“He loved mountains, or he had loved the thought of them marching on the edge of stories brought from far away; but now he was borne down by the insupportable weight of Middle-earth.”

J.R.R. Tolkien (1955) Return of the King

‘The Lord of the Rings‘ by J.R.R. Tolkien is one of the most famous english-language fantasy book series’ ever written. It set the blueprint for what European fantasy fictional settings would look like for decades and is still a cultural touchstone for storytellers in a variety of formats to this day. One of the reasons for its enduring legacy is the detail and depth of its worldbuilding – several of the languages work and can be used functionally and there is a rich and textured cultural narrative of the different peoples who inhabit the world – even though that narrative is often drenched in the culture of Tolkien’s own time, with a specific moral geography and with several races/species being depicted in a racist way. With this month marking 50 years since the death of the author and with all of this cultural and social detail, it’s interesting to take a look at the geology, and see if it holds up to the same high standard.

Geology in the Lord of the Rings books

From the vaulted and mineral-veined halls of Moria to the soft hills of the Shire, Tolkien’s descriptive style of storytelling provides us with a fairly significant amount of geological information in the Lord of the Rings books. For years people have been able to draw parallels between the descriptions in the text and locations in the real world.

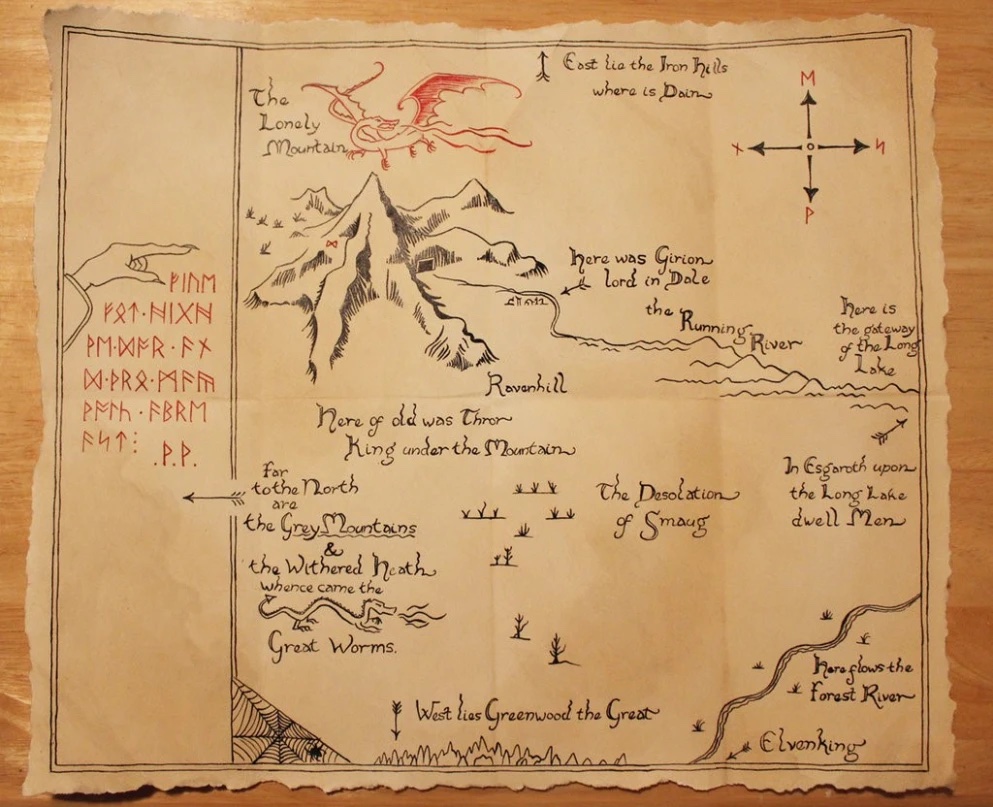

The Lonely Mountain, for instance is shown in a map from ‘The Hobbit‘ text as being a literal lonely mountain – solitary on a flat plain. It is most likely igneous “grey and silent cliffs” (The Hobbit, 1937, pg 215) and is full of mineral and gemstone deposits. This is geologically realistic, the Lonely Mountain could be a hotspot volcano, that has created a solitary stratocone. Alternatively it could be a pegmatite inselberg – a formation created by erosion. This is less likely though, as inselbergs tend to be more rounded by the erosive processes that create them, as you can see from the most famous example, the sedimentary Uluru in Australia.

A cohesive geological picture?

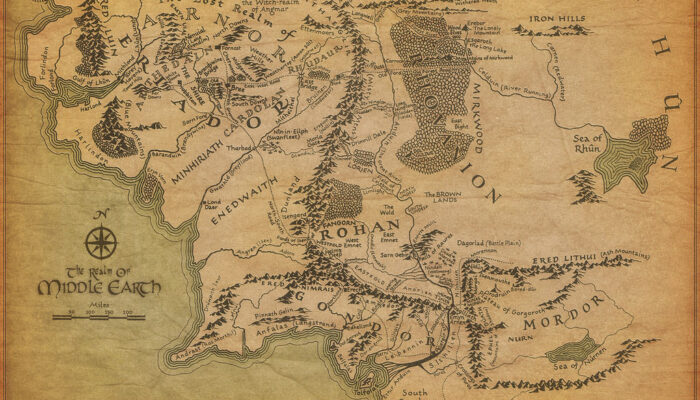

The problem comes when we try and put all the separate geological descriptions together, especially with the map that is provided in the front of the books. Several geoscientists and other scholars have tried over the years, with one of the most recent covered by one of our former bloggers, Jon Tennant, in 2014. In this 1996 paper by William Sarjeant, the author takes an enthusiastic jaunt through the possible tectonic history and development of the region where the Lord of the Rings books are set, and seeks to consolidate the text and maps provided with modern theories of plate tectonics, which were not known when Tolkien was writing these books. This attempt, although a brilliant read and definitely worth the time for any fan of fantasy geography, does still represent the way that some very large leaps have to be made to connect the individual geological and geomorphological features of the text – particularly in the entire form and placement of the Anduin River.

Interestingly although the cohesive geological picture is sometimes a struggle, as Danièle Barberis notes in her highly interesting 2007 paper on the legal and cultural mining environment depicted in Middle-earth, the cultural aspects of geology as an industry and economic source are well developed by Tolkien, particularly amongst dwarves.

It’s time to talk about the mountains…

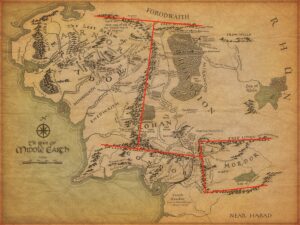

An image from Alex Acks’ blog about the problem with the mountains of Middle-earth (image credit: Alex Acks).

Now it is time to come to one of the biggest problems any geoscientist (or person familiar with.. maps) will spot the moment they look at the maps of Middle-earth. Yes. It’s time to talk about the mountains. Several of the mountain ranges and individual mountains on the map make absolutely no sense. The worst offender, of course, is Mordor, but we will get to that shortly.

Several of the mountain ranges have a very strange placement when we try to explain them with comparable real world examples – and this is most clear in the stretch of country between Rohan, Gondor and Mordor. Where the Misty Mountains meet the White Mountains a strange angular connection can be found – that is almost a right angle. These kinds of extreme angles are possible in the real world as Alex Acks explains in his 2017 post, but you have to work really hard to find them.

When ‘magic’ is a geological process

Mordor, as a section of the map, is by far the most geologically nonsensical part. No natural process can create a topography in the way that it is described in the books, a square plain fenced by mountains at right angles to each other – it’s practically impossible. So how does it exist in Lord of the Rings?! Well, luckily, Tolkien had an explanation for that – magic. Hardy souls who have traced the mentions of the formation of the continents of Middle-earth through the Silmarillion and other extended writings of Tolkien, give examples of parts of the story to explain the bizarre shape of Mordor: that Morgoth (the original big bad) chose to reshape the face of Middle-earth himself, making ‘magic’ a geological process that needs to be incorporated into the world. As a geoscientist I think you can look at this one of two ways: a frustrating way of ignoring science in the name of ‘story’, that doesn’t happen for the languages (Tolkien’s first love); or an example in fiction of a way that people have attempted to understand the shape of our world since we first started telling each other stories about it.

The role of mythology and storytelling in geoscience

The Lord of the Rings is clearly and obviously a work of fiction, a book that is strongly coded with aspects of the evils of industrialisation and war. There is perhaps an interesting lens of climate change that can be applied to the work, but first and forever it is a fantasy story. In the real world myths and legends helped people to understand the world around them for generations, and for many geoscientists, even today, exploring myths and stories provided useful information in places where the only data collected may have been in the form of oral tradition. The EGU Tectonics and Structural Geology Division blog has a wonderful series on these geological myths by Filippo Carboni and the EGU Outreach Committee recently funded a public engagement project that would work with indigenous people to incorporate traditional ways of understanding water protections with scientific ways.

So although examining the geology of the fictional world of Middle-earth is a fun game, the tales we tell each other about the real world can be enlightening as well as entertaining, and we should never stop looking for the mountains marching at the edges of our stories.

JP

Very interesting read. I love examining fictional worlds through the lens of science. I would quibble over one claim, though:

“The Lord of the Rings is clearly and obviously a work of fiction, an allegory for the evils of industrialisation and war. ”

Whereas Tolkien says,

“I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence…I think that many confuse ’applicability’ with ‘allegory’; but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author. “