In this edition of GeoEd, Sam Illingworth, a lecturer in science communication at Manchester Metropolitan University, explores the benefits of a more informal teaching style and how the incorporation of play into everyday teaching can help to engage and enthuse students who oterhwise struggle to connect with the sciences. Despite the hard work, there are some real perks to being a scientists: field work, conferences, travelling, collaborations, etc… to name but a few. The key is to show school aged children the fun side of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths) realted subjects too!

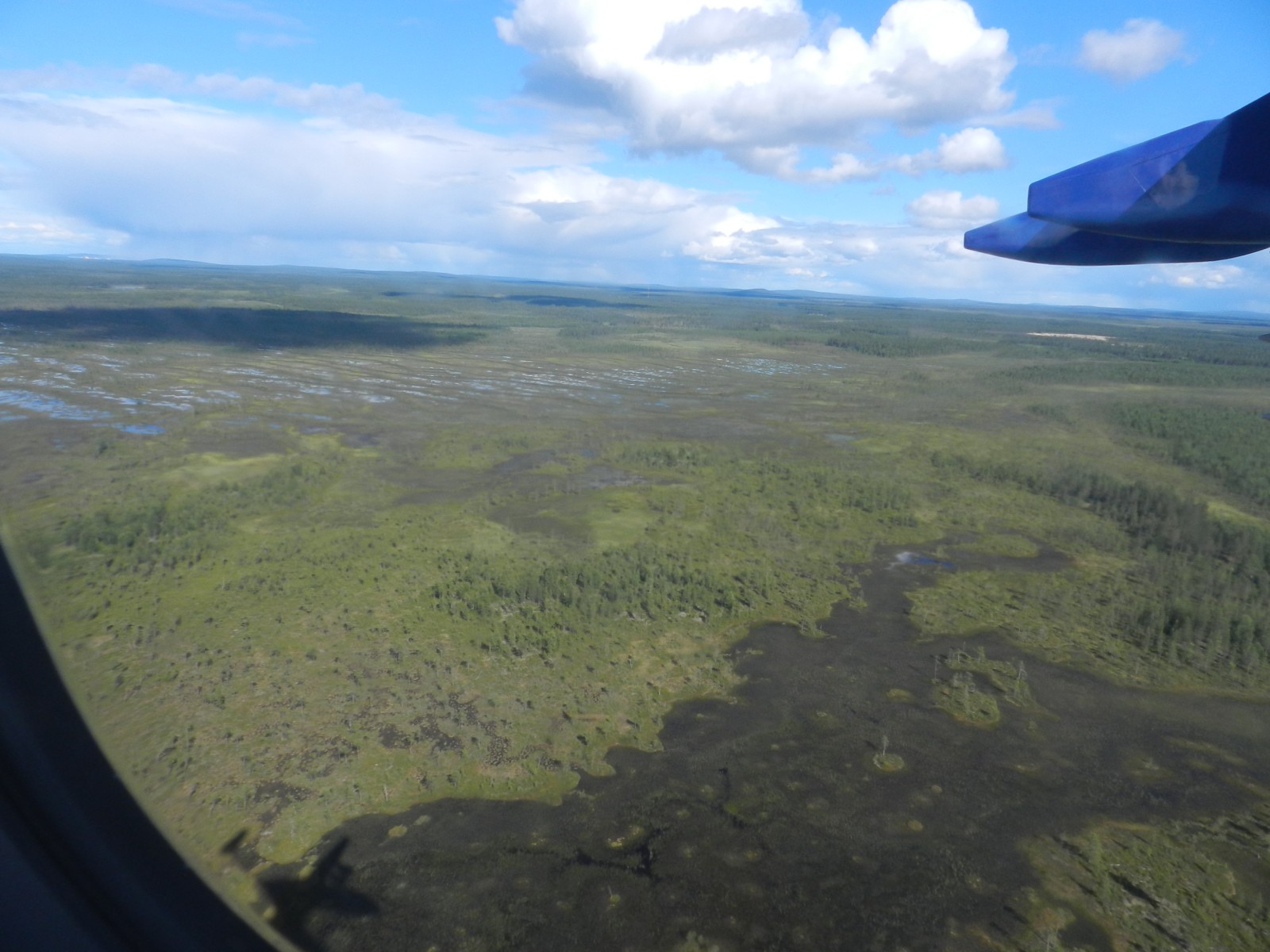

Flying 50 m above the Arctic Ocean at over 300 km per hour or flying a drone around a school playing field. These are fun activities; fun activities that are related to my research and that have genuine scientific significance. Yes, my scientific career has also involved countless hours sat reading technical documents and debugging code, but ultimately science is an extremely engaging and exciting career. If that element of fun is something that we are failing to communicate to children studying science at school, then it is no wonder that so many of them are turning away from science before they have had the chance to do something truly spectacular.

The classroom is not the only place where learning can occur (Wassermann, 1992), and it is important for students studying science to be able to explore for themselves some of the intrigue, wonder and even bemusement that science can present. In other words, it can be beneficial for the students to be given the opportunity to peel back the curtain and look at science outside the constructs of the taught curriculum. One way that this can be done is through serious play.

Serious play is so called so as to distinguish it from the negative connotations that might otherwise be associated with play. In essence serious play can be thought of as improvising with the unanticipated in ways that create new value (Schrage, 2013, pp. 2). In the context of the sciences, this may be a series of open-ended experiments that encourage students to try out their own ideas and hypotheses, without any end goal or risk of failure.

Despite the use of the term ‘serious’, this type of play is still sometimes frowned upon, as it can be seen to simplify the educational approach, by failing to acknowledge the complexities of teaching and learning (as eloquently pointed out in this excellent article). However, done correctly, play has an important role in the learning and discovery cycle. Play has ultimately been shown to be beneficial in terms of cognitive, language and social development (see e.g. Mann, 1996). Aside from these benefits it is also important to remember that play can help to communicate an often under promoted element of scientific endeavour: fun.

By Sam Illingworth, Science Communication Lecturer, Manchester Metropolitan University

References

Mann, D. 1996. Serious play. The Teachers College Record, 97, 446-469.

Schrage, M. 2013. Serious play: How the world’s best companies simulate to innovate, Harvard Business Press.

Wassermann, S. 1992. Serious play in the classroom: How messing around can win you the Nobel Prize. Childhood Education, 68, 133-139.

Pingback: Four steps to great hands-on outreach experiences – Mirjam S. Glessmer

Pingback: GeoLog | GeoEd: For the best hands-on outreach experiences, just provide opportunities for playing!