Until recently, scientists assumed lightning had a homogeneous distribution of energy inside its channel. But researchers like Damien Bestard, a PhD student with the Sorbonne Université have found that the composition of each bolt is quite variable.

Bestard presented his findings at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly EGU23 on Monday (April 24).

As part of his research, Bestard measures thunder with microphones and breaks down each lightning strike into separate components of acoustic pressure, which he measures in units of pascal. The team has collected acoustic recordings of thunder for the past decade, as part of the HyMeX project, during field campaigns carried out with the support of the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA).

“For us, lightning is like many tiny sparks stuck together, and each one emits its own wave,” said Bestard in conversation with EGU’s communications team.

You’re probably familiar with the trick of counting the number of seconds between a lightning flash and the sound of thunder to find out how far away lightning is from where you are. Thunder acousticians such as Bestard rely on the same principle to locate lightning, but use a microphone array and electromagnetic detection systems instead of ears and eyes. The technical term for this is acoustical reconstruction.

“I talk about the intercorrelation of signals from an array like three or four people standing in a pool who can’t see, ” said Bestard. “If someone were to throw a rock into the pool, they might not know exactly where it fell, but they would feel the wave at the surface of the water. And if everyone tells each other when they feel the wave, it is possible to deduce where it was coming from.”

Like a rock falling into a pool, which gives off circular ripples in the water it falls into, thunder generated by lightning generates acoustical spherical waves.

“The time that we receive these waves gives us the distance propagation,” said Bestard. “So with angle and distance, we have the source point [of the strike] in 3D.”

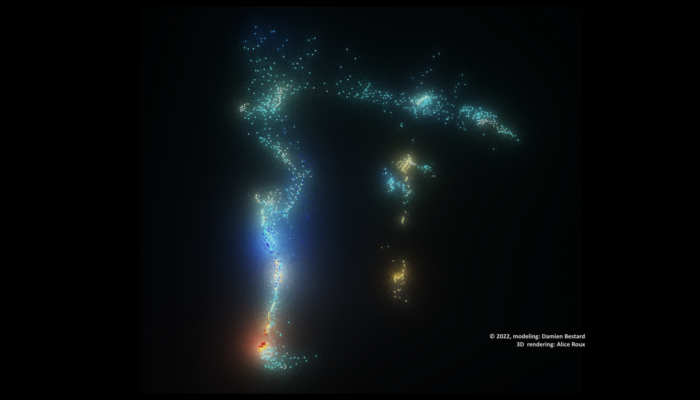

In his presentation at the General Assembly, Bestard showed a 3D reconstruction of a bolt of lightning made from black dots. Each represents an acoustical source, or a tiny lightning emitting its own thunder.

“Each little tiny time interval of signals corresponds to a spot on the lightning,” said Bestard, explaining that the intensity of the sound and the direction of the received plane wave vary significantly all along the channel.

“In other acoustical research it was supposed to be quite a homogenous distribution, but in our work we showed that it can be totally heterogeneous. While lightning can be as long as 10 kilometres, half of the total power can be concentrated in a section of a couple hundred metres.”

Why? Bestard says this is yet to be understood.

Determining the structure of lightning has increasingly become a focus of interest for thunder acousticians. There is currently no complete physical model of lightning, and researchers believe understanding lightning composition and structure will help.

“There is much active research about the integration of electrical parameters to weather forecasting,” Bestard said.

Researchers believe climate change may be causing differences to the form and frequency of lightning, from slower, lingering strikes (known as continuing electrical currents) that are more likely to cause forest fires, to a 41% global increase in lightning flash events by 2090.

For acousticians, these changes add to the urgency and importance of their work. For more information on this study or the future of lightning research, you can speak to Bestard via EGU’s media team (media@egu.eu).