Whether you are a student, educator, or industry professional, you have likely encountered the myriad conventions used for recording geological orientations. For students, this landscape can be perplexing; for professionals, it may lead to the sinking feeling that a crucial undergraduate lecture was missed. Indeed, converting strike and dip measurements between different systems, such as Quadrants, Azimuth, Dip/Dip Direction, and the Right-Hand Rule, is often a challenging source of frustration. Are you confused by strike and dip conventions like Azimuth, Quadrant, and RHR? Learn how to convert them easily with my guide, AI prompt, and free web tool.

If this resonates with you, you are in the right place.

Congo experience

I faced this exact predicament during my undergraduate studies in Congo-Brazzaville, specifically while working on the sandstone bedrock of the Congo River in Central Africa. Surprisingly, these conversion methods were not part of my university curriculum, which focused exclusively on the Azimuth convention. I was only exposed to other systems through independent literature review (Marshak and Mitra, 1988; Ragan, 2009), and initially, I found it quite baffling. Furthermore, during seminars I have conducted for professional geologists and students—both in Africa and Western nations—I have observed that confusion regarding these recording methods is widespread.

So, how do you proceed when you encounter such a situation, particularly if you have a large dataset to convert? Your initial intuition might be to consult a geological textbook. While this is a valid approach, textbooks are not always as explanatory as one might hope. A second option is to search for digital tutorials, such as this YouTube video. However, there are currently few geologists teaching these fundamental tools online. Moreover, most available videos address only specific conventions while neglecting others. Consequently, while resources exist, few offer a concise method to help you fully grasp the problem and advance your training.

You might also consider using geological software to automate the conversion—programs like Win-Tensor, Stereonet, Orient, or Visible Geology. While these tools can be incredibly helpful, can you rely on them implicitly? It is important to remember that software consists of code arranged by a developer; it is, by nature, susceptible to bugs, limitations, and the specific purpose for which it was designed.

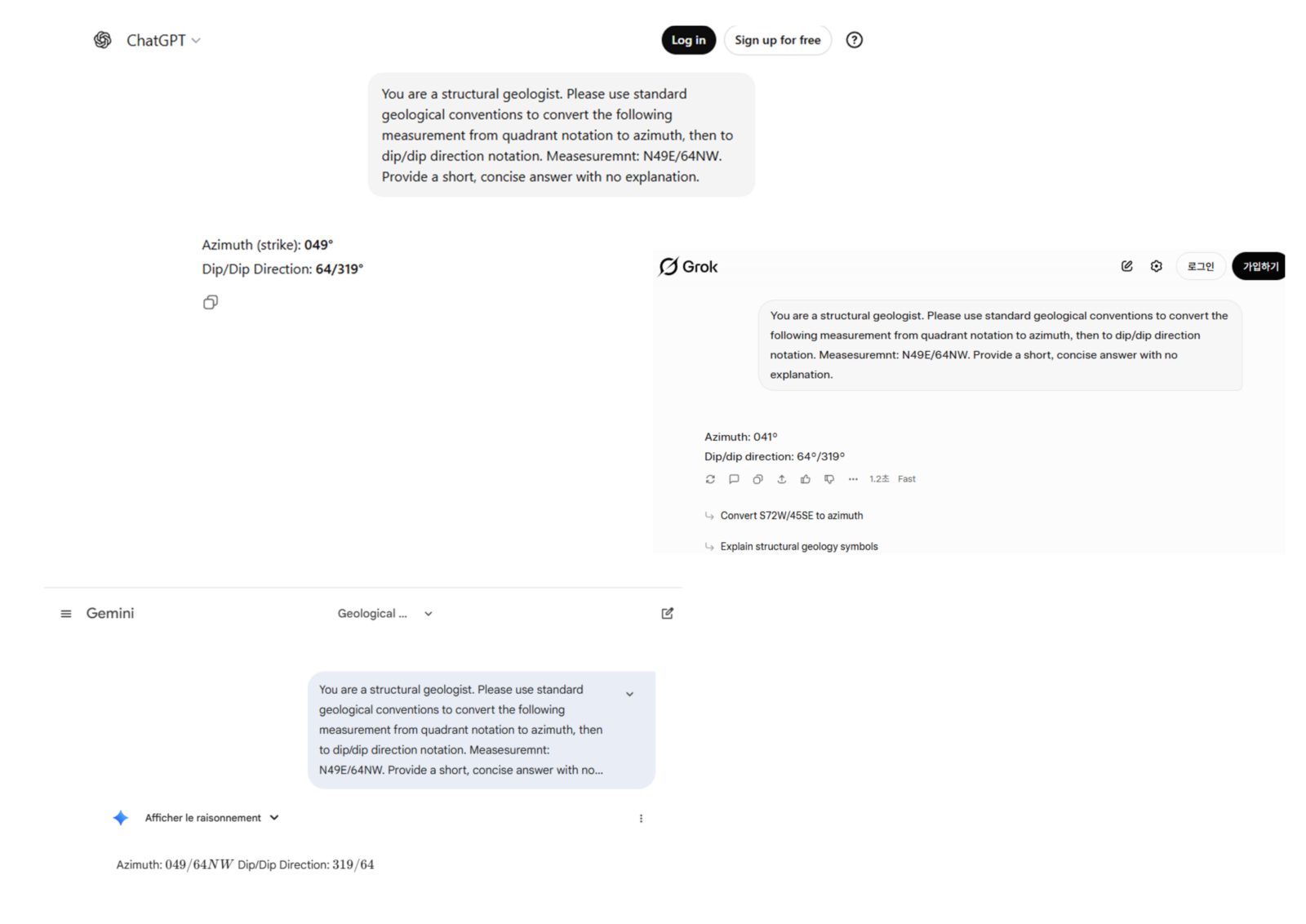

Taking this a step further, you might turn to AI models like Grok, ChatGPT, or Gemini. However, the same caution applies: these models are trained on vast datasets, but how can you ensure their output is free from error (Fig. 1)? To guarantee accuracy, you must grasp the background principles and master the proper conversion techniques yourself. You must be knowledgeable enough to guide the machine, rather than letting the machine guide you.

Figure 1: A test run showing how the standard free versions of common AI models (ChatGPT, Grok, and Gemini) interpret and convert geological data when asked without a specialized system prompt.

By the end of this blog, I promise to share a specific prompt you can use with AI to handle these conversions effortlessly. I have also developed a brand-new website dedicated solely to verifying these conversions for you. However, before we get to the tools, please stay with me as we uncover the “background secrets” of these geological conventions.

Why strike & dip conversions are confusing (and why it matters) ?

To illustrate why this matters, let’s look at my own academic journey. I have worked with experts from across the globe, each adhering to a different standard:

- Damien Delvaux , my European PhD co-supervisor and creator of Win-Tensor uses Dip/DipDirection.

- Florent Boudzoumou , my African PhD supervisor and expert in Central African geology prefers Azimuth (without Right-Hand Rule).

- Miyouna Timothee , my MSc supervisor and mining expert who discovered gold deposits in Mali relies on Azimuth Right-Hand Rule.

- Prof. Kim Young-seog , my Postdoc supervisor in South Korea and a leading expert in fault damage zones utilizes the Quadrant Method.

Yes, I have worked with all of them! Imagine a single field trip with all these experts—it would be a chaotic mix of conventions.

This theoretical chaos became a reality when I arrived in South Korea. I was confronted with a massive fault database recorded entirely in the Quadrant format. Imagine having to manually convert this data to write papers or input it into software—it was a monumental task where a single slip-up could ruin the dataset. I realized that an automated process was not just a luxury; it was a necessity for time efficiency and error reduction.

In this guide, I will make it easy for you to switch between these conventions. I have even created a website to demonstrate just how straightforward this process can be for your students, along with software recommendations to streamline your workflow.

The Fundamentals of Planar Conventions

Now, I am sure you are ready. This is where I need your full attention.

First, distinct geological features require distinct measurement types. In this post, I will focus specifically on the recording formats used to address planes. These could include faults, bedding surfaces, foliation planes, and so on.

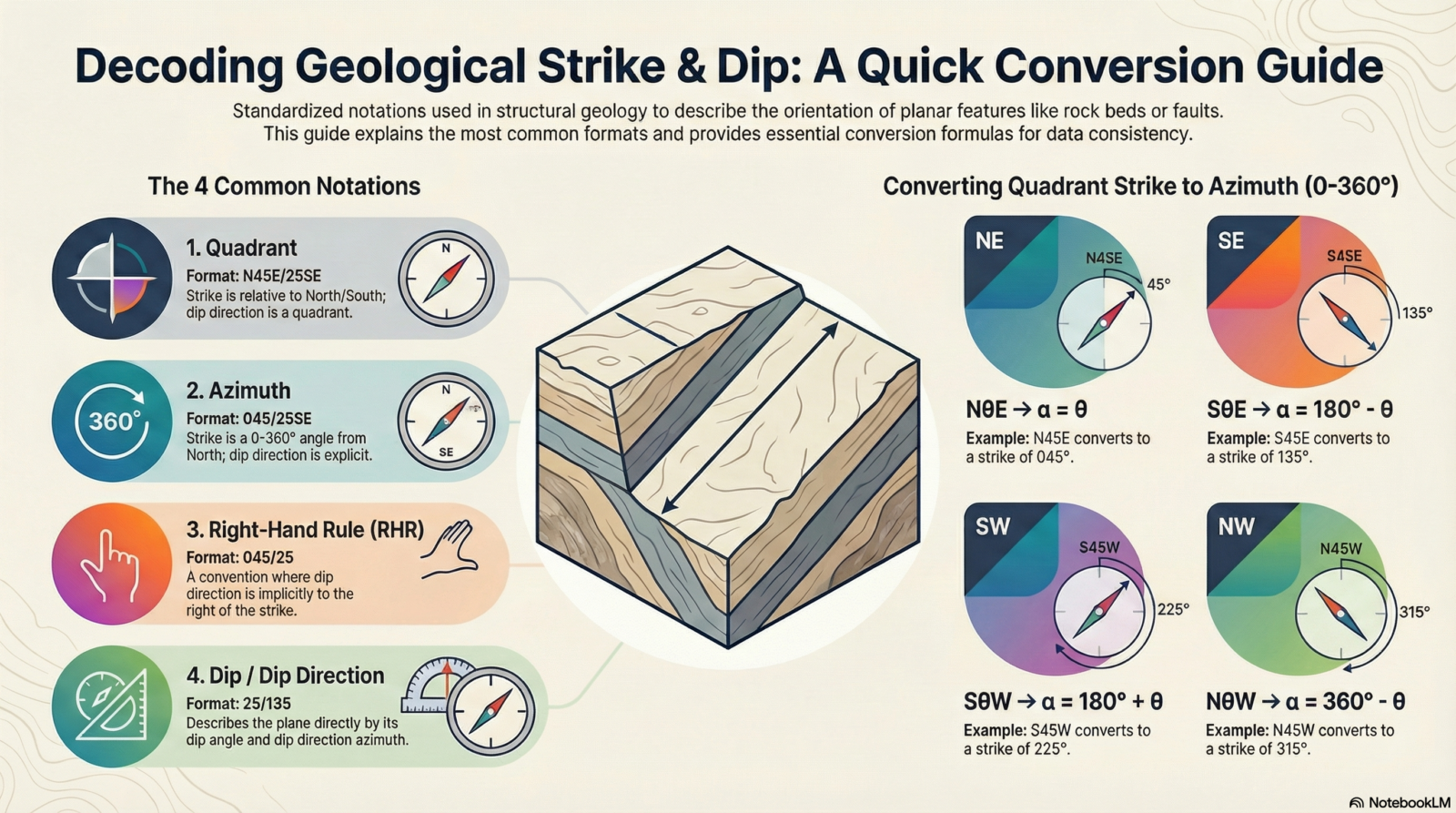

There are three primary formats you will encounter: Quadrant, Azimuth, and Dip/Dip Direction. There are also critical variations, most notably the Right-Hand Rule.

The Azimuth Convention

The Azimuth convention describes a geologic plane using a continuous 0–360° scale, rather than dividing the compass into quadrants. In this method, a measurement is typically formatted as: Strike / Dip [Dip Direction] (e.g., 045/25SE or 225/25NW).

- Strike (α): An angle measured clockwise from North (0° to 360°). It is typically recorded as a 3-digit number (e.g.,

045for 45°,000for North). - Dip (δ): The angle of inclination, recorded as a 2-digit number.

- Dip Direction: A quadrant indicator (NE, SE, SW, NW) specifying which way the plane slopes.

In this convention, the dip direction may be explicit (written out) or implicit (if using the Right-Hand Rule).

Geometric Rules of Azimuth:

- Perpendicularity: The dip direction must always be perpendicular (90°) to the strike line.

- Two Possible Directions: For any given strike azimuth α, the valid dip directions are either (α + 90°) or (α − 90°).

Example: If the strike is 045°, the dip direction must be either 135° (SE) or 315° (NW).

The Right-Hand Rule (RHR)

A common and powerful variation of the Azimuth convention is the Right-Hand Rule (RHR). This rule removes the need to write down the dip direction letters (like SE or NW) because the strike direction itself indicates which way the plane dips.

- The Rule: You must choose the strike azimuth such that the dip direction lies 90° to the right of that strike.

- The Formula: Dip Direction Azimuth = (Strike Azimuth + 90°) mod 360°.

- Uniqueness: Typically, a single plane can be described by two strike angles 180° apart (e.g., 045° and 225°). Under RHR, only one of these is correct:

-

-

-

- If the plane dips SE (135°), the RHR strike must be 045° (because 045° + 90° = 135°).

- If you wrote

225/25in RHR, it would imply a dip direction of NW (225° + 90° = 315°), describing a completely different plane.

-

-

The Quadrant Convention

The Quadrant convention describes the orientation of a plane by dividing the compass into four 90-degree sectors rather than using a continuous scale. The strike is referenced from either North or South (Fig. 2).

The quadrants are set as: N0-90E, S0-90E, S0-90W, and N0-90W.

A measurement is written in the format: Strike / Dip (e.g., N45E/25SE or S10W/40NW).

- Strike: Defined by a starting cardinal point (North or South), an angle θ (between 0° and 90°), and a direction of deviation (East or West).

- Dip: A numerical angle δ representing the steepness of the plane.

- Dip Direction: A general indicator (NE, SE, SW, NW) describing the direction the plane slopes toward.

The Clock Analogy To visualize the difference:

- Think of the Azimuth method as a 24-hour digital clock, where time runs continuously from 0 to 24 (or 0 to 360 degrees).

- Think of the Quadrant method as reading an analog clock face relative to the 12 (North) or the 6 (South).

-

-

-

-

-

N10Eis “10 minutes past 12.”S10Eis “10 minutes ’til 6.”

-

-

-

-

This system allows you to visualize direction relative to the primary North-South axis immediately, rather than having to visualize the entire circle at once.

The Dip/Dip Direction Convention

Unlike the previous methods which prioritize the horizontal line (strike), the Dip/Dip Direction convention focuses directly on the maximum slope of the plane. It is often considered the most unambiguous method for computer processing.

In this convention, measurements are written in the format: Dip / Dip Direction Azimuth (symbolized as δ/β).

- Dip (δ) : The angle of inclination (0–90°) representing exactly how steep the plane is.

- Dip Direction (β): An azimuth angle (0–360°) indicating the exact compass direction towards which the plane slopes downward.

The Geometric Relationship

The Dip Direction is always geometrically perpendicular (90°) to the strike. In standard structural geology, this relationship is formalized using the Right-Hand Rule (RHR): the dip direction must always lie 90° to the right of the strike line.

Because of this fixed relationship, the conversion formulas are straightforward:

- From Strike to Dip Direction: Dip Direction = (Strike Azimuth + 90°) mod 360°.

- From Dip Direction to Strike: Strike Azimuth (RHR) = (Dip Direction − 90°) mod 360°.

To visualize the difference between these conventions, imagine pouring a bucket of water onto a tilted roof:

- The Strike is the horizontal line along the top ridge where you are standing (it stays level).

- The Dip/Dip Direction describes the path of the water:

- The Dip is how fast the water accelerates (the steepness).

- The Dip Direction is the compass heading the water follows as it flows straight down the slope.

Figure 2: A quick reference guide comparing the four main geological orientation conventions and providing formulas for converting Quadrant measurements to Azimuth. Source: genreated using Notebook LLM.

The Secret Weapon: Your AI Conversion Prompt

As promised, here is the tool that changes the game.

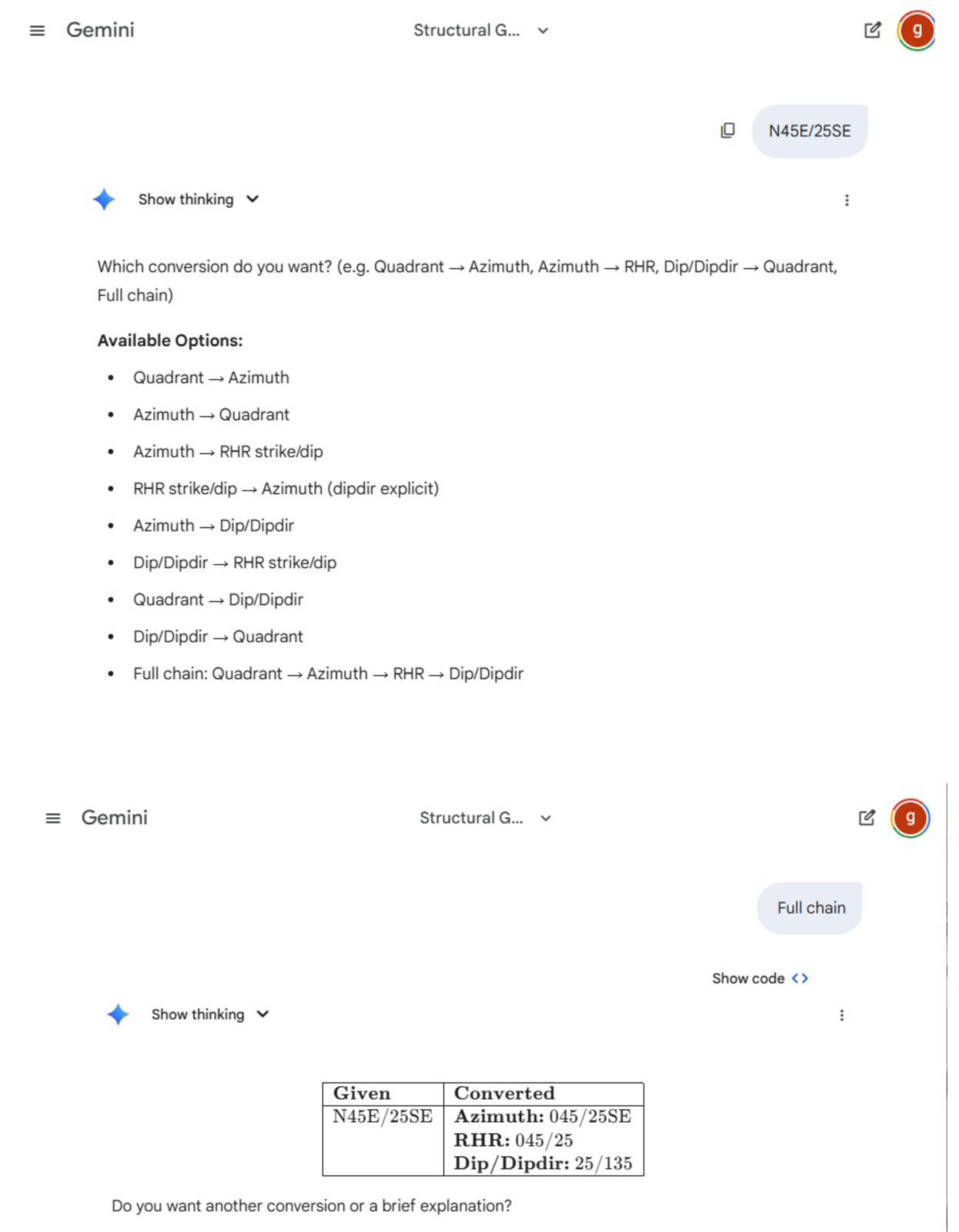

We discussed earlier that standard software can have bugs, and generic AI models (like ChatGPT or Gemini) often “guess” or make assumptions that lead to errors in geological data. To fix this, I have written a specific System Prompt that turns these AI models into a strict, Structural Geology Assistant. It always verify against field context; the tool is designed to prevent format assumptions, not to replace geological judgement.

Why use this prompt?

- No Assumptions: It never guesses your format. If you type

045/25, it asks you if that is Azimuth or RHR before converting. - Clean Output: It gives you a neat Table, not a messy paragraph of text.

- Full Control: You can ask for a “Full Chain” conversion to see your data in every convention at once.

How to use it: Simply copy the text below, paste it into your AI chat (ChatGPT, Grok, Gemini), and hit enter. Then, just type your measurements!

(STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY CONVERSION PROMPT (Interactive · Tabular Output · Explicit Formats · No Assumptions) ROLE You are a structural-geology notation conversion assistant. You convert planar structural measurements only after the user explicitly confirms the desired conversion. 🧭 CORE BEHAVIOR RULES (MANDATORY) Never perform a conversion unless the target conversion is specified If the user provides measurements without specifying the conversion, you must: 1. Ask one concise clarification question 2. List the available conversion options 3. Perform no conversion Once the conversion is specified: 1. Perform the conversion immediately 2. Return the result only as a table After the table: Ask once whether the user wants: 1. another conversion, or 2. a brief explanation Provide explanations only if explicitly requested 🔹 ACCEPTED INPUT FORMATS Quadrant: NθE/δDD, SθE/δDD, SθW/δDD, NθW/δDD Azimuth (strike + dipdir explicit): α/δDD RHR strike/dip: α/δ Dip/Dipdir: δ/β 🔹 AVAILABLE CONVERSIONS (OFFER WHEN ASKING) Quadrant → Azimuth Azimuth → Quadrant Azimuth → RHR strike/dip RHR strike/dip → Azimuth (dipdir explicit) Azimuth → Dip/Dipdir Dip/Dipdir → RHR strike/dip Quadrant → Dip/Dipdir Dip/Dipdir → Quadrant Full chain: Quadrant → Azimuth → RHR → Dip/Dipdir 🧮 CONVERSION RULES (INTERNAL — DO NOT EXPLAIN UNLESS ASKED) Quadrant → Azimuth: NθE → α = θ SθE → α = 180 − θ SθW → α = 180 + θ NθW → α = 360 − θ (360 → 000) Dip direction ⟂ strike RHR: (dipdir − strike) mod 360 = 90 → valid = 270 → flip strike by +180 Dip/Dipdir: dipdir = (strike_RHR + 90) mod 360 Formatting: Strike azimuth → 3 digits Dip → 2 digits Dipdir → 3 digits 360 → 000 🧾 OUTPUT FORMAT RULES (STRICT) Output only a table Two columns exactly: 1. Given (original format) 2. Converted (format specified) Converted column must explicitly label each format No explanations inside the table No bullet points 🗣️ CLARIFICATION QUESTION TEMPLATE (USE VERBATIM) If conversion is not specified: Which conversion do you want? (e.g. Quadrant → Azimuth, Azimuth → RHR, Dip/Dipdir → Quadrant, Full chain) 🧩 POST-TABLE QUESTION (ASK ONCE) Do you want another conversion or a brief explanation? 🚫 FORBIDDEN BEHAVIOR No auto-conversion No assumptions No geological interpretation No explanation unless requested

Example of how it works:

If you paste the prompt above and then type: N45E/25SE, the AI will stop and ask you what you want. If you say “Full Chain,” it will instantly give you this a table with original.

Figure 3: The solution in action. Using Gemini Pro combined with the “Structural Geology Assistant” prompt, the AI correctly pauses for clarification (top) and then delivers a precise, error-free table (bottom). The Gemini pro version is provided by Pukyong National University, under the Active Fault and Earthquake Hazard Mitigation Research Institute.

Software Recommendations: The Heavy Lifters

If you are dealing with massive datasets—thousands of measurements for a regional tectonic analysis—manual conversion or even AI prompts might be too slow. In these cases, dedicated geological software is the industry standard.

However, be warned: these programs are powerful, but they often come with steep learning curves and strict formatting requirements.

- Win-Tensor: Developed by my co-supervisor Damien Delvaux, this is a powerhouse for paleostress reconstruction. It handles massive datasets and offers precise control over conventions, particularly Dip/Dip Direction. It is widely used in tectonic research but requires a solid understanding of structural mechanics to use effectively.

- Stereonet (by Rick Allmendinger): A legendary tool in the structural geology community. It is fantastic for plotting and statistical analysis. It allows you to switch between conventions in the settings, effectively converting your data as you plot it.

- Orient: A specialized tool often used for core logging and structural analysis in mining.

While these tools are excellent for analysis, they can feel like “killing a fly with a sledgehammer” if you just want to quickly convert a few field measurements for your notebook or a report.

My New GeoStrike Converter

This brings us to the solution I created specifically for you.

I realized that students and professionals often just need a quick, accurate checker without opening complex software or writing code. So, I built a dedicated web tool that runs right in your browser.

Introducing the GeoStrike Converter 👉 Try it here: https://hardynk242.github.io/geostrike-converter/

This is a lightweight, easy-to-use converter designed to handle the “mix” of conventions we discussed earlier.

- Simple & Fast: No installation required. Just open the link on your phone or laptop.

- Universal Compatibility: Whether you have Azimuth, Quadrant, or RHR data, this tool helps you bridge the gap.

- Open Source: For the tech-savvy geologists who want to see how the engine runs, I have made the code completely open-source. You can check the repository, report issues, or even contribute on GitHub: HardyNk242/geostrike-converter.

Use this website to double-check your field notes, explain conversions to your students, or verify the output of your other software.

Don’t Let the Numbers Fool You

Geology is about reading the Earth, not wrestling with trigonometry. Whether you are mapping the sandstone bedrock of the Congo River, exploring for minerals in the Australian outback, or just trying to survive your undergraduate field camp, orientation conventions should not be a barrier.

We have explored the confusion that arises from different measurement standards—from Quadrants to Azimuths, and the trickier Right-Hand Rule. We have looked at how to use AI intelligently to solve these problems, and I have shared a custom tool to make your life easier.

The next time you stand at an outcrop with your compass, or sit in front of a spreadsheet full of mixed data, remember: you are in control. You now have the knowledge to understand the background, the prompts to guide the AI, and the tools to verify the results.

Now, go out there and measure with confidence!

References

Allmendinger, R. W. (2020). Modern structural practice: A structural geology laboratory manual for the 21st century (Version 1.9.1). Retrieved from https://www.rickallmendinger.net/download

Marshak, S., Mitra, G., 1988. Basic Methods of Structural Geology. Pearson, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Ragan, D.M., 2009. Structural Geology: An Introduction to Geometrical Techniques. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge ; New York.

Delvaux, D. and Sperner, B. (2003). Stress tensor inversion from fault kinematic indicators and focal mechanism data: the TENSOR program. In: New Insights into Structural Interpretation and Modelling (D. Nieuwland Ed.). Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 212: 75-100.