To kick off the New Year, we have invited a guest author, Takafumi Maruishi, a researcher in the Research Division for Volcanic Disasters / Center for Volcano Research Promotion, National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience, Japan. He explains the scaling law of lava dome growth and its physical insight.

Effusive eruptions—when magma reaches the surface and is extruded as lava—are one of the main ways volcanoes build and reshape their landscapes. When the magma is silica-rich, its high viscosity can keep it close to the vent, so lava accumulates and grows into dome-shaped bodies known as lava domes. Remarkably, these domes can add substantial relief within only a few months, letting us watch volcanic landscapes take shape almost in real time.

Once lava is emplaced, it spreads under gravity while cooling and gradually turning into solid rock. But what sets the growth mechanism and final shape of a dome, as deformation and cooling proceed together? In recent decades, volcanologists have tracked this evolution in detail through careful field mapping and time-series measurements during dome-building eruptions. In this post, I use the 1979 Soufrière dome eruption as a case study and sketch a simple framework in which surface cooling provides a key mechanical control on dome growth.

By Takafumi Maruishi (National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience)

The 1979 Soufrière eruption: A natural experiment

Soufrière Volcano on St. Vincent in the Lesser Antilles is a ~1200 m high stratovolcano with a history of both explosive and effusive activity. In April 1979, an explosive phase produced a large ash cloud and prompted the evacuation of ~17,000 people. From May onward, activity shifted to sustained lava extrusion that continued for roughly five months (Huppert et al., 1982).

A key feature that makes this eruption particularly valuable for mechanical analysis is its setting: the dome grew on a comparatively flat crater floor. The preceding explosive phase had smoothed the floor with fragmented deposits, creating an ideal natural laboratory for examining first-order controls on dome growth without the complications of complex topography.

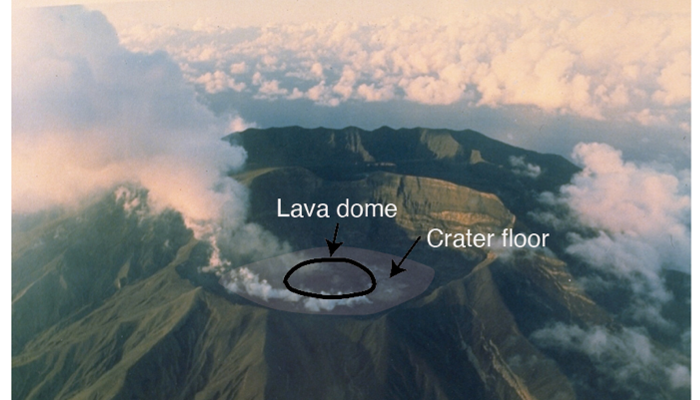

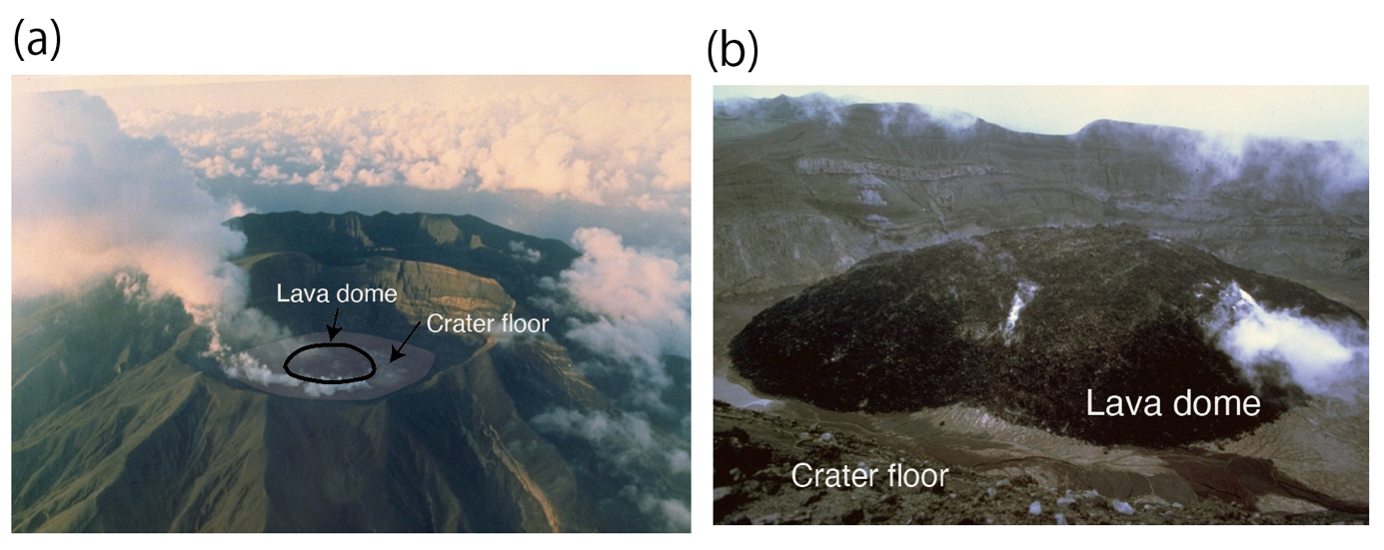

Fig. 1. Photographs of the Soufrière lava dome. (a) Newly extruded dome photographed from the southwest on 15 May 1979. (b) Post-eruption view in 1983, showing the dome with a diameter exceeding 840 m and thickness of about 130 m. From the Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program: GVP-05128 and GVP-05064.

Evolution of dome shape: what the time series shows

Continuous field observations documented the time evolution of dome shape during the five-month extrusion. Successive lava-front positions mapped across the crater floor show that the lava progressively expanded to occupy most of the floor (see a plan-view evolution of lava fronts in Fig. 9 of Huppert et al. (1982)). Meanwhile, thickness measurements indicate that the dome ultimately reached about 130 m.

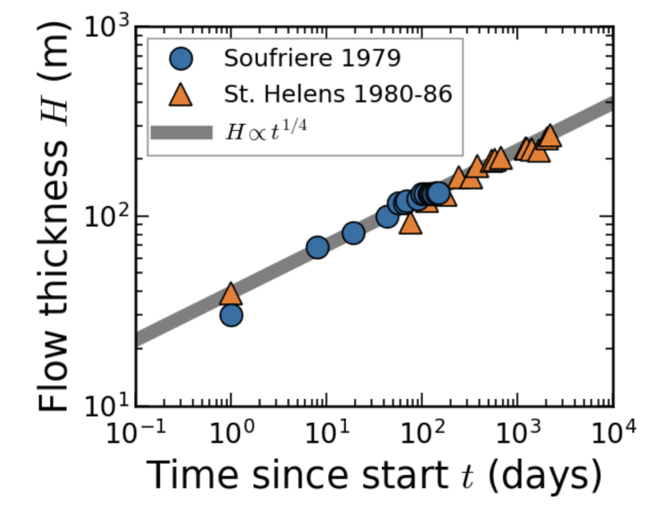

Here is where things get interesting. The thickness increases through time following a pattern well approximated by a fourth-root-of-time trend (H ∝ t1/4). Data from the Mount St. Helens dome (1980–86) show remarkably similar behaviour (Swanson & Holcomb, 1990).

This growth pattern contrasts sharply with the simplest baseline theory for viscous gravity currents spreading on a rigid horizontal surface under constant supply. In that classical picture, the current advances while maintaining an approximately constant characteristic thickness (Huppert, 1982). The Soufrière dome instead thickens systematically, suggesting that an additional, time-evolving mechanical element becomes important.

Fig. 2. Temporal evolution of dome thickness for Soufrière 1979 and Mount St. Helens 1980–86, with a t1/4 reference trend. Data are taken from Huppert et al. (1982) and Swanson and Holcomb (1990), respectively.

Insights from field exposures: The two-layer architecture

Field exposures provide a direct window into the internal structure that develops during dome construction. At Soufrière, crater-wall exposures reveal cross-sections through a prehistoric dome, showing two contrasting domains (see a cross-section of its outcrop in Fig.14 of Huppert et al. (1982)).

The interior is relatively coherent and dominated by columnar-jointed andesite, with columns oriented approximately perpendicular to the ground surface. Because columnar joints form normal to cooling surfaces, this geometry indicates that, after emplacement, the core behaved as a largely continuous body that cooled gradually in place under a sustained thermal gradient.

In contrast, the exterior consists of a thick zone of blocky lava fragments. This blocky carapace indicates repeated brittle failure, fragmentation, and reworking at the dome margin, consistent with an outer shell that periodically broke up as the dome advanced and deformed.

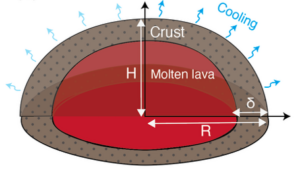

Based on these observations, we can conceptualize a flowing lava dome as a hot, deformable interior that feeds extrusion and accommodates deformation, surrounded by a cooling-generated crust that fractures and moves as blocks.

Fig. 3. Conceptual architecture showing a hot molten interior surrounded by a fractured outer crust.

A thermo-mechanical scaling argument

Can we link this two-layer structure to the observed fourth-root thickening trend? Here is a simple physical argument.

Let R denote dome radius, H dome thickness, and δ crust thickness. The exterior crust forms as the lava surface cools to the atmosphere, with heat conducted away from the interior. For conduction-dominated cooling, the crust thickness follows thermal diffusion and therefore increases with the square root of time: δ ∝ t1/2.

Next, consider the radial force balance. The dome’s own weight drives lateral spreading: the characteristic radial surface slope scales as H/R, and the relevant body force acts over a dome volume that scales as R2H. Multiplying these gives a gravitational driving force that scales as (H/R) × (R2H), or simply RH2. Resistance is provided by the exterior crust in contact with the ground; if the resisting force scales with the basal contact area of the crust, that area scales as Rδ.

Balancing driving and resisting forces, and combining with the thermal scaling for crust growth, we obtain H ∝ t1/4. This provides a consistent interpretation of the field observations: as the crust thickens with time, resistance increases, and the flow must thicken to maintain spreading.

This scaling picture is supported by analogue experiments that explicitly incorporate surface cooling. Such experiments reproduce dome-like morphologies and growth behaviour similar to natural domes, confirming that a cooled carapace can regulate spreading (Griffiths and Fink, 1993; Fink and Griffiths, 1998).

References

Fink, J. H., & Griffiths, R. W. (1998). Morphology, eruption rates, and rheology of lava domes: Insights from laboratory models. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 103(B1), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1029/97JB02838

Griffiths, R. W., & Fink, J. H. (1993). Effects of surface cooling on the spreading of lava flows and domes. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 252, 667–702. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112093003933

Huppert, H. E. (1982). The propagation of two-dimensional and axisymmetric viscous gravity currents over a rigid horizontal surface. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 121, 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112082001797

Huppert, H. E., Shepherd, J. B., Sigurdsson, R. H., & Sparks, R. S. J. (1982). On lava dome growth, with application to the 1979 lava extrusion of the Soufrière of St. Vincent. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 14(3–4), 199–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(82)90062-2

Swanson, D. A., & Holcomb, R. T. (1990). Regularities in growth of the Mount St. Helens dacite dome, 1980–1986. In Lava Flows and Domes: Emplacement Mechanisms and Hazard Implications (pp. 3-24). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-74379-5_1

Edited by Yuto Sasaki