There’s a lot of emphasis on outreach to older students, i.e. those who are contemplating further education and may well wish to pursue a career in science, but shouldn’t we also target our efforts at the younger generation? Sam Illingworth highlights the importance of outreach to primary school kids – and of catching them at an age when they’re most likely to be inspired…

From my experiences working in schools across the UK, there has been a rather biased drive to deliver educational outreach to students that are either coming to the end of their compulsory education, or who are about to decide what to study at university.

However, to me this appears to be a somewhat backward approach. Yes, it is important to target students with stimulating outreach activities that inspire them to study a geosciences-related degree at university, but many of these students will already have had to make some selections regarding the speciality of their education, even at this early age.

In the UK, at the age of 16, students are asked to choose (usually) between 3 and 5 subjects to study for a further two years, a decision that will have major implications for their university education. In reality, for many students the choice of pursuing a broad scientific education occurred even earlier, with many UK students given the option at 14 of replacing some of their science lessons with those from other subjects.

Because of this early selective branching, it can often be very difficult to change the mindset of a teenager that has already taken the decision to less actively pursue the sciences in their studies. Whilst this model is not in place across the whole of Europe, it is certainly true that there is more of a focus on depth rather than breadth as a student’s education progresses. Furthermore, research suggests that for many pupils the dissatisfaction with science sets in at the end of their primary school (10-11) years.

The brain is far more impressionable in earlier life than in maturity, and with increasing age, the ability to learn and to be influenced declines. Peak impressionability is between the ages of zero and three, and it begins to taper off significantly after the age of eight. Therefore, in order to encourage as many students as possible to actively pursue a broad scientific education it is important to instil a fascination and desire to do science at an early age.

Targeting students between the ages of 5 and 11 requires a slightly different approach to working with teenagers, but many of the core principals remain the same, with the students needing to be both educated and engaged.

In educating the students, it is very important not to work with a deficit model, an idea that focuses on the students’ lack of knowledge, rather than a student-centeredness approach based around the understanding of the learner and the learning process. In my opinion the use of a deficit approach to outreach is akin to the feeling you get when a car mechanic sighs at your understanding of spark plugs; it is not a very positive experience to be told that you do not know something!

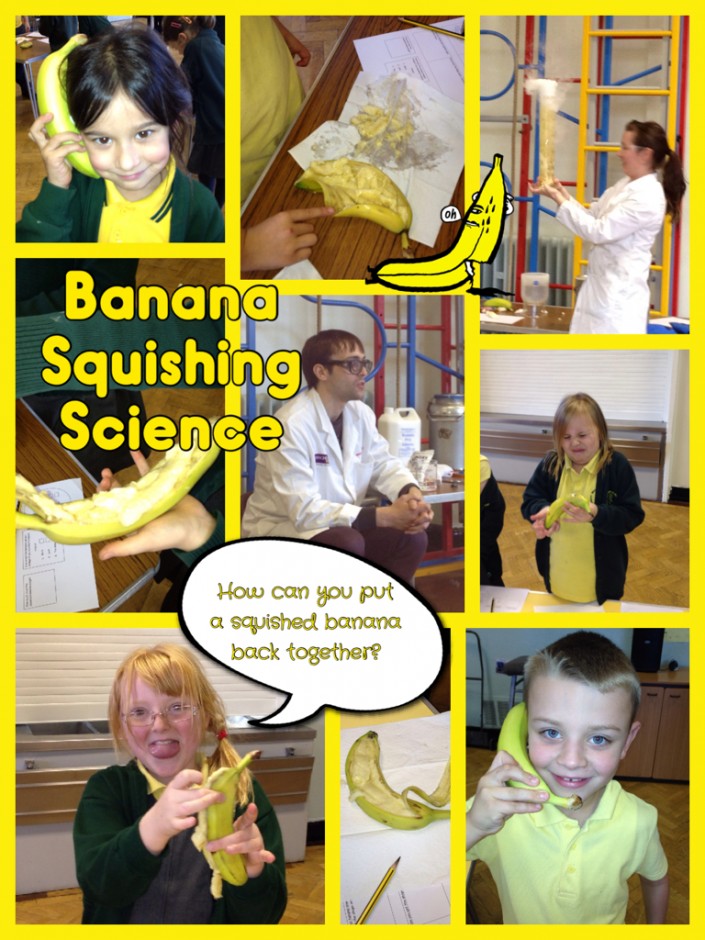

Instead, if we use an approach that focuses on what the students have already learnt in class and on concepts and items that they understand and are familiar with, then this can reinforce the work we are doing, and will leave the students feeling empowered and therefore far more willing to contribute. For example, in a recent activity that I ran for a group of seven-year old pupils I wanted to teach them about how to conduct a scientific experiment. Knowing that the notion of a fair test was a part of the curriculum I developed an activity that saw the students squashing bananas, weighing them before and after, and recording their results in a scientific manner. The students were then able to build on their knowledge base of what constituted a fair test to learn about the scientific process, using equipment (bananas and weighing scales) that they were familiar with.

Outreach activities that build on a previous knowledge base can be far more engaging than those built around a deficit model. (Credit: Louise Bousfield)

In order to engage with younger students it is advisable to make the outreach activity as practical and interactive as possible. A recent report from the UK’s Wellcome Trust found (not surprisingly) that young people enjoy practical activities in which they can actively get involved rather than just watch. That being said, from personal experience there is still room for traditional assembly-style presentations, providing that the students are kept involved and that there are lots of opportunities for questions!

I recently gave a school assembly to around 150 students, between the ages of five and eleven on the subject of ‘Who is a Scientist?’ The assembly lasted for about an hour, including twenty-five minutes of open-ended questions, and could have gone on for much longer; in fact, I only had to stop taking questions so that the students were able to leave school on time!

School assemblies are a great opportunity to engage with a large number of students. (Credit: Sam Illingworth)

Working with younger children can be a liberating and exhilarating experience. They are yet to develop the cynicism and awkwardness that can sometimes make engaging with older children so energy zapping. They can also surprise you in the most wonderful ways; in the assembly that I mentioned above one softly spoken student asked me ‘Why, if human[s] evolved from monkeys are there still monkeys?’

Carefully developed outreach activities can educate and engage younger students, thereby instilling a love of science at this early and impressionable age. Such activities can have a large influence on the degree to which they decide to sustain their scientific educations, which will ultimately have a profound effect on them far beyond the confines of the classroom.

By Sam Illingworth, Lecturer, Manchester Metropolitan University

References:

Clemence, M., N. Gilby, J. Shah, J. Swiecicka, and D. Warren: Wellcome Trust Monitor: wave 2 tracking public views on science, biomedical research and science education report, Wellcome Trust, 2014

Osborne, J., & Dillon, J.: Science education in Europe: Critical reflections. London: The Nuffield Foundation, 2008

UNICEF: The Importance of Early Childhood Development, 12 October 2008. Accessed 5 June 2014.

Ziman, J.: Public understanding of science, Science, Technology & Human Values, 16(1), 99-105, 1991

Pingback: Wordpress Blogs - Wordpress Blogs .NET