Ever since I was eight and fascinated by how rocks were formed, I dreamed of being a geoscientist. Growing up in Nigeria, I was captivated by rocks as nature’s storytellers—from how rivers shaped our landscapes to how oil could be extracted from deep beneath the Earth. This passion fueled my ambition to become a geoscientist as I pursued my bachelor’s, master’s, and eventually my PhD. However, along the way—from earning my degrees to becoming a research fellow—I had to navigate more than just science; I encountered barriers that still exist for Black women in geoscience today. Throughout my journey, I’ve been fortunate to find allies, mentors, and friends who recognized my dedication and believed in my abilities. Their encouragement, sponsorship, and support were crucial lifelines when I faced systemic barriers at the beginning of my career.

One particularly eye-opening experience that revealed just how deep these barriers run was the shocking reality of receiving countless job application rejections simply because of my non-English name. After submitting hundreds of job applications under my name, Munira Raji, the rejections piled up. As an experiment, I began applying for the same positions using an English name, and surprisingly, I started receiving invitations for interviews despite having the same credentials. This stark contrast illustrated that talent and qualifications aren’t always enough to overcome ingrained biases, and the systemic barriers faced by people like me, such as unconscious bias, continue to cloud hiring and promotions, undervaluing our achievements.

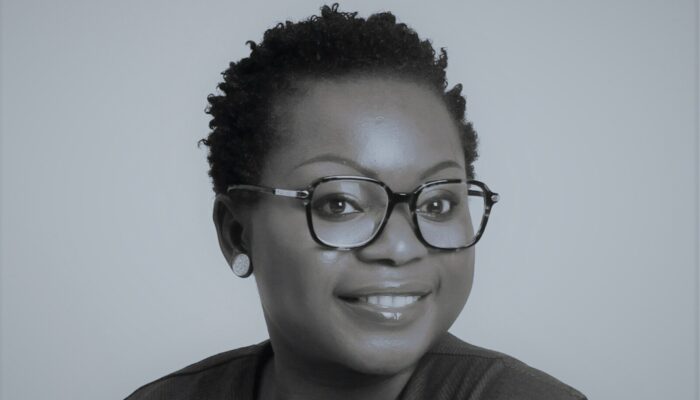

Today, as a Sustainable Geoscience and Science Diplomacy Research Fellow at the University of Plymouth in the UK, I still find myself in a discipline where faces like mine and the representation of individuals from minority backgrounds—especially Black women—in leadership roles remain scarce. This lack of diversity often makes it difficult for young Black girls and women to envision their future in geoscience, as they struggle to find role models who reflect their own identities and experiences.

The power of diversity in Geoscience

My personal experiences have shown me how transformative an inclusive geoscience community can be. Last year, I collaborated with scientists from five different continents on a climate change impact project. The diversity of perspectives led us to solutions we might never have considered with a more homogeneous team. Working at the interface between geoscience and diplomacy, I’ve seen firsthand how different viewpoints can tackle seemingly impossible problems related to climate change, water scarcity, resource depletion, and energy poverty. Everyone brings a distinct background and perspective to the table, enriching our collective understanding and fostering a more innovative approach to solving global challenges. These experiences drive my passion for creating inclusive spaces within geoscience. When I mentor students from minority backgrounds, I see how their unique perspectives enrich our field and propel us toward more innovative solutions.

Celebrating progress while acknowledging the journey ahead

In recent years, I’ve witnessed encouraging changes within UK geoscience. While gradual, these changes fill me with hope. I’ve participated in several initiatives at UK universities and geoscience organizations aimed at improving diversity and inclusion within our field. Still, one program stands particularly close to my heart—the Equator Research Group. When I think back to the summer of 2022, I remember the nervous energy and excitement as we launched the first Equator Research School. As one of the organizers, I saw firsthand how powerful structured training can be. The program goes beyond traditional academic training; we created specialized workshops and training sessions focused on networking, science communication, academic publishing, public profiles, visibility, PhD applications, CV building, mock interviews, presentation skills, and one-on-one mentoring. We actively worked to dismantle the systemic barriers that often hold talented, underrepresented students back from pursuing research careers in Geography, Earth, and Environmental Sciences (GEES).

My heart swells every time I open LinkedIn these days. I see posts from students who were part of our first cohort—students from underrepresented minority groups who, just like me years ago, needed someone to believe in them and show them the way forward. They’re not just surviving in academia; they’re thriving—securing competitive internships, landing impressive jobs, and building valuable professional networks. One student recently messaged me about landing her dream job, saying our mock interview sessions gave her the confidence she needed. Another is mentoring younger students, creating a beautiful ripple effect of support and encouragement. This kind of progress—tangible, measurable, and deeply personal—is something I hadn’t witnessed in my field for a long time. It reminds me that while change can be slow, it is possible when we create intentional spaces for growth and support. Each success story from our Equator participants feels like a personal victory—a small but significant step toward the more inclusive geoscience community I’ve always envisioned.

Confronting ongoing challenges

In my day-to-day work, I still encounter unconscious bias within the geoscience community at the university. In meetings, I still face questioning looks and often have to justify my presence, as if my qualifications and expertise aren’t enough to warrant my seat at the table. Throughout my academic journey—earning three geology degrees at different UK universities—I never saw myself reflected in the faculty; not a single Black or Brown lecturer or academic. The statistics speak volumes: in the entire UK, there is only one Black male professor of geology who now works in the industry. A particularly painful memory from my first Vice Chancellor’s meeting for academic staff stands out. I queued up with my colleagues for refreshments during the tea break, reaching for a shortbread biscuit. The University caterer stopped me, insisting these refreshments were “for staff only.” When I explained that I was indeed staff, she demanded to see my staff ID badge, which I didn’t have with me. As I glanced around for a familiar face who could verify my position, the stark reality hit me: I was the only non-White academic in the room. Rather than continue to defend my right to a 50-pence biscuit, I left my tea and dignity behind and returned to my office. While trying to explain this incident to a colleague, I burst into tears, describing how people like me often face systematic racism. Since that experience, I’ve made it a point to bring my own refreshments for breaks during any campus meeting—a small but necessary step to protect myself from similar humiliation.

This isolation takes its toll but also fuels my determination to create change. It breaks my heart to watch promising Black geoscience students drift away from the field, discouraged by the same sense of not belonging that I combat daily. Without visible role models in lectureships or leadership positions, many struggle to envision a future for themselves in academia.

Looking to the future

My journey has evolved far beyond studying rocks—though that eight-year-old girl’s fascination with geology still burns bright. Today, as a Sustainable Geoscience and Science Diplomacy Research Fellow, I work on international collaborations and engage in EDI efforts to transform our field from the inside out. I believe in the power of personal stories and open dialogue about race and inclusion in academia. When I speak to young Black students interested in geoscience, I share my struggles and successes, showing them that while the path may be challenging, it is increasingly possible to thrive. When a young Black student recently told me, “I never knew someone who looked like me could be a geoscientist,” it reinforced why visibility matters. But stories alone aren’t enough; we need concrete, systematic change. I actively advocate for diverse applicants for funded PhD and hiring panels for staff at my institution.

To my colleagues in the geoscience community: we need more than passive support. Active advocacy for inclusive practices, speaking up against inequity, mentoring students from diverse backgrounds, and pushing for institutional change are essential. Education and awareness are just the beginning; we need concrete action to transform our field. I envision a future where no student questions their place in geoscience because of their race or background, where no student feels the need to change their name to secure an interview. This is the future I’m working to build—one small change at a time. Will you join me?

Ini Inyang

Great write-up Munira!

This is so familiar with my experience since I concluded my BSc in Geology. Despite the passion for geology and going on to an MSc in Environment Health and Safety, it’s still been an almost impossible task in progressing from there.

Feels good to know my experience is not an isolated one. Kudos on your resilience and progress.

Would like some advice on how to forge ahead professionally.