Post by Scott Jasechko, Assistant Professor of Water Resources with the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management, at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and by Debra Perrone, non-resident Fellow at Water in the West and an Assistant Professor, also at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in the United States.

_______________________________________________

In December, 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency finalized a report [Ref. 1] on hydraulic fracturing and drinking water resources that, among other conclusions, states:

(a) Quote from [Ref. 1]: “scientific evidence that hydraulic fracturing activities can impact drinking water resources under some circumstances”

(b) Quote from [Ref. 1]: “When hydraulically fractured oil and gas production wells are located near or within drinking water resources, there is a greater potential for activities in the hydraulic fracturing water cycle to impact those resources.”

Tens-of-millions of Americans rely on groundwater stored in aquifers for drinking water. Because it is possible that hydraulic fracturing activities can impact water resources (i.e., quote (a) above), and because groundwaters located close to hydraulic fracturing activities are more likely to be impacted than those farther away should a contamination event occur (i.e., quote (b) above), it is important to assess how many domestic groundwater wells are located close to hydraulically fractured wells.

In a recent study [Ref. 2], we assessed how close domestic groundwater wells are to hydraulically fractured wells, and to oil and gas wells (some hydraulically fractured, some not). Due to consistencies limitations in both oil and gas and groundwater well datasets, we limited our analysis to groundwater wells constructed between 2000-2014, hydraulically fractured wells likely stimulated during the year 2014, and oil and gas wells producing in 2014.

Our study has two main findings.

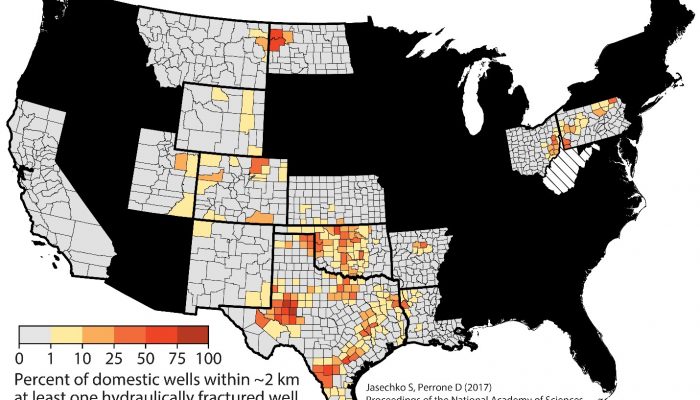

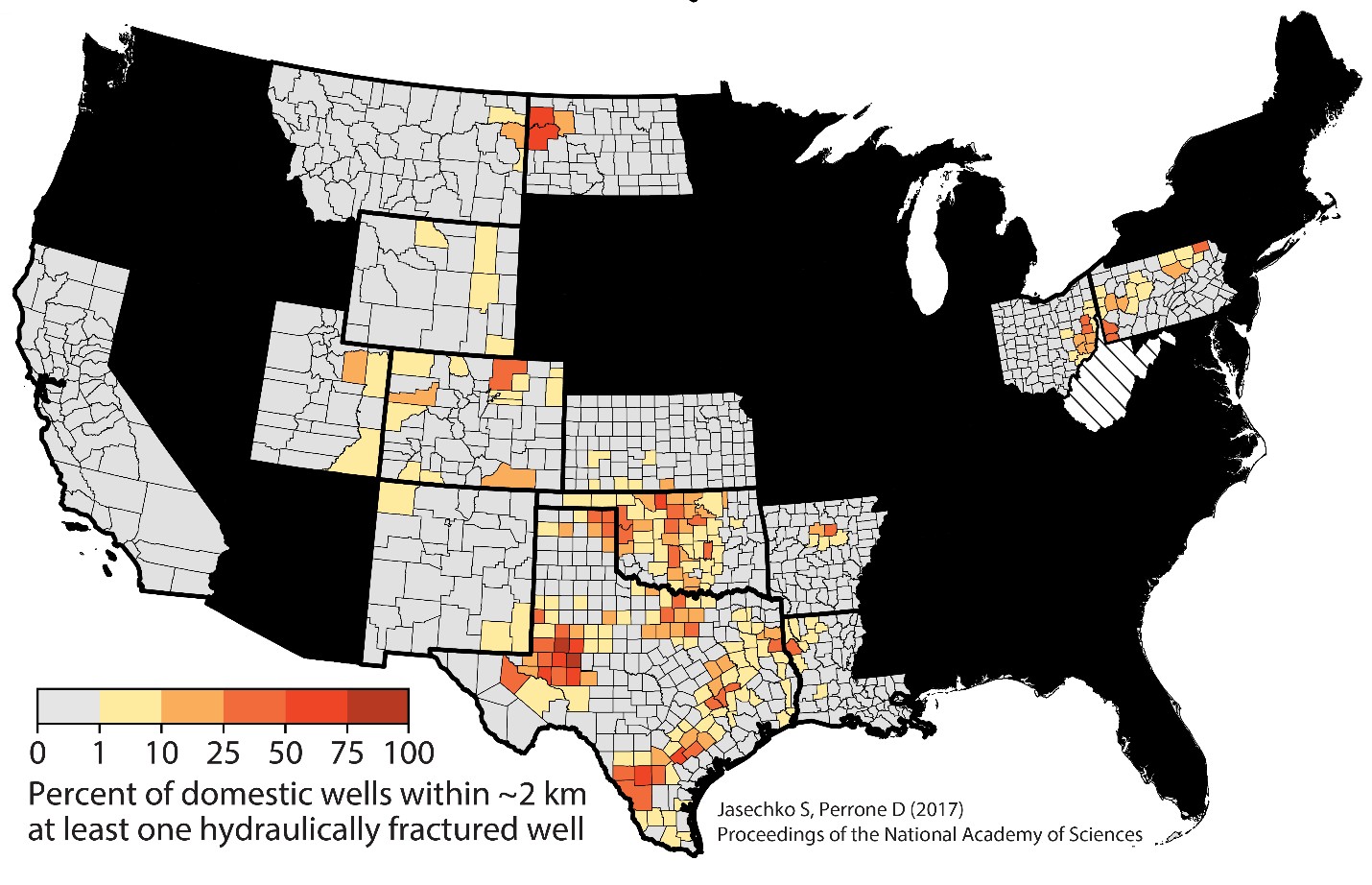

First, we found that most (>50 %) recorded domestic groundwater wells constructed between 2000 and 2014 exist within 2 km of at least one hydraulically fractured well in 11 US counties (Fig. 1). Further, about half of all recorded hydraulically fractured wells that were stimulated during 2014 are located within 2-3 km of at least one domestic groundwater well. We suggest these regions where groundwater wells are frequently located near hydraulically fractured wells might be suitable areas to focus limited resources for further water quality monitoring.

Figure 1. The percentage of domestic groundwater wells that were constructed between 2000 and 2014 that have a recorded location that lies within a 2 km radius of the recorded location of at least one hydraulically fractured well that was stimulated during the year 2014.

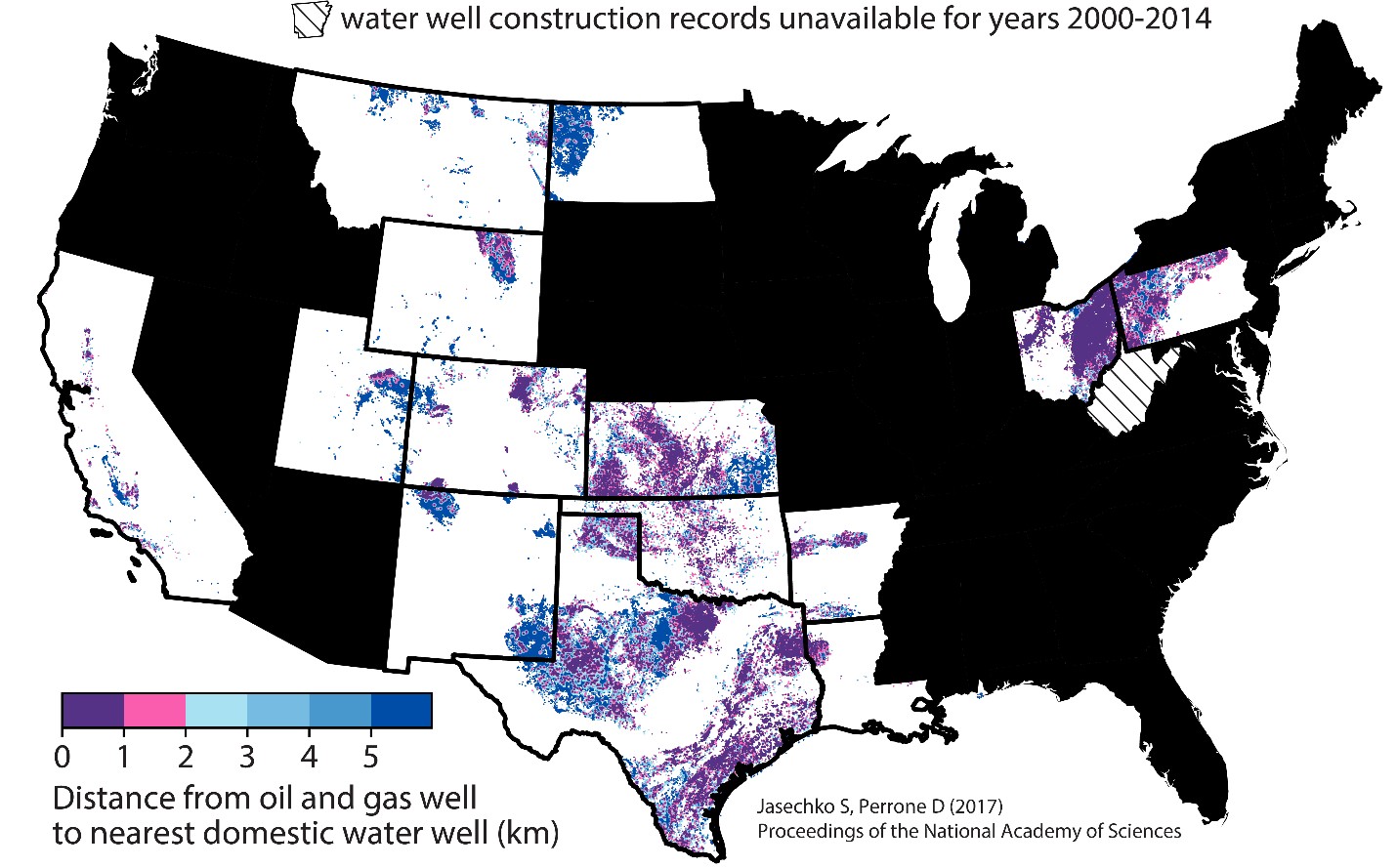

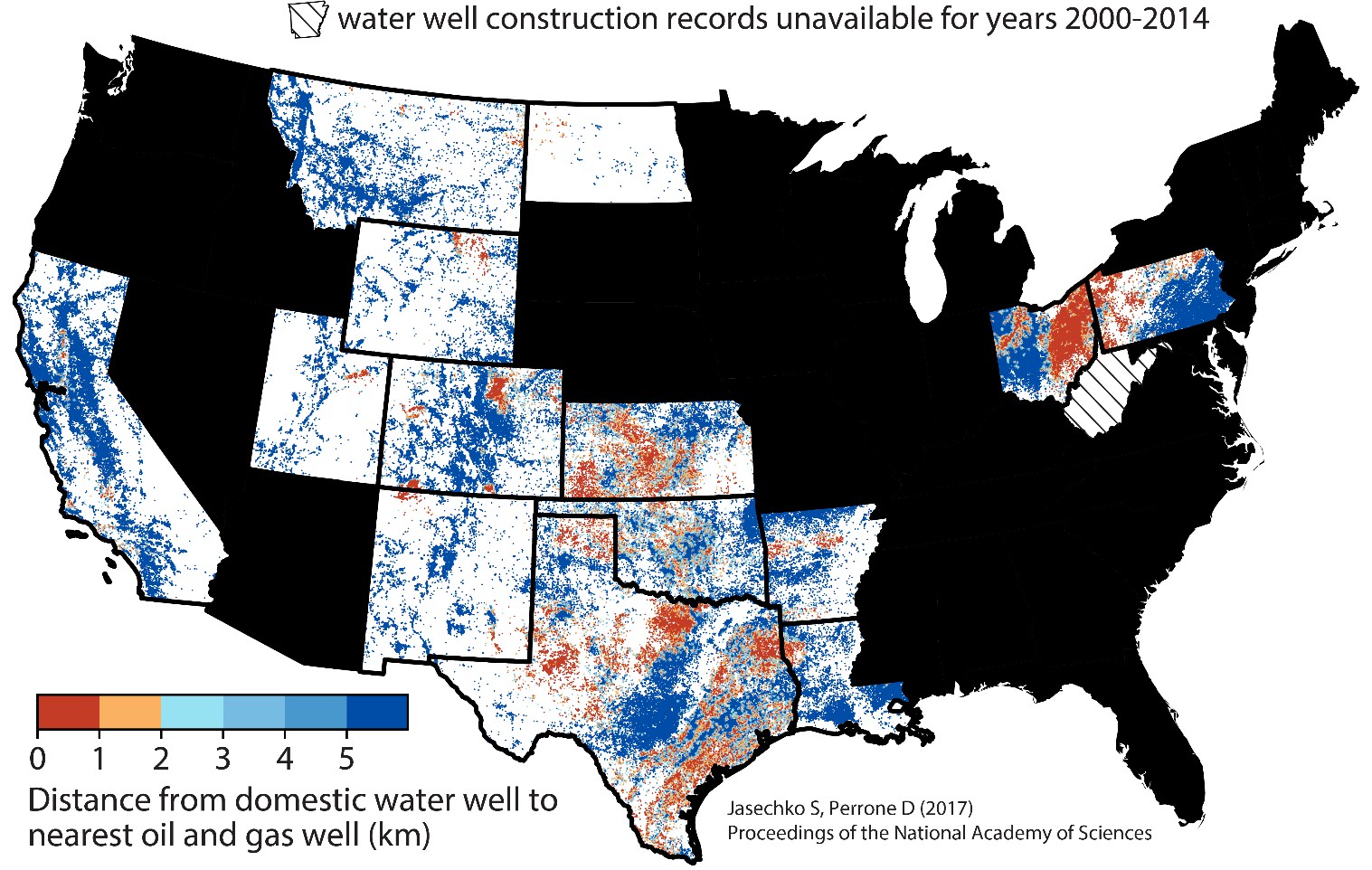

Second, we assessed the proximity of oil and gas wells being produced in 2014 – some hydraulically fractured but others not – and groundwater wells. We found that many domestic groundwater wells are located nearby (<1-2 km) at least one oil and gas well, and, that actively-producing oil and gas wells are frequently located nearby at least one domestic groundwater well (Figure 2). Many of the potential contamination mechanisms associated with the construction, stimulation and use of hydraulically fractured wells are also associated with conventional oil and gas wells, including potential for spills on the land surface and well integrity failures [Ref. 3]. Therefore, assessing potential water quality impacts resulting from activities associated with oil and gas production derived from both hydraulically fractured wells and from conventional oil and gas wells is important.

Figure 2. The upper panel shows the distance between recorded oil and gas wells producing in 2014, and recorded domestic groundwater wells constructed between 2000 and 2014. The lower panel shows the distance between recorded domestic groundwater wells constructed between 2000 and 2014 and the nearest recorded oil and gas wells producing in 2014 (see Ref. [2] and references therein for data sources).

We conclude that (i) publicly-available groundwater well construction data are critical for managing groundwater resources and completing water quality risk assessments (see Ref. 4 for data quality information), and emphasize that not all states currently provide access to digitized groundwater well construction records (e.g., Figure 2), (ii) hotspots exist where activities related to oil and gas production occur nearby domestic groundwater wells, and these regions may be targeted for further groundwater quality monitoring, and (iii) assessing how frequently activities in the hydraulic fracturing water cycle impact groundwater quality may be vital to securing high quality water pumped from many domestic water wells where oil and gas production is common.

Figure 3. Hydraulically fractured well situated close to an irrigation system in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

_______________________________________________

References:

[Ref. 1] U.S EPA. Hydraulic Fracturing for Oil and Gas: Impacts from the Hydraulic Fracturing Water Cycle on Drinking Water Resources in the United States (Final Report). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, EPA/600/R-16/236F, 2016. Accessed from https://www.epa.gov/hfstudy November 15, 2017.

[Ref. 2] Jasechko S., Perrone D. (2017). Hydraulic fracturing near domestic groundwater wells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

[Ref. 3] Vengosh A., Jackson R. B., Warner N., Darrah T. H., Kondash A. (2014). A critical review of the risks to water resources from unconventional shale gas development and hydraulic fracturing in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology 48, 8334-8348.

[Ref. 4] Perrone D., Jasechko S. (2017). Dry groundwater wells in the western United States. Environmental Research Letters 12, 104002.

_______________________________________________

Scott Jasechko’s research focuses on fresh water resources, and uses large datasets to understand how rain and snow transform into river water and groundwater resources.

Scott Jasechko’s research focuses on fresh water resources, and uses large datasets to understand how rain and snow transform into river water and groundwater resources.

Find out more about Scott’s research at : http://www.isohydro.ca.

Debra Perrone is interested in the multifaceted interrelationship between water, energy, and food resources. Her research explores how the interactions among these resources affect decisions and tradeoffs involved in water resource management.

Debra Perrone is interested in the multifaceted interrelationship between water, energy, and food resources. Her research explores how the interactions among these resources affect decisions and tradeoffs involved in water resource management.

Find out more about Debra’s research at: http://debraperrone.weebly.com/.