In the morning on the 19th of May, we – the Arctic Circle Traverse 2015 – found ourselves in a great dilemma; to stay or to go? On our check-in conversation with the KISS crew, we were informed that an east front from Kulusuk was expected to hit our location up on the ice sheet sometime in the afternoon. The relatively low winds that we were experiencing would get stronger, and the visibility would reduce even more. The past couple of days at Saddle, we had experienced nothing but strong winds and snow drift. First, it had been a warm front from the west. The next day we were hit by a cold front from southeast. The orientation of our camp did not matter anymore; everything was snowed in. Having completed all our tasks at Saddle, our second-to-last location, we were ready to traverse to Dye-2, our final stop. We had a few more tasks to complete there, before we return to Kangerlussuaq and after a total of three weeks traversing the ice sheet.

The advantages of traversing that day were plenty: We would reach our final destination, while keep being ahead of schedule. Setting camp next to the airway at Dye-2 meant that even if that forecasted east front was to last for days, we would be able once it passes to complete our work, and get off of the ice sheet with the first flight out. Shane and I were also planning to drill one extra firn core about 30 kilometers northeast from Dye-2, and the sooner we reached the old radar station, the better the odds for performing the drilling. Also, Achim’s commercial flight back to Europe was booked for the 26th of May, and missing that was not an option. The disadvantages? Just one really: There was a front coming.

After weighing all the above, we decided to take advantage of this small window of opportunity, and attempt the 100 kilometer traverse. Considering the northeast heading until Dye-2, we would have the frontal activity on our backs. Perhaps we would even arrive there before the storm. We finished with our breakfast and started packing the camp for our last traverse. After about three hours of intense shoveling, disassembling and packing everything on the sleds, we were ready to go.

It was early afternoon when our thumbs hit the throttles of our ski-doos. Everybody made sure to be dressed up warmly. Our outfits had to be as airtight as possible, allowing only a few holes to breathe from. Max was leading our convoy into the fog, with visibility being about 50 meters of field overview. We decided to keep close to one another, with our speed regulated to 25 kilometers per hour. It would take us about 4.5 hours until Dye-2, including two 15-minute stops. Having the wind on our backs made the journey comfortable, enjoyable even. On our first stop for a snack, 30 kilometers in, the enthusiasm was apparent on everyone’s face. So far, so good.

Traversing from EKT (FirnCover project) to NASA-SE (GC-Net) on the 10th of May. Credit: Babis Charalampidis.

Continuing the traverse, I was still riding on the back seat of the “Euro-Ski-Doo”. Achim was always the one to begin a traverse and I would take over halfway through. It was not more than five kilometers since our first stop when I felt a huge wind gust from my right side. And then another. And another. Soon enough, it was just a constant force on my side that I had to struggle against. Max was dragging two sleds with his ski-doo. I could now only see the very last one, just a few meters away.

We kept the pace through the wind, and about 35 kilometers away from our destination, we had the second break. I stopped the ski-doo and smoked a cigarette while the rest had a snack and some water. It looked as if the atmosphere got a bit clearer, giving the illusion that this might have been it. I finished the smoke, grabbed a couple of biscuits, and jumped again on the driver’s seat. Contrary to what we had hoped, the wind got even stronger. Snow storm was now hitting us and the visibility was terrible.

You enter some sort of trance when riding the storm. The reality around you becomes a vail so thick that it minimizes your perception and challenges your comfort zone, but curiously enough without suffocating you. Soon, however – provided the cold is not getting to you – the snow and wind becomes what can only be described as a “white dream”. All you have to or can do is float in it. I found myself being concentrated on small details for prolonged periods, the trembling speedometer, and the sound of the engine or the shallow beam of my headlights. These details become somehow important once there is nothing else out there. I tried to stimulate my thoughts by keeping an eye on Shane and Mike’s sled, whenever I could see it, make sure nothing falls off. It felt almost like waking up when Achim knocked my shoulder. The cold got him. We switched seats again.

Darren pushing forward: Departure from KAN_U (PROMICE network) 6th of May. Credit: Babis Charalampidis.

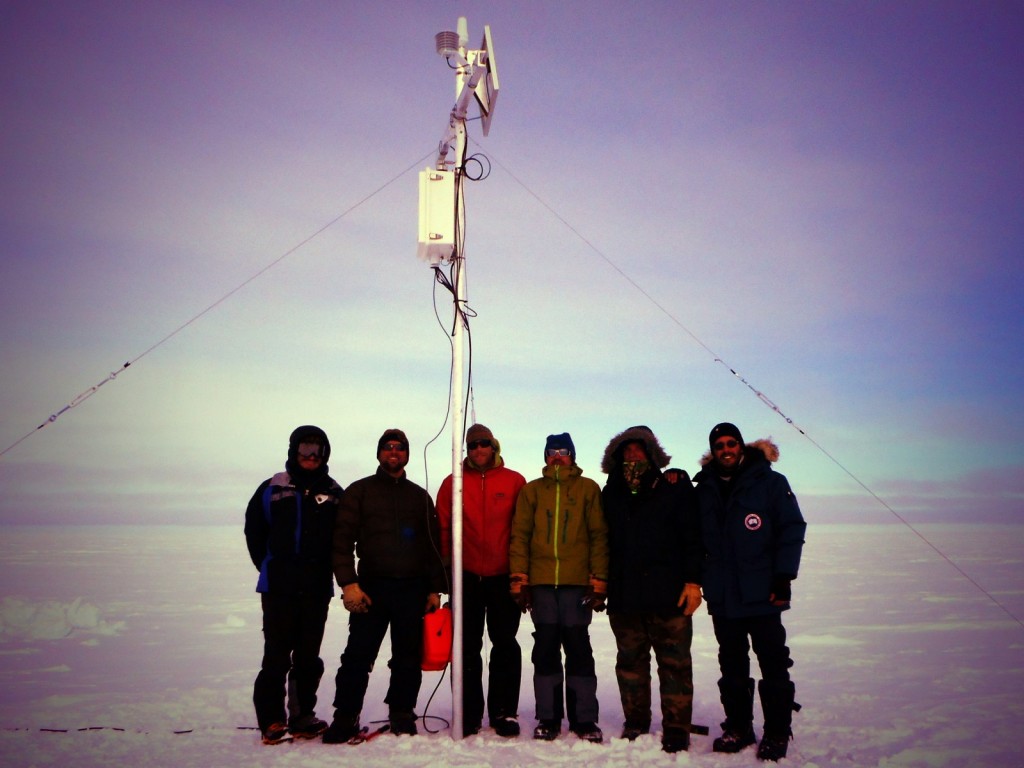

It was not the first time I had arrived at Dye-2, but it was definitely the most peculiar one. This huge construction in the middle of the ice sheet is usually visible from tens of kilometers distance. This time, we were less than two kilometers away and I could not see it. Somewhere inside the distorted from the storm atmosphere, we could see another camp, another group of researchers, possibly. We wasted no time with setting our tents as we were eager to take shelter after the long hours in the storm. The teamwork that had gotten us so far these past two weeks peaked in a remarkable way, with Max leading the efforts. After an hour or so, while finishing with our camp, two researchers from the other camp came to greet us. They were bundled up and wore masks. I recognized one from his eyes, as I had met with him in Kangerlussuaq three weeks before. They said they hoped to catch the next flight out of the ice.

Our stay at Dye-2 was again very successful. All scheduled tasks were completed within 12 hours the second day after our arrival, and we even got to retrieve and log one extra firn core. That day, the other science group departed for Kangerlussuaq. On the evening of the third day, after logging the last core, we were able to relax a bit and visit the old radar station. It felt good to be there again. Shane and Mike managed to enter the side-dome. I was just glad to get to enjoy the view from the top once again.

Setting the last tent – the latrine tent – at Dye-2 on the 20th of May. Credit: Babis Charalampidis.

Back in Kangerlussuaq, we were excited to find ourselves minutes away from a nice, long shower. We got a bit disappointed when Kathy Young told us that the local market was closed – being White Monday and all – and we could not buy beer. She asked us how everything went. We replied that we were really successful, completing more than our scheduled tasks, and that we were really surprised with how smooth everything went finally. We definitely had favorable weather most of the time, and we managed to take advantage of it. She laughed a bit, and said that we definitely impressed with our performance. We didn’t get it, and then she explained that the other science group from Dye-2 kept talking about our arrival in the middle of the storm and our casual camp establishment, like there’s nothing going on, while they had been in the tents due to the weather for days. We felt quite flattered by that, however we didn’t really have a choice. It didn’t feel casual either.

Two days later, we were on the move again, this time with an icelandic Twin Otter, visiting for one more week the northern locations of the FirnCover project. We established the remaining firn compaction stations, and retrieved several more firn cores. Favorable weather conditions were instrumental for the success of this year’s Arctic Circle Traverse. After all, that’s the most important factor up on the ice sheet. A skillful team, with which you can always push some more is the other. I am glad I was one sixth of it.

Edited by Nanna Karlsson and Sophie Berger

Babis Charalampidis (GEUS/Uppsala University) is an Uppsala University PhD student within the SVALI project, based at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland and supervised by Dirk van As. He is interested in the Greenland ice sheet’s mass budget, particularly the link between energy balance and subsurface processes such as percolation and refreezing. He studies the changes of the lower accumulation area of the southwest of the ice sheet in a warming climate, based on in situ observations.

Read Babis’s story of his fieldwork last year here.