These blogposts present interviews with outstanding scientists that bloomed and shape the theory that revolutionised Earth Sciences — Plate Tectonics. Get to know them, learn from their experience, discover the pieces of advice they share and find out where the newest challenges lie!

Meeting Dan McKenzie

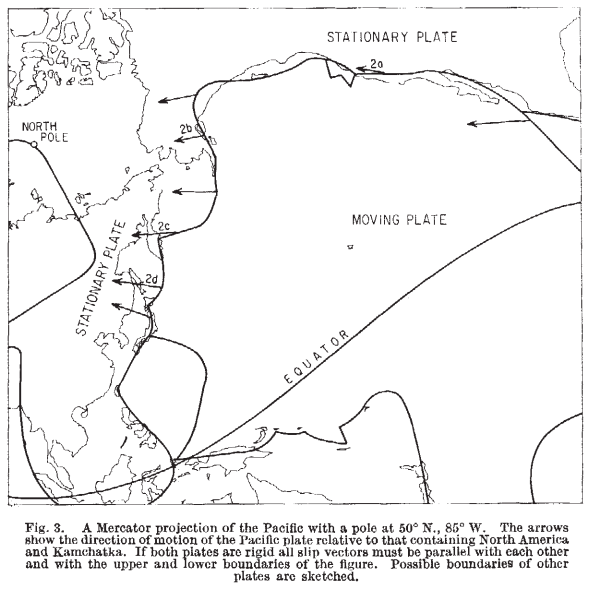

Prof. Dan McKenzie is one of the key actors empowering the Plate Tectonic Theory. He was Professor of Geophysics in Cambridge until he retired in 2012. He is mainly known to have published, together with Robert Parker, the first paper on Plate Tectonics. “The North Pacific: an example of tectonics on a sphere” describes the principles of plate tectonics, where individual aseismic areas move as rigid plates on the surface of a sphere.

The trick is to know what is tractable and also what is not understood.

You are known to have published the “very first paper” on plate tectonics. How did this contribution came about?

I was a Physics undergraduate in Cambridge. Then I became a graduate student of Teddy Bullard with whom I worked on the fluid dynamics of the mantle before it became at all understood. He got me to a conference in New York, where I heard for the first time all the works that Vine had done on, eventually, plate movements. While examiners were reading my PhD, I did the work of my first paper on plate tectonics. It was concerned with the thermal consequences of plate creation on ridges. In Summer 1967, I went to Scripps and there I was reading a paper by Teddy on fitting the continents. It occurred to me that the method he used, Euler’s theorem, actually was a way to describe all surface motions of the Earth. And so I did. I wrote, what then turned out to be the first paper on plate tectonics, which was published 1967. I don’t have priority. Jason Morgan gave a talk at the AGU in the Spring of 1967. But his abstract was completely different from the talk he gave. I had read his abstract not too long before he gave the talk, and I missed it. It made no impression at all on the AGU.

Since then, I worked a bit on Plate Tectonics, but it became quickly a dead end. I was intrigued by some observations from ocean Islands, which showed that their sources had been isolated from the convecting of the mantle for about a thousand million years. This seemed extraordinary to me! So I got interested in the whole question as how you generate melt. I worked on that for quite some time. I’m still working on that.

I have gone beyond my wildest dreams

I worked on a lot of areas in the Earth Sciences and I have gone beyond my wildest dreams (laughs). It never occurred to me that I would be given all this prices and funding –it is all very flattery! But I am always amazed by the fact that my papers are read and cited.

Dan McKenzie (1976) – Credit: The Geological Society (Mckenzie Archive)

How do you remember the beginnings in your career, what was your main motivation?

I never had an overall plan about what to do for my career. I simply work on what I find interesting and what I think that I and other people might be able to understand. I put my mind to it. There is no point in working on things everybody understands, nor in working on something that is totally intractable, because eventually, you won’t catch it either. The trick is to know what is tractable and also what is not understood. I particularly watched the technology. Most of what I have done followed a change in technology. You have to have some feeling that you can do something new and interesting, otherwise you are just going to get lost. If hundreds or thousands of people do the same thing, that is not the sensible thing for me to do. I have nothing to add to that. They do much better than I would. But the data is marvellous, and I can use it to do all kinds of things. The best scientific problems are clearly interesting, clearly not known and not understood, but tractable. There is no point whatsoever, trying to attack problems that are not tractable.

[Plate Tectonics research] was frankly a bit of a disappointment

What would you say, has been the favourite aspect of your research?

I think the one that had the most influence on my career was certainly plate tectonics. That was frankly a bit of a disappointment. It was so successful that it really needed no further work. I spent an enormous amount of energy in the 1960’s in trying to make the theory as simple and as obvious as I could. And I succeeded, and other people were part too, but we succeeded too well (laughs). And it did become really routine. Since that time, there haven’t really been any changes. So, it isn’t my favourite at all!

My favourite is trying to understand the mantle convection (of which plate tectonics is one aspect). Trying to understand the fluid dynamics of mantle convecion is really the dominant aspect of the research I have done for fifty years.

I am driven by wanting to understand things, rather than by the uses that people make of my understanding

After all the time you have spent in science, where do you see the biggest challenges right now in your field?

Dan McKenzie (mid 1990s) – Credit: British Library (Voices of science)

The present surface of Mars is so thick that it isn’t actually moving, but it seems it did in the past. So probably, in the early history of Mars, it did have something like Plate Tectonics. And I am sure that, if and when we ever get good images, the works on fluid dynamics will actually give us a handle of what is happening on this and other planets. But you need extraordinary increased spatial resolution images to actually see what is happening on planets in the solar system.

You have contributed greatly to establishing the revolutionary Theory of Plate Tectonics. Still, one might wonder – what are the real-world applications of your research?

McKenzie & Parker (1967). Nature, 216(5122), 1276–1280.

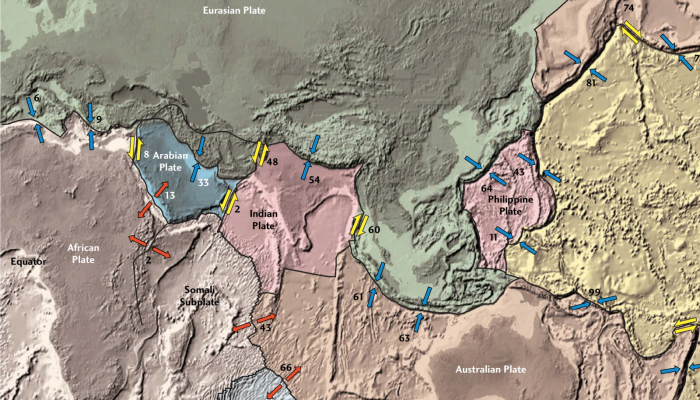

The understanding of plate motions has completely changed our views on seismic risk. At present, I think GPS is an enormous step forward in our understanding of seismic risk. Now, you can actually see the elastic strain that accumulated on plate boundaries using GPS. For instance, Tibet is moving southwards with respect to India. But there have been no really big earthquakes along the Himalayan front in historical times. It is quite clear from the GPS that there have been huge but very infrequent earthquakes. What has been happening in Indonesia and also in Japan, is likely to happen here: it will unzip and there will be earthquakes. I wish the Indians would take it more seriously… My friends and I reckon that somewhere in central Asia this century there will be earthquakes which will kill millions of people. That is a frightful thought.

…somewhere in central Asia, this century there will be earthquakes which will kill millions of people, and that is a frightful thought

The thing I have done that had the most economic impact is getting an understanding of how oil is produced in sedimentary basins. That is a paper in which I put together our understanding of how such basins were formed. Which is simply by stretching of the continental crust. It is not like Plate Tectonics, because the extension is not localised, but distributed. That was the key. It took us long to understand that because we were actually trying to think in terms of plate motions, or plate boundaries. The paper is six pages long but no one ever reads the second three pages (laughs). If I had written only three pages, it would have had the same impact…

What I am doing now doesn’t have the same impact… Understanding mantle convection beneath the plates is not going to be of nearly the same significance, frankly. It is fascinating to see how it works, but it is a different matter. I am driven by wanting to understand things, rather than by the uses that people make of my understanding.

Well, it will come to a use eventually!

Yes, understanding can be always be used… for good and bad reasons… look at nuclear physics.

Rather than more support, there should be less support

After being many years active in the academia, what would you change to improve how science is done in your field now?

This is not a question I ever thought about… I think my answer to that will be a bit complicated…

The real danger, in all subjects, is that the bright young people have lots of opportunities to be a graduate student and to obtain a PhD. And then they get trapped. They are not really good enough to get a proper tenure position in a university. But they are basically good enough to get a postdoc. They discover quite late in their careers, sometime in their thirties, that this is not going to work, that they are not going to get any further. And then they have real crashes. I think there is too much encouragement, on the funding agencies particularly, to carry people to keep on doing postdocs. This is really quite unfair. These people are really clever and they could have a much better career. How do you stop people from doing this, I do not know. Rather than more support, there should be less support (laughs). Of course, the people employing the postdocs, the tenured staff, object very strongly to this. Scientists, once they get a tenured position, want someone to do the work. They got the grant to employ people. They get the credit.

Get out of [academia]!

So, taking this you just mentioned into account, what advice would you give to Early Career Scientists?

Get out of it! (laughs). Unless you have very good chances to get a good position, get out of it and do something else before you get too old! That is what I always tell.

My career is of no use whatsoever to anyone

When you were an Early Career Scientist, did you always see yourself staying academia? What were your career expectations in that sense?

To be honest I did not think about these things… My position was rather particular. I wrote the first paper on Plate Tectonics at age 25. And I reckoned I was going to get a job! (laughs). So, I did not worry too much about that. When I was offered a job, I was offered a position at Cambridge, a full professorship at Manchester and one of the grand professorships at ETH in Switzerland. All at the same time! (laughs). I chose to stay in Cambridge and got married. For some time I was very poor, but I reckoned that would change. And it did. I never really worried about money. My career was not in any way planned and is no guide to anyone. Nothing like Plate Tectonics has happened since, it was really singular. So my career is of no use whatsoever to anyone. Things were different. When I started, there were almost no postdoctoral positions…

Dan McKenzie (2014) – Credit: Cambridge University

Interview conducted by David Fernández-Blanco