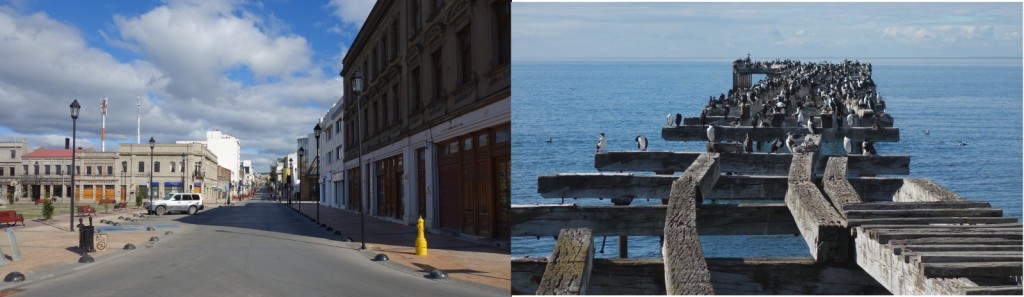

My Antarctic adventure started from Punta Arenas at the bottom of Chile, opposite Tierra del Fuego, on New Years Eve 2014 after a long journey from Heathrow via São Paulo and Santiago.

Punta Arenas

Punta Arenas is where Shackleton organised the rescue of his men from Elephant Island after his voyage to South Georgia in the James Caird. It is also where I met my PhD supervisors Chris Fogwill and Chris Turney for the first time, along with ancient-DNA expert Alan Cooper. Punta is the base for Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions (ALE), who are part funding my PhD and supporting me and my supervisors in the field.

Off to Antarctica…

After a couple of days in Punta Arenas, when the weather was right, we boarded an Ilyushin and flew the 4.5 hours to ALE’s base at Union Glacier in the Ellsworth Mountains. The Ilyushin is a big, rough-and-ready Russian transport plane equipped with an emergency rope instead of inflatable slides. We sat in the front half of the cabin and the back was packed with fuel and supplies for the base.

Union Glacier is a hub for an assortment of mountaineers, explorers, tourists and scientists. By Antarctic standards the base is very luxurious, with toilet blocks and even showers. Our bags were taken from the Ilyushin and were waiting for us outside our clamshell tent: “Scott”. All the tents are named after polar explorers and they have proper camp beds and solid floors inside. With regular Ilyushin flights, there is plenty of fresh food and the chefs cook fabulous breakfasts, lunches and suppers. The mix of people coming and going means that there are plenty of interesting stories to hear at mealtimes.

There was an American military man who had parachuted out of an Ilyushin to the North Pole, a cancer survivor who was trekking to the pole to raise millions of pounds for Cancer Research and lots of people who had climbed six of the seven summits and were in Antarctica to climb Mt Vinson, the last of the seven.

The fieldwork

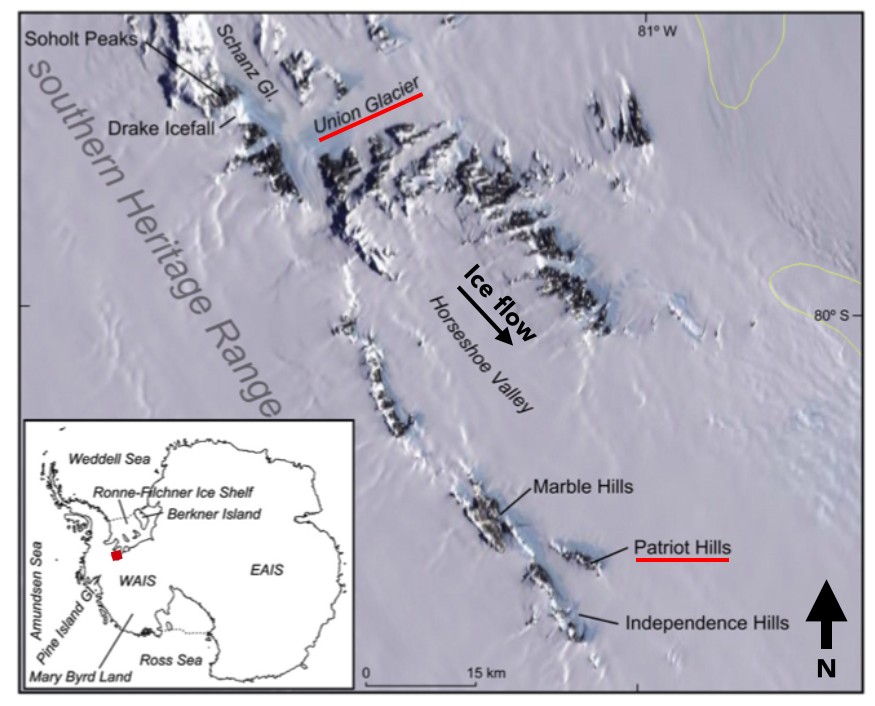

Map showing the Patriot Hills and Union Glacier. It took about 20 minutes for the Twin Otter to reach the Patriot Hills from Union Glacier base. (Credit: H. Millman)

Good weather meant that we couldn’t enjoy Union Glacier for long and soon the Twin Otter was loaded with all our equipment and the four of us were flown out to our field site: the Patriot Hills in the Horseshoe Valley.

The Horseshoe Valley is at the end of the Heritage Range, close to the grounding line in the Weddell Sea. Katabatic winds blowing down the side of the Patriot Hills have caused a blue ice area to form. The chance to sample the old ice, which comes to the surface in these areas, is what brought us to Antarctica. Over the next few weeks we drilled a snow/firn core, and ice cores in the blue ice area. Surface samples were collected by Professor Chris Turney, crawling 1.6 km on his knees as though trying to appease the God of the Glacier, with a cordless drill from a DIY store.

Once we get back to the lab, the samples will be analysed for trace gases, isotopes, tephra and ancient DNA. From this data we are hoping to extract a climate record reaching back to the Last Interglacial (~135 – 116 ka). I will then use this record, along with other proxy records and GCM outputs, to drive the PISM-PIK ice sheet model. This will help to answer the main question of my PhD, which is: What was the Antarctic contribution to sea level rise during the Last Interglacial? Global average temperatures during the Last Interglacial were 1-2°C warmer than pre-industrial times. As we move into a similar climate today, the past can be used as a process analogue for what might happen in the coming decades.

Drilling using a Kovacs corer. Here I’m wearing 3 coats: a light down jacket, a soft windproof shell, and my big down jacket on the top. I’m also wearing down trousers over my salopettes. It’s quite windy on the blue ice, so it can feel very cold. (Credit: H. Millman)

A digression on “everyday” life in Antarctica…

We set up our camp a little way away from the blue ice to avoid the worst of the katabatic winds. Camp consisted of a big mess tent and 3 sleeping tents. Fogwill and me had our own tents, but Turney and Cooper had to share. Turney and Cooper were struck down with colds and we took extra care to disinfect or quarantine anything the infected had touched because having a cold in Antarctica is a thoroughly miserable experience. Fortunately, we had lots of hot, hearty meals because ALE had sent us off with excellent frozen meals cooked by their chefs. We had curries, lasagna, stews, bread rolls and cake, and we only had to eat de-hy for lunch. The only food I missed was raw carrots.

For obvious reasons, snow for drinking water was collected up-glacier of the camp, and the latrine was located down-glacier. We took it in turns to collect and melt snow for drinking water. Our toilet tent had about 3 or 4 different incarnations as storms buried our previous efforts. By the end, we found the best design was dug down about 1 m, with snow blocks and fuel barrels around it supporting a wooden board and a sheet of tarpaulin. This stopped snow getting in during a storm, but the tarpaulin could also be wrapped around your neck so that one’s body could appreciate the warmth rising up from the latrine, while keeping one’s nose out in the fresh air. All waste is collected in containers so that it can be flown out to Chile on the next Ilyushin- all human waste has to be removed from Antarctica. Since the men have the advantage of being able to wee straight into the pee barrel, ALE kindly supplied me with my very own wee bucket, which I was extremely grateful for, particularly after an unpleasant incident with a SheWee at 3am, during a storm.

The good weather meant that we were able to work most days. We had a couple of stormy days which allowed us to rest, read, listen to music, tidy down the camp, and recharge our batteries (literally). Electrical things aren’t at their happiest in the Antarctic cold. My iPod wiped itself in the last week and we had to hug our laptops inside our jackets to keep them warm enough to hold some charge.

…back to reality

Once we’d collected all of our samples, it was time to leave the Patriot Hills and return to Union Glacier. We started packing things away while we were waiting for the Iridium call from the base, not knowing whether the Twin Otter would arrive that afternoon or tomorrow or the day after, or the day after that. We got the call and the Twin Otter was already on its way. A mad rush followed as we had to quickly but carefully dig out all of our tents from weeks’ worth of icy snow and pack them away. The plane landed less than 30 minutes later with the ALE guides who were going to take our skidoos back. With their help, we soon had everything loaded onto the plane, with just enough room for the four of us to squeeze in like sardines.

Quickly packing up our camp because the Twin Otter has just arrived to take us back to Union Glacier base. (Credit: H. Millman)

Returning to the civilisation of Union Glacier was very exciting, especially seeing other people for the first time. I’m usually quite a shy and quiet person, but all reserve vanished in my first hours back on the base as I enthusiastically bounded up to strangers and asked to hear their life stories. The first wash was also fantastic. My hair had been a solid greasy mass of nastiness for weeks and having it back to its fluffy state was a joy. While we waited for a weather window so that the Ilyushin could come and collect us, we sub-sampled our snow/firm core, mended our tents and organised which equipment would be staying in Antarctica and what we’d be taking back. While we were doing this, ALE were starting to pack away Union Glacier base for the winter.

We flew back to Punta on the penultimate Ilyushin of the season, so most of the other passengers were the staff. Everyone was sad to leave, but looking forward to seeing family and friends at home after months away. On returning from Antarctica, even the quiet town of Punta was an assault on the senses. The only smells in Antarctica are cooking, skidoo fumes and the latrine, so when we arrived back the smell of soil and vegetation seemed really strong. It took a few days to readjust to cars, dark nights, proper beds, baths, flushing toilets, running water, central heating, mobile signal, internet, televisions and unlimited electricity. Leaving civilisation was easier than returning to it.

Ice cores waiting for check-in at Punta Arenas airport. We wouldn’t see them again until we landed in Sydney. (Credit: H. Millman)

Our ice cores were stored in a refrigerated lorry back until our flight to Sydney via Santiago and Auckland. Although the cores were in special insulated boxes, the long flight with connections to the heat of a Sydney summer was very stressful. The previous season a box had been left behind at Auckland airport, resulting in a very expensive puddle. This year we were lucky and all boxes arrived at the other end and the unscathed cores were transferred to the freezers at UNSW. Now the hard work begins!

More information:

Project website: http://ellsworthmountains.com/index.html

Short videos from the field can be viewed on Chris Turney’s Vine page:

https://vine.co/u/1021019438360739840

Edited by Sophie Berger and Nanna Karlsson

About Helen Millman:

After completing a BSc in Geography at Swansea University and a Glaciology MSc at Aberystwyth University, Helen moved from her native Devon in south-west England to Australia to start her PhD at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. Her research focuses on modelling Antarctic ice sheet dynamics during the Last Interglacial using data from ice cores, as well as outputs from the CSIRO Mk3L GCM to drive the Potsdam Parallel Ice Sheet Model (PISM-PIK). She is supervised by Chris Fogwill and Chris Turney at UNSW, Steven Phipps at the University of Tasmania and Nick Golledge at Victoria University in Wellington. You can follow Helen on Twitter @helenmillman (https://twitter.com/helenmillman).

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of Week: Blue Ice in East Antarctica

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week — slush on top of sea ice

Pingback: Blue-ice Airfields - Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions

Ruby Metcalfe

Loved this behind‑the‑scenes glimpse of Antarctic fieldwork! ❄️ The way you weave together the humor (hair that hasn’t seen a shower in weeks), the sheer logistics (ice‑melting routines, bucket‑shoveling snow), and the scientific purpose (ice‑cores, seismic testing, bucket‑drilling) paints a vivid, authentic picture. It really captures both the grueling daily grind and the deep sense of discovery that makes polar research so compelling. Kudos for sharing the real-life flavors of field science—brutal, beautiful, and utterly human!