19 November 2014, the Iliuchine 76 gently lands on the runway of the Russian Antarctic station, Novolazarevskaya, in Dronning Maud Land. For the first time, I’m in Antarctica! It is 4 o’clock in the morning and we need to hurriedly offload 2 tons of material intended for our field mission near the Belgian Princess Elisabeth Station. I’m deeply impressed by the landscape although it is dotted with containers, people and machines. I am impressed by the fuzz. I am impressed by the novelty. I am impressed by the icescape. It is cold, but I don’t feel it.

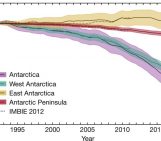

I take part in an expedition lasting five weeks and led by the Laboratoire de Glaciologie of the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) in the framework of the Icecon project.The project aims at constraining past and current mass changes of the Antarctic ice sheet in the coastal area of Dronning Maud Land (East Antarctica) to better understand past and present ice volumes and the extension of the Antarctic ice sheet across the continental shelf during the last glacial period. This year we are a team of 5 to do the job: GPS measurements, ice-core drilling, high- and low-frequency radar measurements (GSSI and ApRES), televiewer measurements … The ApRES radar is a new phase-sensitive radar developed by British Antarctic Survey (BAS), capable of detecting internal structures in the ice and changes in the position of internal layering over time.

After a couple of hours at the Russian base, it’s time to fly to the Princess Elisabeth Station (the Belgium base, PEA). The arrival in a Bassler (a former DC3 re-equipped with turbo-props) with stunning views of the Sor Rondane Mountains and the Princess Elisabeth station on the Utsteinen rim is simply magnificent. Alain Hubert, the base manager, gives us the first security rules and shows us the different parts of the base.

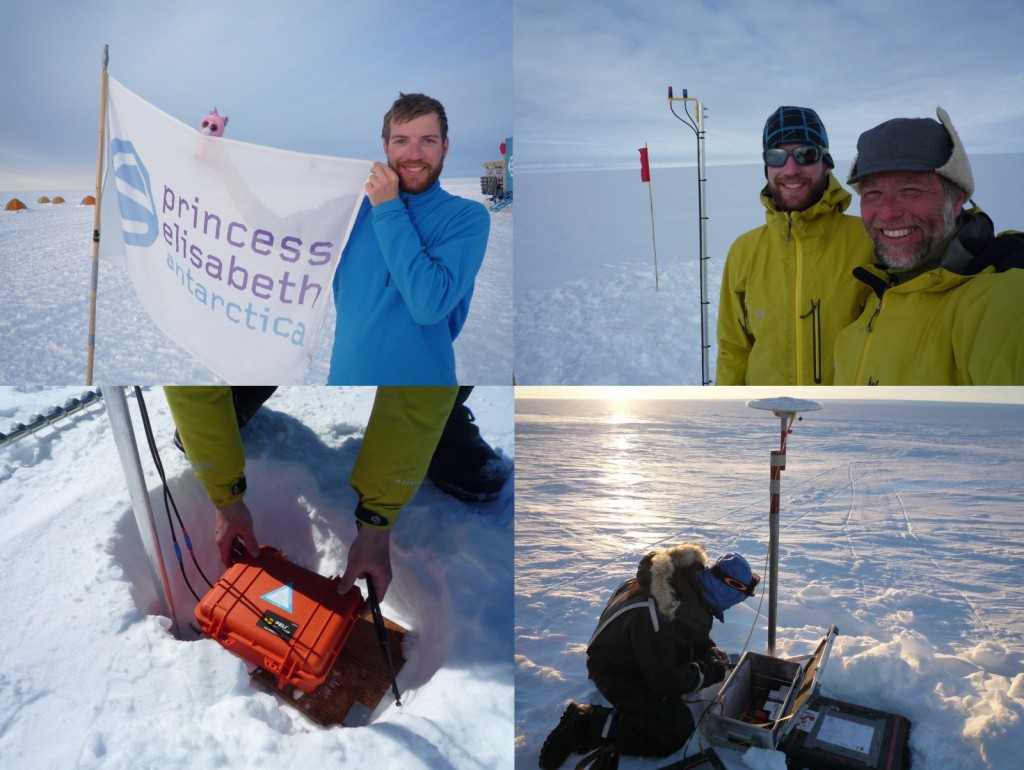

After following the various field training and especially an exercise that aims at pulling yourself out of crevasses, it’s time to inspect, to set up, and to test our equipment. While one part of the team sets up the drill, Frank Pattyn and I test the GPS and radar equipment, mainly the ApRES that is a new “toy” for us. The first results are promising, we can clearly identify the bed topography and internal layers. The two GPS systems sponsored by the “10km of the ULB”, a run organised by the students of our Faculty, are also tested next to the L1L2 GPS systems for precise positioning. As our departure is imminent, I’m excited (even though my level of Coca-cola are getting low – I ‘m an avid consumer of this “evil drink” and Frank was afraid that I wouldn’t survive without sufficient sugar intake).

On 27 November, we leave PEA in the evening for one night and one day across the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf to Derwael ice rise. We are 6 scientists, 2 field guides and 1 technician. After 25 hours of travel, we set up the camp on the top of the divide. We start immediately with the radar measurements to locate potential drill sites. However, we get caught in a storm the following day and as Frank says “not a nice one”.

The snow drift is just amazing and the atmospheric pressure drops frighteningly (“can this still go lower?”). The whiteboard installed in the living container is not wide enough to draw the graph of pressure change, nor is it high enough to accommodate the lowest values. Furthermore, it’s quite warm, meaning that snow melts in contact with persons and goods. Despite efforts of everyone to clear away the snow, we leave our tents and sleep in the containers for 2 days. Not the most comfortable nights, because we share a two-bunk space with three people, and despite a container it remains very shaky! After three days of amazing experience, we clean up the camp and the science restarts. For one week Frank and I perform radar and GPS measurements in a 10km radius around the camp. These measurements will be repeated in 2015-2016 to provide new data on ice compaction, density and flow. While Frank thoroughly checks the collected data, I have some time to get familiar with the drill, which should prove to be very useful thereafter. The “drill part” led by Jean-Louis Tison and Morgane Philippe aims at drilling two 30 m deep ice cores on Derwael Ice Rise, 2 km on each side of the divide. We want to investigate the spatial variability of snow accumulation induced by this ice rise that sticks approximately 300 m above the surrounding flat ice shelf and therefore perturbs the surface mass balance distribution (Lenaerts et al., 2014).

I use this week to improve my knowledge on other scientific techniques, such as the coffee-can method (will complement the results from the ApRES) or geodetic GPS measurements with Nicolas Bergeot. I also learn the basics of snowmobile mechanics (it’s surprising to see the amount of snow that can be put in an engine!). Unfortunately we get stuck for another 2 days by a new storm event. We use this time to have a look on the first radar profiles and to prepare the second part of the expedition.

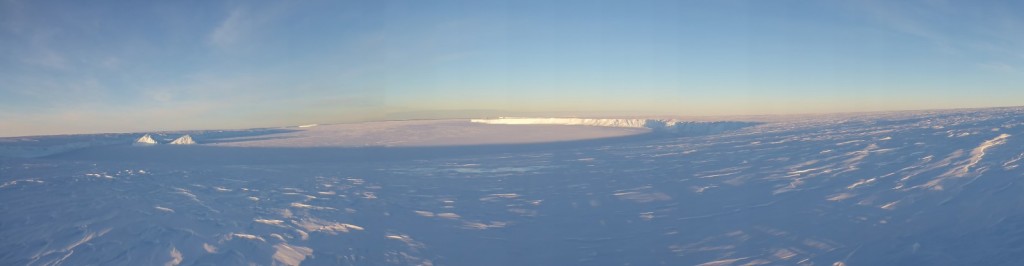

On 9 December, we leave the camp on Derwael ice rise and move towards the Roi Baudouin Ice Shelf, 40km to the west. We set up the camp in a longitudinal depression (like a trench) on the ice shelf that stretches from the grounding line to the coast.

The purpose of this part of the field work is twofold: first of all, determine the mass budget of ice shelves. To do that, we need to map carefully the flow speed of the ice-shelf. Secondly, understand the formation of the trench in evaluating if under the ice-shelf, the ice is melting or accreting (formation of marine ice) and analyze the surface melt history by investigating near-surface melt layers.

The first three days are devoted to make radar measurements (ApRES) in the center and on the sides of the trench. The thickness of ice and the reflection at the interface with the ocean is different from the one on the ice rise; we take some time to develop a robust method and determine the best settings of the radar. Together with Frank Pattyn and Jan Lenaerts (InBev Baillet Latour fellowship, http://benemelt.blogspot.be/) I perform a 120km transect with a high-frequency radar towed by a snowmobile to map the near-surface internal structure along the ice shelf and link the drill site with the grounding zone. Driving at 8 km per hour for 8 hours a day, it’s an opportunity for me to think about how lucky I am to be here. Alone in the vastness of the Roi Baudouin ice-shelf, I feel very small. Back in camp, we find out that the drill got stuck at a depth of 54m in the borehole and preparations to free the drill are on their way. During this time I carry out a number of high-frequency radar measurements with Alain Hubert (the base manager) to fine-tune the equipment to potentially detect crevasses near the surface. To our surprise, we stumble upon a crevasse more than 500m long, 10m wide and 20m high. Moreover, we can safely descend through the apex of the crevasse to discover its vastness. Truly a magic moment!

Thirty-six hours later, and thanks to antifreeze, the drill restarts. This small technical incident pushes us to work the next couple of days through the day and the night (under the sun at 3am is rather special) and we take turns in operating the drill. We reach a depth of 107m, not far from the 155 meters needed to reach the bottom of the ice shelf, but the brittle ice makes progress very difficult. Nevertheless, this is the third core of the (short) season, and as valuable as the previous ones. We can clearly identify every single ice layer over 200 years as well as the surface melting history.

Before leaving back to the base, we finish the installation of the famous Tweetin’IceShelf project (http://tweetiniceshelf.blogspot.com); a project also presented at the EGU General Assembly in 2015. We deploy two GPSes on the flanks of the trench and one in the center. These are simple GPS systems that record their position every hour. They are named GPS CGEO (from Cercle de Géographie et de Géologie de l’ULB) and GPS CdS (from Cercle des Sciences). In the center of the trench, the ApRES is installed which measures once a day the radar signal through the ice. All systems will be effective throughout the Antarctic winter. Data are sent via Twitter to be followed by a larger community. Just follow the @TweetinIceShelf on Twitter. You will not be disappointed.

It’s time to go back to the station, which is reached after 20 hours of travel across the ice shelf and the coastal ice sheet. Over 2 days we will be at Cape Town and we have to clean up everything for the next field season.

I know it is my first time to Antarctica, and as most first-timers, an unforgettable experience of vastness, whiteness, silence, laughter, hard work and fun. When I board the plane I feel delighted and fulfilled and ready to find back green landscapes and city soundscapes in less than ten hours.

The text is based on the blog that was held during the mission: http://icecon2012.blogspot.be/

Edited by Sophie Berger

Brice Van Liefferinge is a PhD student and a teaching assistant at the Laboratoire de Glaciology, Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium. His research focuses on the basal conditions of the ice sheets.

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week — Happy New Year

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | ©LEt’sGO to Antarctica !