The Aboriginals Australians had and hopefully will continue to have an important oral tradition, especially related to impacts, tsunamis, earthquakes and volcanoes. This time, I would like to set our new narrative in southeast Australia, where the Booandik people tell a story suggesting how their ancestors witnessed and interpreted volcanic activity in the Mount Gambier area. The story, reported by the Scottish missionary Mrs. James Smith (Fig. 1) in her book

pertains to the so-called “Dreamtime”, which represent somehow the oral tradition of the Aboriginals Australians. However, the concept of “Dreamtime” is much more complex and really fascinating, so I leave it for now to avoid oversimplifications.

Fig. 1. Jenny Westendorf (left) and James Smith (right) at Mt. Gambier in 1880. State Library of South Australia – B 16562, Public domain.

The long journey of Craitbul and his family

Craitbul was the great giant, ancestor of the Aboriginal Australians, who inhabited the Mount Muirhead with his family, a wife and two sons. Craitbul and his wife were so immense that they had to bend their heads passing below the highest gum trees. They lived a happy life for a long time, gathering roots to be cooked in their oven, which was the top of Mount Muirhead. One night, while the family was resting, a bird called Bullin roused them from their dreams: an evil spirit named Tennateona was coming to bring death.

The family moved in search of a safer place, heading towards Mount Schank, where they thought the spirit Tennateona could not reach them. They built their “wurli” (hut) and set up a new oven on top of Mount Schank, starting to enjoy themselves. But again, one night they heard the shriek of the bird Bullin and they were forced to abandon their new campsite to escape the evil spirit in great fear.

This time, the family headed inland, away from the water, where the spirits reside, reaching Mount Gambier where they again set up their oven and cooked their gathered roots. Finally, they lived in peace for a long time, away from the evil spirit Tennateona. But one day, water inundated the oven extinguishing the fire; they made an other, but water came again, and so on until they built the fourth oven and decided to finally settle inside a cave on the side of the peak (Smith, 1880: 14 – 15).

The charm of this narrative, is how apparently it accurately describes the chronological successions of the Pleistocene eruption of Mt. Muirhead, followed by the Holocene volcanic events of Mt. Schank and Mt. Gambier. In addition, the story also accurately portrays the maar (EGU Blog – GeoTalk: Explosive testing with Greg Valentine) nature of the Mt. Gambier, which would periodically fill with water (Wilkie, 2020).

Mt. Gambier Volcanic Complex

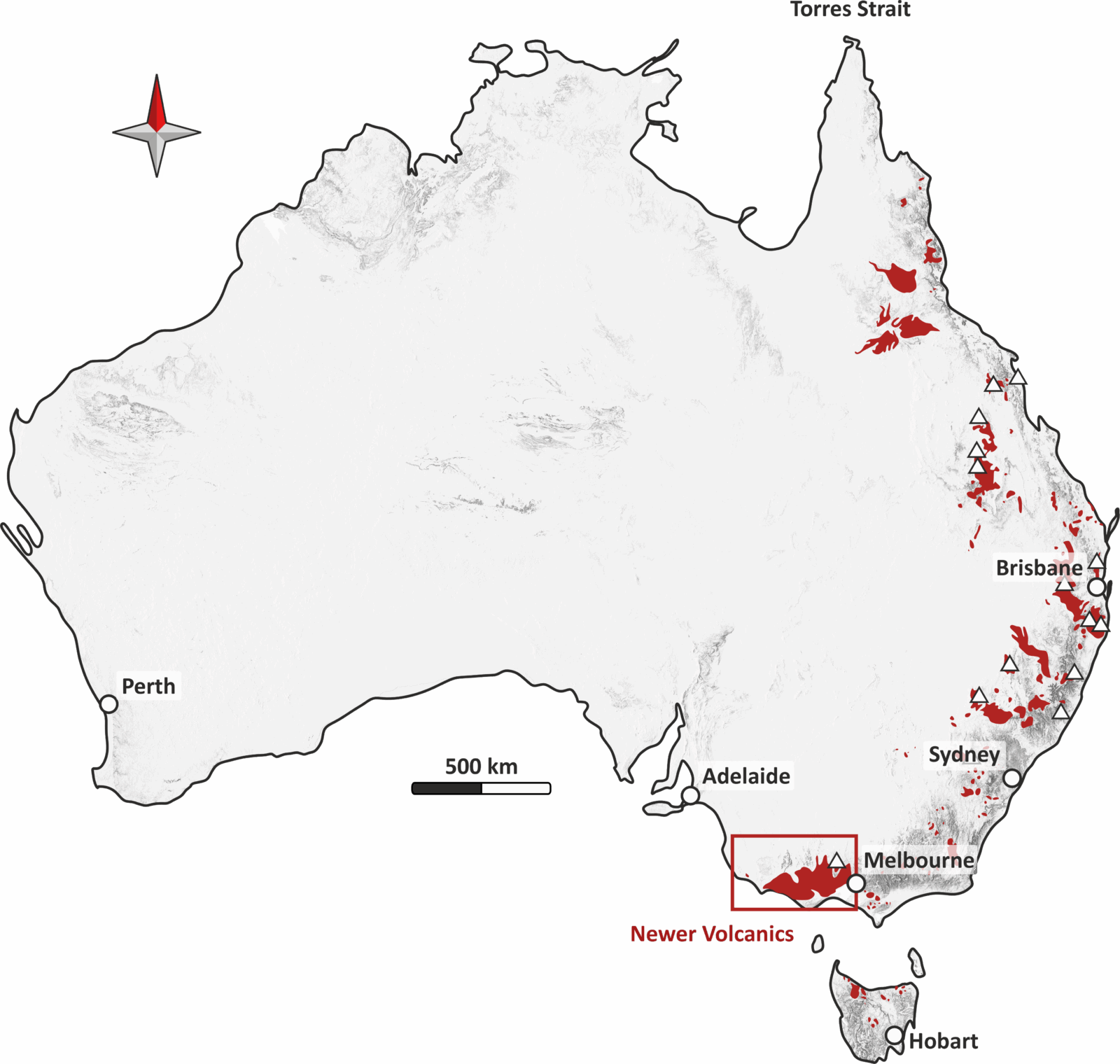

Mt. Gabier, Mt. Schank and Mt. Muirhead pertain to the Mt. Gambier Vulcanic Complex, located in SE Australia. It represents the youngest expression of the long lasting intra-plate volcanism occurring along the entire eastern Australian passive margin (Cas et al., 2016). The volcanism appears now aligned N-S, spanning for about 4400 km from Torres Strait in the north to Tasmania in the south (Fig. 2). The origins are still debated but the latest interpretations suggest how it may be linked to stress transmitted by the New Zealand active plate margin in the east. The volcanic activity is subdivided in three groups based on the age of volcanic events: Older Volcanics (95 – 19 Ma), Macedon-Trentham group (7 – 6 Ma) and Newer Volcanics (8 Ma – 5 ka). The latter extending ca. E-W in the south, to which Mt. Gambier Volcanic Complex pertains (Fig. 2), are being still classified as an active volcanic province (Cas et al., 2016).

Fig. 2. Australian topography displayed in Hillshade, with the volcanic groups in red and the main volcanic centres (white triangles). Modified after Cohen et al. (2017).

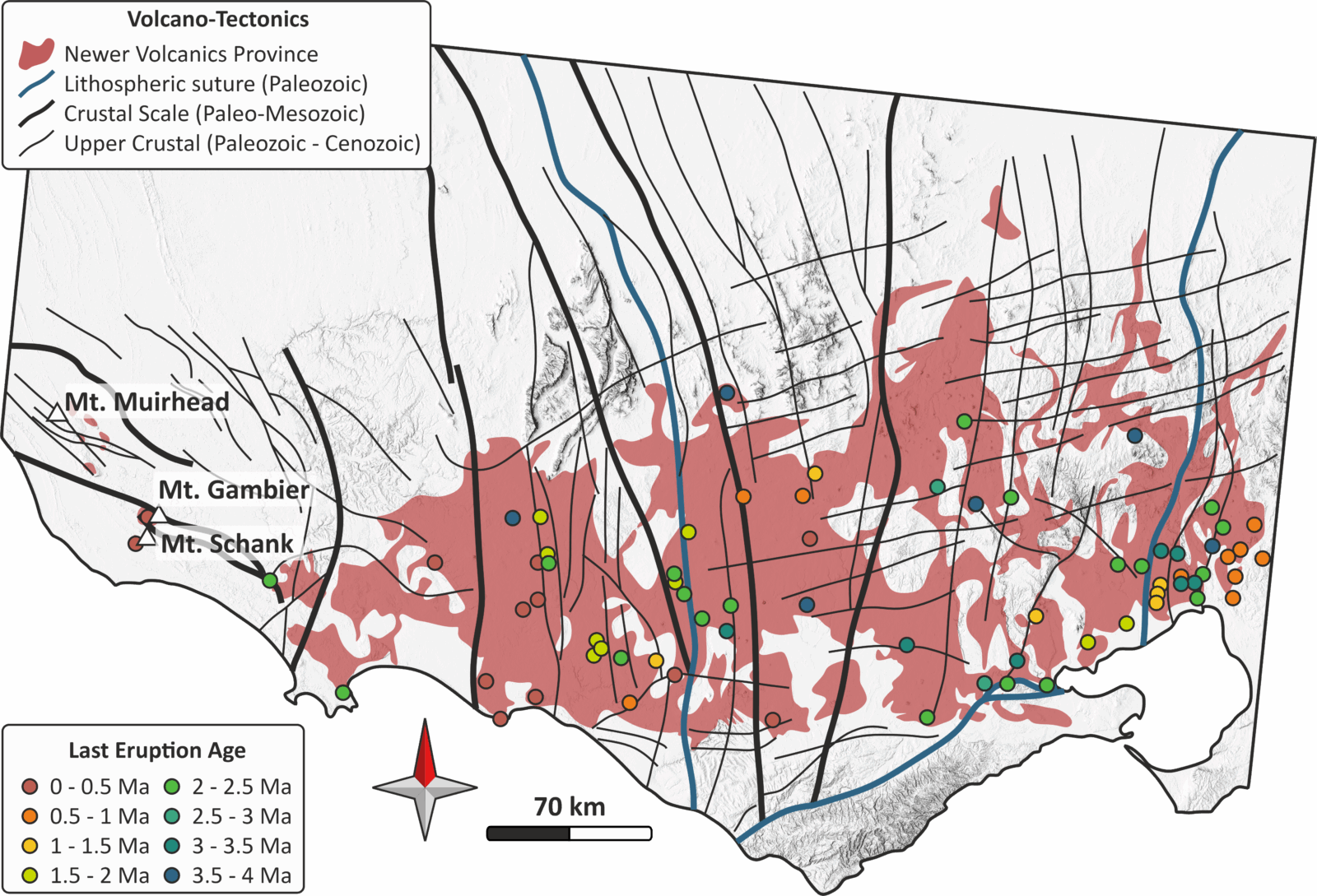

The Mt. Gambier Volcanic Complex is an isolated cluster of scoria cones and maars with minor associated lavas. It is composed of several volcanoes, among which Mt. Muirhead is located in the northwest, while Mt. Gambier and Mt. Schank are located, close to each other, in the southeast (Fig. 3). The volcanic centres of the Mt. Gambier Volcanic Complex are located in correspondence of major crustal-scale faults, i.e., the Tartwaup Fault System (Fig. 3). The deeply rooted ca. NW-SE trending faults formed during the Meso–Cenozoic rifting, while the faults mainly constrained within the upper crust formed in response to the present-day NW–SE-oriented transpressive regime (Cas et al., 2016).

Mt. Muirhead is suggested to have erupted in the Pleistocene, about 1.5 Ma, followed by a later eruptive phase, shifted south-eastwards, of Mt. Schank and Mt. Gambier volcanoes around 4 to 4.6 ka (South Australia Earth Resources, 2013; Mount Gambier Volcanic Complex State Heritage Area).

Fig. 3. Zoom in the Newer Volcanics area, showing the different fault lineaments and the last eruptions ages. Note the location of Mt. Muirhead, Mt. Gambier and Mt. Shank in the west, whose ages for their last eruption are dated in the 0 – 0.5 Ma. Modified after Cas et al. (2016).

In particular, Mt. Gambier was characterized by phreatomagmatic eruptions driven by the presence of ground water filling the crater, entering the deep magma chambers causing explosive and destructive eruptions; even today, the craters are filled with water to create the Blue and Valley lakes among others (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Birds’ eye view from the north of the Mt. Gambier lakes (Blues Lake in the southeast and Valley Lake in the northwest). Modified from Google Earth.

Behind the “Dreaming”

Such chronological order of volcanic eruptions is well reflected in the Craitbul journey legend, suggesting how Aboriginals Australians might have witness the three eruptions in order. This also means that this particular tale has lasted for thousands of years… orally ! Such long lasting time for an oral narrative is always astonishing and fascinating, especially by considering what the Aboriginals Australians “Dreaming” represents. It is not a fixed legendary/mythological past, but a dynamic living system, whose narrative evolves with the society and where the importance is given not to the timing but the occurrence itself.

A further interesting fact, is that the Aboriginals Australians most likely arrived to Australia ~60 ka via at least two distinct routes (Gandini et al., 2025), while the last dated eruption of Mt. Muirhead is dated way earlier (ca. 1.5 Ma). Such discrepancy might also mean that the Aboriginals Australians might have witness a later eruption, whose geological evidences are yet… or, just to speculate a bit with fascination, that they might have modified tales of even earlier people.

References

Cas, R.A.F., van Otterloo, J., Blaikie, T.N., van den Hove, J., 2016. The dynamics of a very large intra-plate continental basaltic volcanic province, the Newer Volcanics Province, SE Australia, and implications for other provinces. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 446, 123 – 172. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP446.8

Cohen, B.E., Mark, D.F., Fallon, S.J., Stephenson, P.J., 2017. Holocene-Neogene volcanism in northeastern Australia: Chronology and eruption history. Quaternary Geology 39, 79 – 91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2017.01.003

Gandini, F., et al., 2025. Genomic evidence supports the “long chronology” for the peopling of Sahul. Sci. Adv.11,eady9493. 10.1126/sciadv.ady9493

Mount Gambier Volcanic Complex State Heritage Area. https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/environment/docs/her-fact-mtgambiervolcanicsha-factsheet.pdf. Last visited on 01.12.2025

Smith, J., 1880. The Booandik Tribe of South Australian Aborigines: a sketch of their habits, customs, legends, and language. Government Printer, North-Terrace, Adelaide.

South Australia Earth Resources, 2013. https://demstedpprodaue12.blob.core.windows.net/mesac-public/resources/files/4022687/ISM14.pdf. Last visited on 01.12.2025

Wilkie, B., 2020. Volcanism in Aboriginal Australian oral traditions. Geology Today 36(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/gto.12324