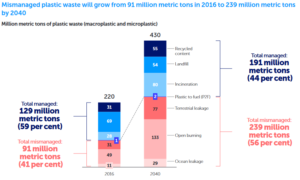

It appears that plastics have well and truly invaded even our most inaccessible environments: the deepest point in the ocean (the Mariana trench) and the highest mountain peak in the world (Mt. Everest) both contain pieces of plastic from human activities miles away. With plastic waste flowing into aquatic ecosystems expected to nearly triple by 2040, it is safe to say that nature is in “emergency mode.”

This June 5th marks five decades since the first World Environment Day was observed, which according to the United Nations, is the largest global platform for environmental public outreach. Every year, the UN draws attention to different issues that threaten the environment, and this year’s focus – with good reason – is plastic pollution.

Plastic pollution: a toxic ripple effect

The harmful impacts of plastic pollution range from environmental degradation to economic losses for industries and communities, to serious risks to marine and human health. And its link to climate change is often ignored; increased plastic production requires an increased use of fossil fuel, and plastic products generate greenhouse gas emissions throughout their lifecycle.

There are also the lesser known “indirect effects” of plastic pollution: a 2021 study on marine plastics pollution showed that the four coastal ecosystems that store the most carbon and act as barriers against rising seas and storms – mangroves, seagrasses, salt marshes and coral reefs – are being put under increasing pressure from land-based plastics as a result of their proximity to rivers.

A system-wide problem demands system-wide change

In the last few years, several national and local interventions have been introduced to reduce plastic flow into the ocean. This includes national bans on single-use plastics, community clean-ups and business commitments to reduce, redesign and reuse plastics. But these measures are only estimated to reduce annual plastic flows to the ocean by 7%. Does this mean that present efforts fall short, aren’t doing what they should, or that we are simply looking at mitigation strategies all wrong?

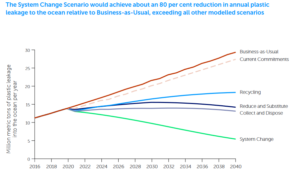

A 2020 report offers hope: it reveals that we can indeed reduce the amount of plastic entering the ocean by 80% in the next 20 years if we turn to existing technologies and solutions. The report, led by The Pew Charitable Trusts and supported by University of Oxford and University of Leeds, among other thought partners, goes on to state that single-solution strategies cannot stop the plastic pollution problem.

The group modelled three single-solution scenarios that focused on implementing either upstream or downstream measures—the Collect and Dispose Scenario, the Recycling Scenario, and the Reduce and Substitute Scenario. Interestingly, they found that the System Change Scenario produced superior results across economic, environmental, and social dimensions, compared to the three single-solution scenarios. Any of the single-solution strategy approaches hit technical, economic, environmental, and/or social limits. This makes sense if you think about it: a system-wide problem demands system-wide change.

The above graphic shows expected levels of plastic leakage into the ocean over time across different scenarios. It shows that although upstream-focused pathways (Reduce and Substitute Scenario) and downstream-focused pathways (Collect and Dispose Scenario and Recycling Scenario) reduce annual leakage rates relative to “Business as Usual”, they do not reduce leakage below 2016 levels. Only the integrated upstream-and-downstream scenario (System Change Scenario) can significantly reduce leakage levels.

How can geoscientists weigh in on the plastic crisis?

Geoscientists are uniquely placed to investigate solutions that curb plastic pollution in this regard, owing to their unique and multi-disciplinary perspective on the biosphere and hydrosphere, their understanding of the nuances of seafloor composition, their capacity to record the downstream effects of any plastic mitigation efforts, and their ability to predict the long-term fate of plastic waste in the geological system.

As the authors of a 2021 Geology paper say, geoscientists truly understand “the transient nature of the stratigraphic record and its surprising preservation, and the unique geochemical environments found in deep-sea sediments. [Geoscience’s] source-to-sink approach to elucidate land-to-sea linkages can identify the sources and pathways that plastics take while traversing natural habitats and identify the context in which they are ultimately sequestered, and the ecosystems they affect. This will happen by working closely with oceanographers, biologists, chemists, and others tackling the global pollution problem.”

As with many environmental questions that humanity is facing in the current era, geoscience as a subject has long been seen as more of a bystander in the quest for solutions, with many in the public sphere not always recognising the role that geoscientists have to play. But if there is anything that has been revealed in recent years it is that researchers agree that mitigation efforts targeting plastics in all environments lack insights from the geosciences, and will greatly benefit from a broader range of disciplines working together to inspire systemic changes. Instead of being a bystander, it is becoming clearer and clearer that geoscientists will play a critical role in providing specialised, systemic solutions for the global plastic pollution problem.

What other ideas, perspectives, techniques or solutions do you think geoscientists can offer? Let us know in the comments below!