These blogposts present interviews with outstanding scientists that bloomed and shape the theory that revolutionised Earth Sciences — Plate Tectonics. Get to know them, learn from their experience, discover the pieces of advice they share and find out where the newest challenges lie!

Meeting Xavier Le Pichon

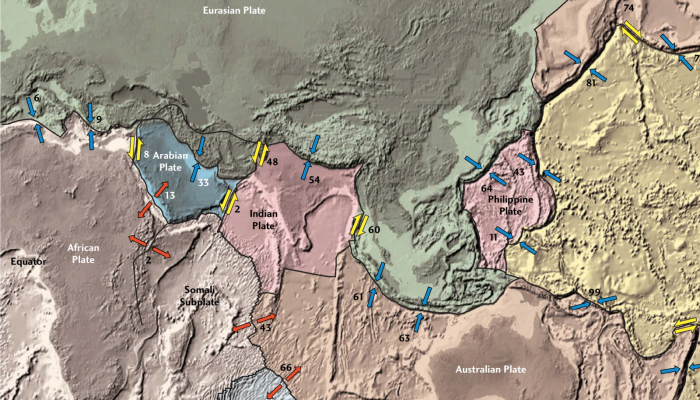

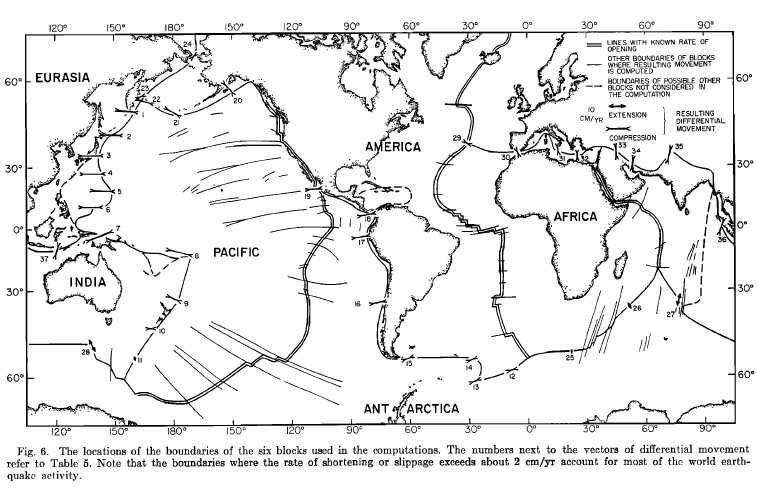

Prof. Xavier Le Pichon is one of the pioneers of the theory of plate tectonics. He developed the first global-scale predictable quantitative model of plate motion. The model, published in 1968, accounted for most of the seismicity at plate boundaries. Among many substantial contributions to the field, he also published, together with Jean Francheteau and Jean Bonnin, the first book on plate tectonics in 1973.

Your contributions have led to great advancements of our understanding of Plate Tectonics as we know it today. What‘s your main interest and what motivates your research?

My interest is the Earth and how it behaves. Discovering what type of animal the Earth is. I think of the Earth as a living organism, and we have to understand it. It’s very interesting to take the Earth as something that evolves, that changes, and that you have to understand how it evolves. The whole thing about research is getting very intimate with it and knowing really its behaviour.

I think of the Earth as a living organism

What would you say is the favourite aspect of your research?

I do not have any favourite aspect, but I think that to explain the change in the Earth is captivating. For example, how did we pass from an Earth where there were a single continent and a single ocean, ~200 Ma, to something where the continents are as dispersed as they are now… This had a tremendous influence on many things, including evolution, biology, climate… We know, for example, that when all the continents were together the pace of the evolution was much smaller than when continents are dispersed. All this fascinates me. I believe that if there is something that is not understood, you have to understand it. The basic question that proves you are a human is, you always have the “why” in your mind as the main thing that is present.

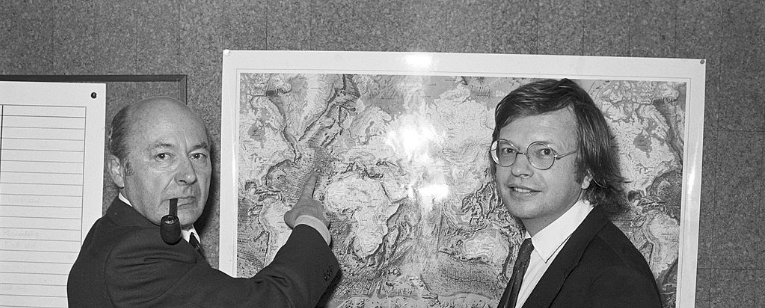

Claude Riffaud and Xavier Le Pichon – Credit: Jean-Claude Deutsch/Paris Match

What do you consider is the main problem that you solved during research?

I have been interested in many different aspects… I’m best known by the fact that I’ve been one of those who promoted plate tectonics. I made the first global model of quantifying the motion of the plates, knowing everywhere what would be the motion absorbed in the plate boundary. Also, I made the first finite and precise reconstruction of the configuration of the Earth, for nowadays, 70 Ma, 200 Ma, and so on. I also think that I was the first that proved that the Earth’s expansion did not work. Because if you take the shortening that is absorbed in the trenches of the world, in the mountain belts, and you claim there is no shortening there, then you are left only with the expansion of the ridges. And the expansion is asymmetric, and it’s produced much more in the east-west sense than it is in the north-south sense. And if you have that going on for several tens of millions of years, then the Earth would have a shape which is completely non-hydrostatic. It would not respect what the Earth has to have to be a planetary body turning on itself. So the Earth’s expansion was clearly impossible.

I believe that science that is completely regulated

top-down is not efficient

Le Pichon, X. (1968). Sea-floor spreading and continental drift. Journal of Geophysical Research, 73(12), 3661–3697.

After being many years active in the academia, looking back, what would you change to improve how science in your field is done today?

I never worried about “what is done”, I worried about “what I do”. I have always found a way to get money, to get a position and to get a lab. I changed labs quite a few times. I created a few labs… I think it is a question of adjusting. I believe that science that is completely regulated top-down is not efficient. I think there has to be a lot of freedom. At least for fundamental science. For applied science, I don’t know but I think it is probably about the same. The reason is very basic: what is the purpose of research? It’s to discover something that is totally unexpected. If it is expected, then it’s not a discovery. When the guy who does the planification says: “we will focus all our energy to find out about that”, how does he know “that” is the thing that is going to come out? The most important things in the evolution of research have been totally unexpected and came from people that had no planification whatsoever of what they should find.

The most important things in the evolution of research have been totally unexpected

Where do you see the biggest challenges in your field right now?

Le Pichon, Francheteau, Bonnin (1973). Plate Tectonics: Developments in Geotectonics, 6 – Credit: Amazon

The plate tectonic was really a revolution that changed completely the concept. And it took a few tens of years to adjust to this revolution. Actually, we are still in the phase of adjusting to that. For example, we are adjusting to the fact that to understand that plate tectonics is not only what happens at the surface, but that it implies things that happen in the interior of the Earth, in the mantle and below. This is not fully understood. And we do not understand one very important thing, which is that plate tectonics is a relatively new thing on the Earth. In the beginning, there was no plate tectonics as we know it nowadays. And I think that even the style of the plate tectonics has changed in the last was 200 Ma for example. It probably was not the same before Pangea… So we have still lots of things to understand, and to incorporate. And then, the main thing about discoveries, again, is that they are unexpected. So, I would not be surprised that major discoveries focus our energy in a completely new direction in the near future. I think we are approaching a time where it seems that we need to trigger something else to get into something new.

I am very afraid of people who get specialized too early

When you were an Early Career Researcher, what was your motivation, what stimulated you most?

Riffaud, Le Pichon (1976). Expédition ‘Famous’ à 3000 m sous l’Atlantique. Paris: Albin Michel. – Credit: Amazon

The fact that strikes me the most when I think about Europe is that the student’s mobility has been greatly increased and I think that this is extremely important. The mobility I had was not too frequent in my time – I have moved a lot: I moved to the United States, where I was offered a professorship, and came back, then I was an invited professor in other places, Oxford, Tokyo… I have created three different laboratories, and I’ve been in many places in the world. I think this is very important because you change with time and you cannot get stuck in a given thing. I think this is very basic in research. I mean, you learn a lot by comparing. You have to move, and confront yourself to other laboratories, to other ways to teach… Otherwise, you get stuck in a certain frame and that can be very dangerous. Then you become more interested in promoting your position and the place where you are than in the discoveries. Or you end up trying to be what your professor was and trying to imitate the guy that taught you is certainly one of the worst things you can do. I think anything that promotes mobility and independence and possibilities to change is a very good thing.

I am very afraid of people who get specialized too early. Of course, it is easier to get a job if you have a narrow speciality, you are more immediately usable. But I think the result is quite bad, quite often. You first have to see the different possibilities and then progressively you find out that you best express yourself in a certain direction, in a certain field. And that requests time and several tries and so on.

When you were a young researcher, did you always see yourself staying in academia?

I always wanted to do research. I wanted the freedom to choose. And I always went to places where I was sure that I would decide myself what type of research I would do. If that was not anymore the case, I quitted and I changed. I was very firm about the fact that I wanted to choose myself my own research direction. This has been a problem with financing. I had to change my source of financing. Whenever I had a problem with the state and the administration, I would go to oil people and other types of European financing in order to be able to keep this freedom.

You have to go to a place where research is thriving

The last question for today’s Early Career Scientists: what advice would you like to give the ECS that would like to stay in science?

Xavier Le Pichon – Credit: Instituto De Estudios Andinos Don Pablo Groeberg (IDEAN)

Basically, I have been an autodidact. I have always learned, in contact with other people, but mostly by myself. I cannot give any advice about what is best… but it is clear that you have to go to a place where research is thriving. If you go to a place where nothing happens, you will not start by yourself something unless you are a real genius. But even then, you don’t have the resources and so on. So you first need to identify the place where things are moving, where things are happening.

And then you try to go to this place and then, if possible, you try another one. Don’t get stuck to one thing only. Try to see the world, try to see how it moves, try to contact people…

One of the most interesting things in research is the contact with other people. Academia is a place where you have a lot of cooperation and you learn to interact with others and having a wide network of people with whom you interact is one of the gifts of this type of life. One very interesting thing is wherever you go you will agree if you talk about good science. Because when proper science is made, everybody agrees. This is not true in any other field. In philosophy, for example, you will never find people with whom you totally agree, it’s impossible. In science it’s so restricted, the rules are so clear that you are sure to come to a common agreement. So you can work with anybody on Earth that has the proper mind to do research and you will cooperate very well.

Xavier Le Pichon – Credit: Xavier Le Pichon

Interview conducted by David Fernández-Blanco

Shaun Price

Plate tectonics perhaps only started when our earth landmass got well above sea l level.

Whilst under the sea there may have been a lot more lubrication and as such did not cause damage that we can see easily observe