In this month’s GeoEd column, Sam Illingworth tells us about how teaching undergraduate students about peer review can help eliminate bad practice.

To anybody other than a researcher, the words peer review might seem like a fancy new age management technique, but to scientists it is either the last bastion of defence against the dark arts or an unnecessary evil that purports to ruin our greatest and most significant works.

According to Wikipedia (itself a fine proponent), peer review is defined as “the evaluation of work by one or more people of similar competence to the producers of the work (peers). It constitutes a form of self-regulation by qualified members of a profession within the relevant field.”

Peer review itself is not a new concept; the first documented description of a peer-review process, being found in the ‘Ethics of the Physician’ by Ishap bin Ali Al Rahwi (854–931), states that the notes of physicians were examined by their contemporaries to assess if treatment had been performed according to the expected standards (you can read more on the history of the peer-review process in this article).

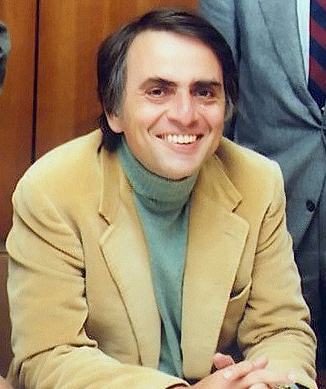

Even the great Carl Sagan found the critique of his work difficult to stomach (Photo credit: NASA JPL, via Wikimedia Commons).

“Why do we put up with it? Do we like to be criticized? No, no scientist enjoys it.” So sayeth American cosmologist and author Carl Sagan about the ‘joys’ of peer review, in his book ‘The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark.’ He goes on to say that “Every scientist feels a proprietary affection for his or her ideas and findings. Even so… the hard but just rule is that if the ideas don’t work, you must throw them away.”

Just reading these words brings me out in the kind of cold sweat that I normally associate with seeing the bill from mechanic, after having your car serviced. You know that you are going to have to bite the bullet, but in your heart of hearts you just wish that it weren’t so.

Love it or loathe it the peer-review system is an integral part of being a researcher, and given its prevalence it is strange that for many scientists the whole notion of it is a completely alien concept until they first encounter the publication process during their postgraduate studies.

During the first year of my PhD I remember being aghast at the notion that two, or possibly three, strangers would be wholly responsible for deciding whether or not my research was deemed ‘suitable’ for publication, and despite my otherwise excellent undergraduate education I had nothing to prepare me for the whole ordeal. Thankfully I had a very experienced supervisor who was able to guide me through the whole process and teach me a few tricks of the trade (always respond politely, compliment the reviewer for their suggestions, avoid the urge to break down into tears and instead break the comments down into manageable chunks), but even now I still feel a sense of dread when an email notification appears in my inbox telling me that “the reviewer’s comments have been posted.”

By nature I am quite a defensive person, and have been known to take criticism (fair or otherwise) rather to heart, but my experiences of the peer review system have certainly helped me take a more level–headed and professional approach to the critique of my work. Crucially it has also helped me to become a better reviewer myself.

Constructive criticism is essential in order to help one develop as a researcher, and indeed as an individual, but some of the peer reviews that I have seen (and sadly been subjected to) are nothing more than mean-spirited attempts by the reviewer to assert their own supposed authority on a subject. This kind of analysis is beneficial to absolutely no one, and it should be the responsibility of the editors and administrative staff of the journals and e-zines to help eradicate it. There is always something positive to be said about any piece of research (unless it is utterly nonsensical, in which case again the editor should have stopped it from ever being submitted to a reviewer), and being totally negative in your comments will only serve as fuel for a vicious cycle in which young researchers believe that the purpose of peer review is to find fault in the work of others. Instead, good peer review should be a helpful critique of a fellow colleagues work, which politely points out any shortcomings, makes suggestions for improvements, and praises what is good.

I will now be teaching my own university students about the peer-review system, and will be asking them to mark one another’s work throughout the unit that I teach on Science Communication at Manchester Metropolitan University. I think that most undergraduate courses would benefit from a similar approach, not only to prepare future scientists, but also to help students learn how to respond to criticism and how to critique the work of others in a productive and conducive manner. By educating and encouraging young scientists in this way we can hope to potentially avoid these kinds of reactions in the future.

Teaching about peer review at university can help to eliminate bad practice (Photo credit: Gideon Burton).

For those of you who are currently reviewing a paper, I set you the challenge of explicitly writing at least one compliment to the author. This could be in regards to the excellence or originality of their research, the structure or fluidity of the article, or indeed the clarity with which they express their ideas. To those of you who are not reviewing a paper, try and find at least one positive thing to say (the colour really brings out your eyes, it’s certainly an affordable mode of transport, these scones are delicious!) the next time that your opinion is required; I guarantee that it will leave everyone feeling just a little bit more capable of themselves and what they can achieve.

By Sam Illingworth, Lecturer, Manchester Metropolitan University