Jane Qiu shares her experience of shadowing atmospheric scientists some 5000 metres above sea level after being awarded the EGU’s science journalism fellowship. To find out how she got there, see her last post, A sky-high view on pollution in the Himalayas: the journey.

Lab with a view

After six days of strenuous hike, the Pyramid was finally in sight. At the foot of the majestic Khumbu Glacier, the main building, completed in 1990, consists of a three-storey stone building with a pyramid-shaped, solar-panel roof. It’s home to a data-processing centre, several laboratories and warehouses, as well as a lodge — with bedrooms, showers (yes, there is hot water), kitchen and a large common room — that can host 20 people at a time.

At dinner time, a gourmet Italian meal — prosciutto, mozzarella salad, penne arrabiata, and a bottle of Merlot — was presented to us by the skillful Nepalese chef. Having had dhaba (a popular Nepalese dish) for almost every meal for the last few days, this was extremely enticing. But the altitude effect was gaining momentum, and my stomach ejected everything that had gone in.

It transpired that my blood oxygen level hovered just above 60% (the value is normally between 96%-99% for healthy individuals). And Gian Pietro Verza, the station manager and an experienced mountaineer, decided that I ought to lie down and inhale oxygen for a couple of hours — with a Pyramid staff sitting next to me and measuring my oxygen levels every 10 minutes.

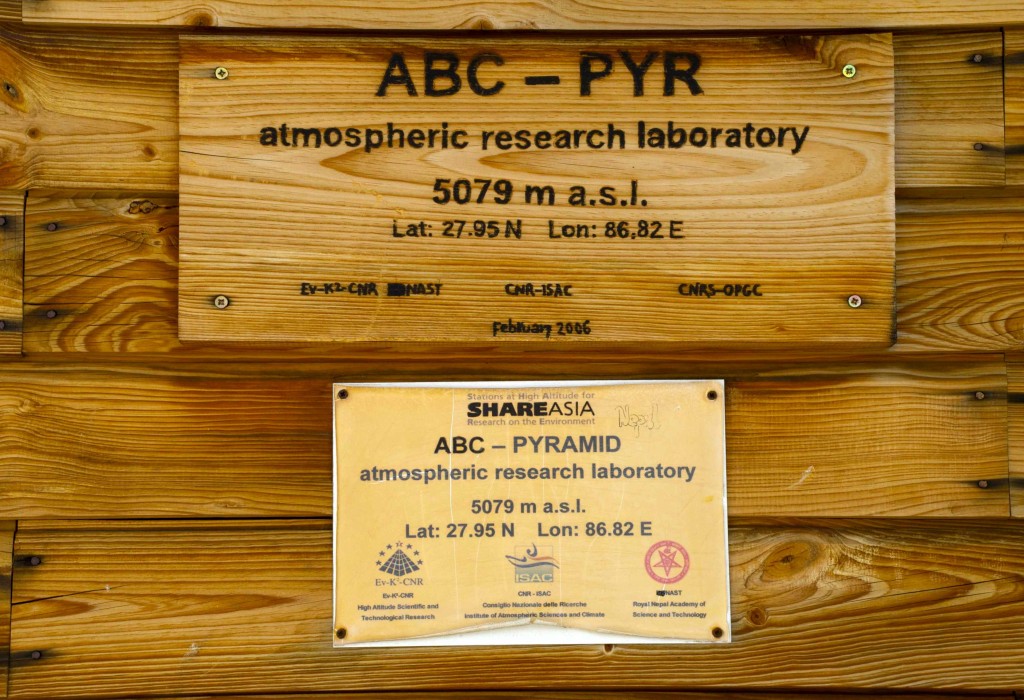

The observatory, which was set up by the Ev-K2-CNR Committee and the Nepal Academy of Science and Technology, has allowed continuous measurements of pollutants since 2006. (Credit: Jane Qiu)

I was much better the next morning, but every single movement was a big ordeal. Having put on all the layers of clothing and tying the boot laces, I felt I could do with a little lying down. But the calling of the glorious Himalayan Sun was irresistible. So I went with the researchers to the observatory on top of an adjacent hill. It consists of a small hut and a whole suit of instruments, perching next to rows of solar panels near the terminus of the magnificent Khumbu Glacier.

In addition to meteorology and solar radiation, the instruments measure various properties of aerosols, such as size, concentration, total mass and optical properties (whether they absorb or reflect light). They also assess the level of mercury as well as a number of gases, including carbon dioxide, water vapour and ozone. A few devices on the roof pass air samples through filters to be analyzed in the laboratory for their chemical composition.

The coolest gadget is an automated apparatus called a sun photometer. It has its ‘head’ down most of the time, but ‘wakes up’ every 15 minutes to point at the Sun. The embedded optical system and filtering devices allow it to measure how transparent the atmospheric column is. Scientists use this information to deduce the quantity of aerosols and gases present.

All the measurements are transmitted to the data-processing centre in the main building. The satellite connection allows remote control of the instruments and real-time data access — from any part of the world. The Italian team comes every spring and autumn to calibrate instruments and install new sensors. For the rest of the year, the Nepalese staff, including Kaji Bista, Pema Sherpa and Laxman Adhikari, have a crucial role in keeping things running.

In addition to the Pyramid, there are another 8 weather stations along the Khumbu Valley — from 2660 metres above sea level near Lukla to 8,000 metres at the South Col (the ridge between Everest and Lhotse, the fourth highest mountain in the world). This has provided a rare glimpse of atmospheric circulation and pollutant transport in the Himalayas.

Peak station

The Nepalese staff, such as Pema Sherpa (right) and Lakpa Sonam, have a crucial role in keeping the equipment functional all year round. (Credit: Jane Qiu)

A few days later, I set off to see an automated weather station on Kala Patthar (meaning black rock in Nepali). It’s a big dark bump at 5,600 metres above sea level on the south ridge of the Pumori (7161 metres), which is referred to by climbers as “Everest’s daughter”.

We stopped for lunch at the village Gorakshep — the last outpost before the Everest Base Camp — and heard the sad news that somebody had died from altitude sickness on Kala Patthar the day before. I learned a few days later that it was a German gentleman in his sixties who we happened to have met and shared a lodge with at the village Tengboche on our way up.

From Gorakshep, it’s a two-hour hike — with a lot of breaks as I huffed and puffed my lungs out. We crossed an ancient lake bed, navigated through a series of steep switchbacks, and had some serious scrambling before reaching the wind-swept summit ridge. The weather-station towers stood atop the boulders, among the prayer flags fluttering in the wind. A myriad of weather parameters, such as temperature, humidity, pressure, wind speed and direction, are transmitted to the Pyramid in real time.

With a magnificent view of the Everest (8,848 metres) and the Lhotse (8,516 metres), which are connected to each other via the South Col, the site also boasts the highest webcam in the world — the Mount Everest Webcam. It was installed by Italian and Nepalese researchers as part of an Ev-K2-CNR-supported project to understand climate change in the Himalayas.

Looking over to the South Col, I tried to imagine what it would be like to install a weather station there at an altitude of 8,000 metres — certainly the highest in the world. In 2008, an expedition team consisting of three Italian climbers and five Nepalese sherpas, including Pema Sherpa, went up to the ridge with all the heavy scientific equipment.

Pemba Wangchu traversing a ladder in the Khumbu Icefall, while Pema Sherpa had crossed safely. They were part of an expedition team to install a weather station at the South Col at 8,000 metres above sea level. (Credit: SHARE Everest Expedition)

The team drilled deep into the ground to fix the masts, so they would be stable in harsh conditions for as long as possible. The electronic instruments also have to sustain extreme conditions, such as frigid temperatures, strong winds, low pressure, and ice formation.

Their efforts have paid off. One striking finding is the records of above-zero temperatures at the South Col. This coincided with massive ice falls, presumably because the warm temperatures caused snowmelt and triggered avalanches. This is particularly interesting in light of the recent surprising findings that Tibetan glaciers are losing ice at altitudes as high as 6,000 metres.

Himalayan cleanup

All these pursuits are, of course, not purely academic. Pollution in the Himalayas could have far-flung impact. Once reaching the high mountains, pollutants — especially dust, black carbon, and organic compounds — could increase glacier melt, pollute streams, poison ecosystems, and even change monsoon patterns, threatening the livelihood of millions of people.

With the aerosol observatory at the Pyramid and the 9 weather stations along the Khumbu Valley, the researchers now have the data to pinpoint pollution sources and transport mechanisms and determine how pollutants might react with each other along the way to form new chemicals. This, together with a new modelling initiative, will be able to inform emission-reduction policies in the Himalayas.

Further reading

Qiu, J. Pollutants capture the high ground in the Himalayas. Science, 339, 1030-1031 (2013).

By Jane Qiu, Science Writer

Karma David

What a wonderful blog. The steel ladder bridge of Khumbu Icefall is extremely unbelievable.

Nepal Kailash Trekking Pvt. Ltd.

It’s great!