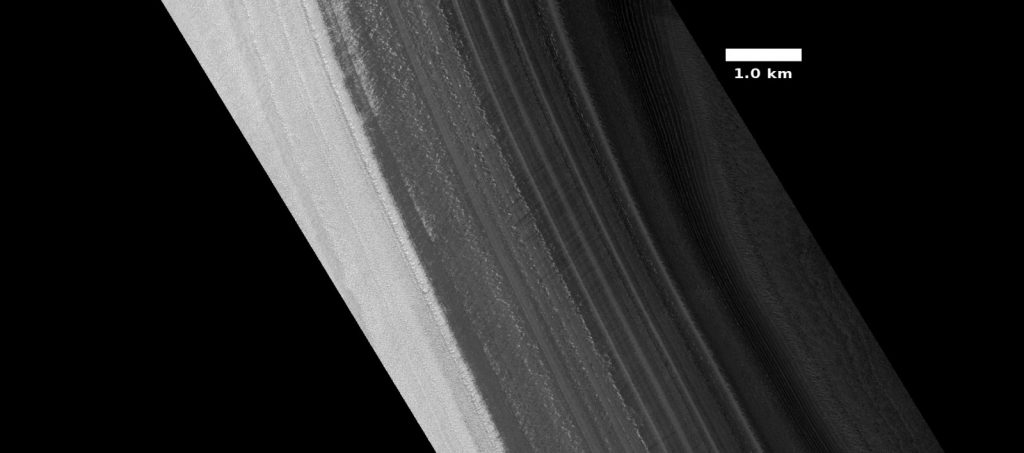

The seasonal melting and accumulation of ice occurs while dust deposits, which explain why both Martian polar caps exhibit layered features. They are thus composed of layers of ice mixed with dust (in the scientific jargon, Mars ice caps are called “Polar Layered Deposits”). As for ice cores on Earth, information about the past climate of Mars might be “trapped” in these dust layers. These are essential if we want to find proof of a time when liquid water existed on Mars! Unfortunately, ice cores have not been drilled… yet!

Layers in North Martian Ice Cap (The more dust, the darker the surface) [Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona ]

Further Reading

- Fishbaugh, K. (2001). “Comparison of the North and South Polar Caps of Mars: New Observations from MOLA Data and Discussion of Some Outstanding Questions“. Icarus. 154 (1): 145–161.

- Head, J.W., Mustard, J.F., Kreslavsky, M.A., Milliken, R.E., Marchant, D.R. (2003). “Recent ice ages on Mars”. Nature. 426, 797–802.

- Smith, Isaac B.; Holt, J. W. (2010). “Onset and migration of spiral troughs on Mars revealed by orbital radar“. Nature. 465 (4): 450–453.

Edited by David Rounce

Violaine Coulon is a PhD student of the glaciology unit, at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Brussels, Belgium. She is using a numerical ice sheet model to investigate the dynamics and stability of the Antarctic Ice Sheet for the past 1.5 million years.

Violaine Coulon is a PhD student of the glaciology unit, at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Brussels, Belgium. She is using a numerical ice sheet model to investigate the dynamics and stability of the Antarctic Ice Sheet for the past 1.5 million years.