In recent months, I had the opportunity to work on a project analysing subsurface data from a rock sequence previously interpreted as the product of an estuarine depositional environment. The client sought subsurface maps to characterize the spatial distribution of various geobodies associated with sedimentary deposits typically found in modern estuaries. In other words, the goal was to reconstruct the sedimentary architecture of the subsurface beyond seismic resolution, identifying geobodies that cannot be resolved through seismic surveys.

This task was particularly challenging due to our limited understanding of what estuarine deposits preserve in the subsurface. This knowledge gap is somewhat surprising, given that estuaries are relatively accessible for study compared to other environments where physical conditions hinder direct observations and data collection, such as deep-marine settings with extreme hydrostatic pressure or river systems with strong, continuous currents. In estuaries, currents are still present but typically reduced by the expansion of the waterbody from a river channel into a network of channels bounded by sand bars and marshes. The reason for this knowledge gap is clear: we lack enough studies of ancient outcrops from estuarine environments. In this article, I will show examples of ancient estuarine outcrops and discuss a few key takeaways from their deposits.

Understanding Estuarine Dynamics for Outcrop Interpretation

Before diving into ancient outcrops, it is crucial to understand how estuaries function and how their deposits form. Estuaries are highly dynamic coastal environments where freshwater from rivers meets and mixes with saltwater from the ocean. The interplay of riverine, tidal, and coastal currents, along with wave action, makes estuaries among the most complex sedimentary environments in nature.

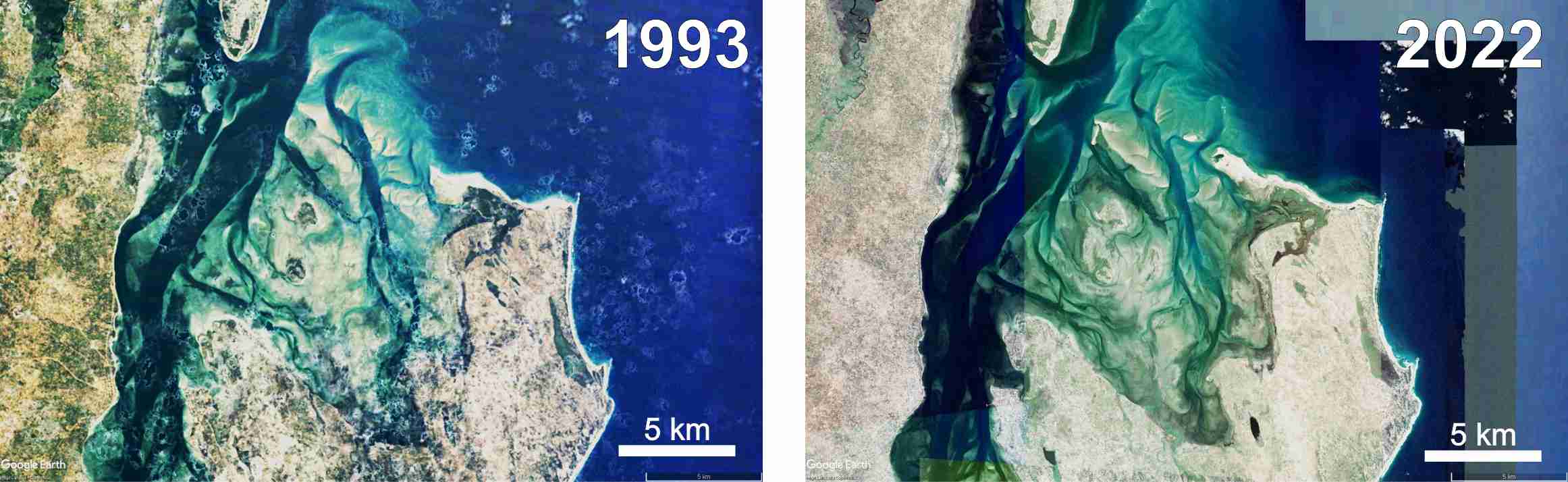

One of the most dynamic zones of an estuary is its mouth. Here, sediment transport processes create two primary deposit types: sand bars and sand dunes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The internal architecture of sand bars (above) and sand dunes (bottom figures) in modern estuaries.

Observing Modern Estuaries: Insights from Satellite Imagery

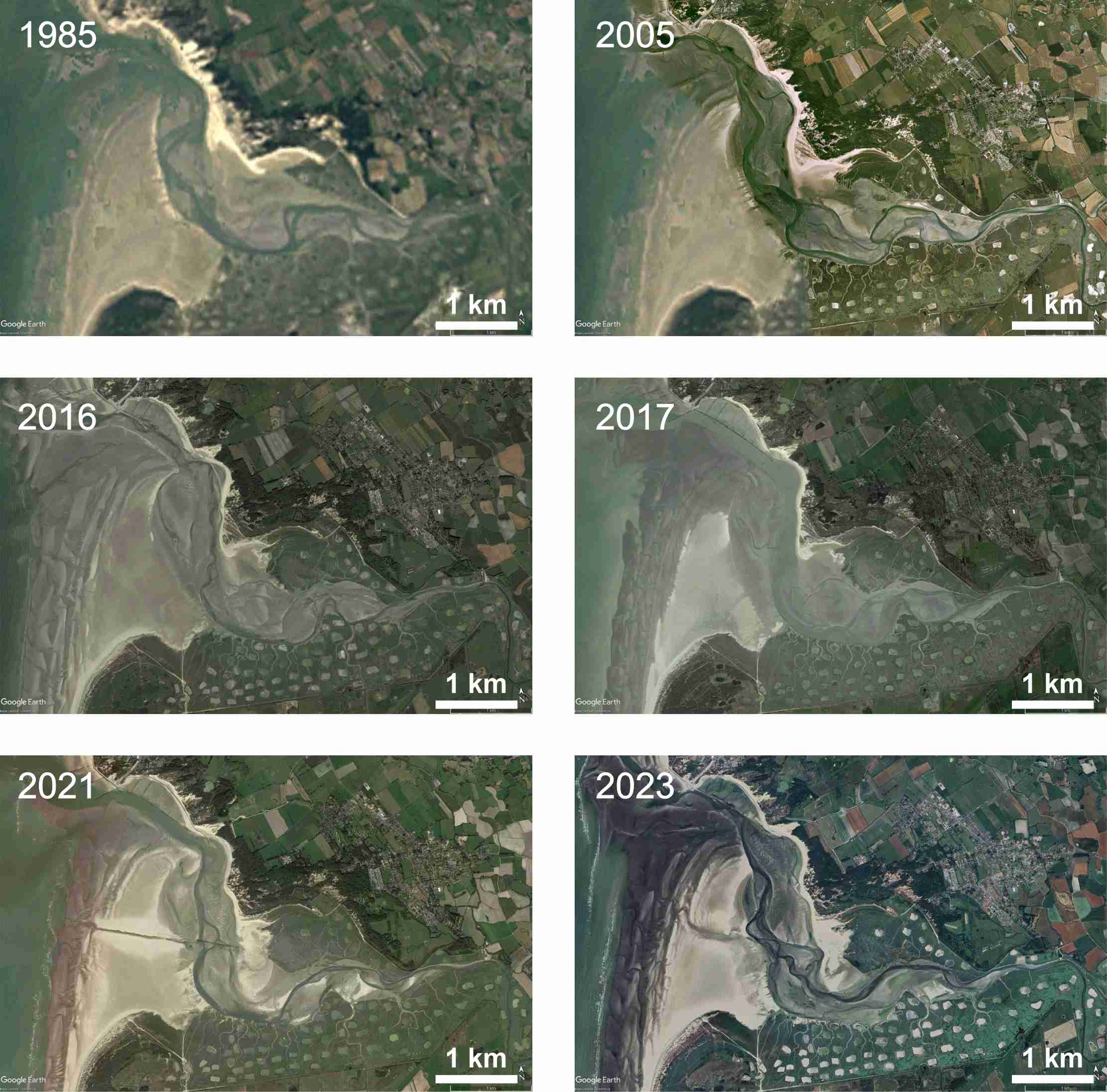

Thanks to satellite imagery, we can observe the continuous geomorphological changes occurring at estuary mouths by tracking the shifting positions and dimensions of sand bars, sand dunes, and tidal channels. For example, the Authie Estuary on the west coast of France is a relatively small estuary where sand bars and tidal channels can shift within days or even hours, depending on atmospheric, tidal, and fluvial conditions (Figure 2). Over nearly 40 years, its geomorphology has undergone multiple transformations.

Figure 2. Satellite images of the Authie Estuary on the west coast of France from 1985 to 2023. Source: Google Earth

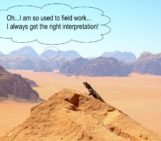

In contrast, larger estuaries tend to show a slower rate of geomorphological change. The Inhambane Estuary on the west coast of Mozambique (Figure 3) exhibits a more stable configuration of sand bars and tidal channels over a 30-year period. However, from a geological perspective, even these seemingly stable estuaries are subject to inevitable long-term change. In the end, all estuary mouths experience sand bar migration. Only changes the timescale, which can range from years to several decades.

The Preservation of Estuarine Deposits in the Geological Record

The pervasive migration of bedforms has direct implications for the preservation of estuarine deposits. Remnants of sand bars, and to a lesser extent sand dunes, can become preserved in the stratigraphic record through various processes, for example:

- Subsidence: The area subsides, allowing new sand bars to form on top of older ones.

- Sea-Level Drop: A drop in sea level leaves the former estuary in subaerial conditions

- Sea-Level Rise: Marine sediments deposit over the estuarine deposits.

These processes can result in the “fossilization” of sand bars and sand dunes in the subsurface only if erosion does not occur thereafter.

Studying Ancient Estuarine Deposits: Outcrop Analogues

To best study preserved deposits from any depositional environment, ancient outcrop analogues provide the most detailed and accurate information on facies distribution and geobody dimensions. While seismic and well data offer valuable insights, they lack the resolution needed to capture the full complexity of sedimentary structures.

However, not all outcrop analogues are equally useful. Ideally, an excellent outcrop analogue should expose continuous stratigraphic sequences both laterally and vertically over hundreds of meters. Several case studies meet this criterion, but most of them describe sand bars from interpreted deltas, incised river valleys, nearshore shoals or tidal straits (e.g., Olariu et al., 2012; Legler et al., 2014; Sleveland et al., 2020). Sand bar fields inside estuaries are almost absent in the scientific literature.

Over the past few years, I have had the privilege of studying an exceptional outcrop analogue of an estuary in the La Popa Basin, north-eastern Mexico. This estuary, which existed during the Eocene in the proto-Gulf of Mexico, crops out sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone sequences that are continuously exposed for hundreds of meters vertically and several kilometres horizontally (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The Viento Formation consists of sandstone packages with sedimentary structures, ichnofabrics and biostratigraphic content compatible with estuary environments.

Insights from La Popa Basin: Dominance of Sand bar Deposits

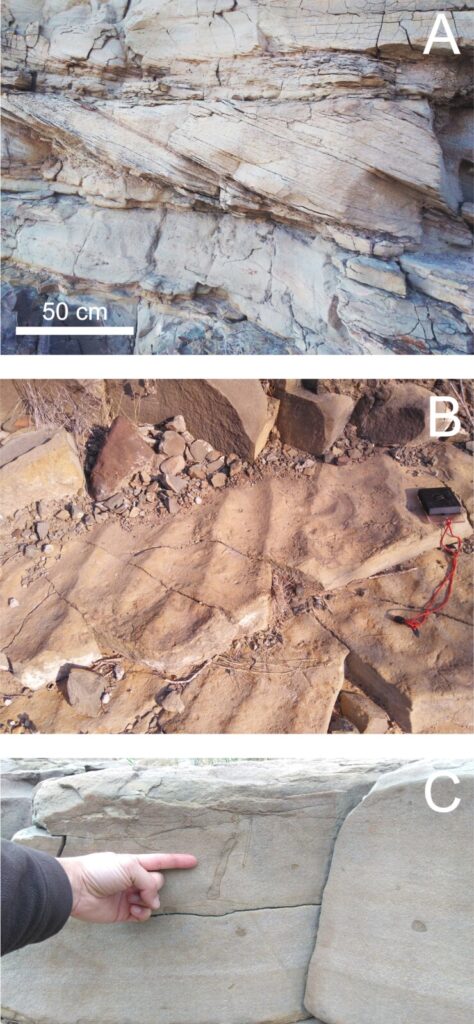

The La Popa Basin outcrops reveal a striking dominance of sand bar deposits over other estuarine deposit types. Abundant sand dunes with classic ripple marks and well-developed intertidal ichnofabrics are also present (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Outcrops from Viento Formation in La Popa Basin, Mexico: A) Cross-bedded sandstones interpreted as the remnants of sand bars; B) Undulatory ripples on top of cross-bedded sandstones (sand bars); and C) Ichnofabrics from estuarine organisms which burrowed into sand bars.

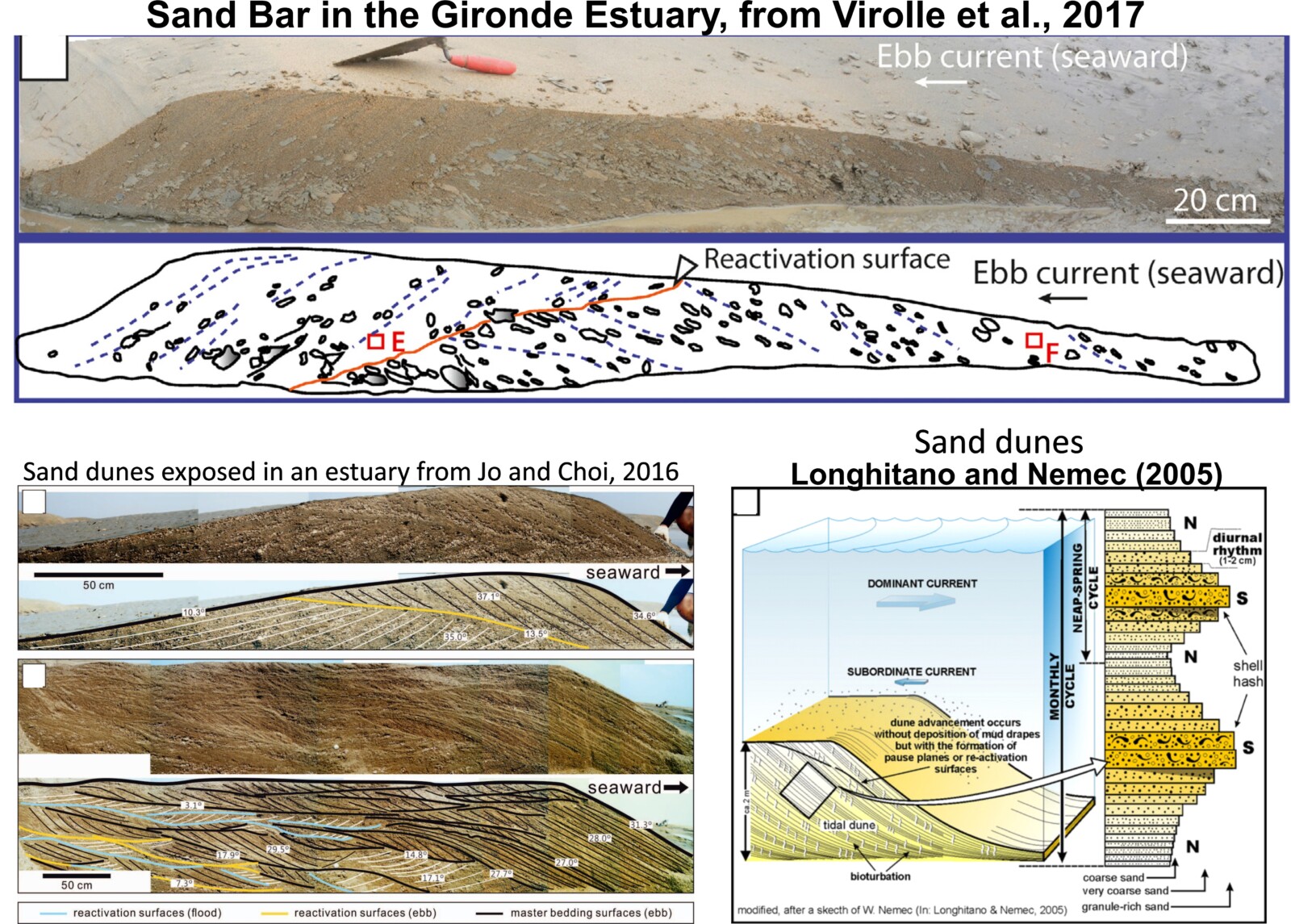

But what about the tidal channels we observe in modern estuaries such as Authie and Inhambane? Interestingly, channel-fill deposits are scarcely preserved compared to sand bars. The classic model of a channel-fill consists of a concave-up erosional surface overlain by onlapping beds, sometimes forming sigmoidal morphologies at the channel margins (interpreted as point bars in meandering channels). However, such features are rarely observed in ancient estuarine outcrops (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Tidal channel-fills interbedded by cross-bedded sandstones (interpreted as sand bars). The channel-fills are the reddish lens-shaped areas in the centre of the image.

Explaining the Scarcity of Channel-Fill Deposits

The relatively rarity of preserved channel-fill deposits can be explained by the extensive sand bar migration observed in modern estuaries. Over time, tidal channels are frequently reoccupied by migrating sand bars, preventing the formation of classic channel-fill architectures. This appears to be a general rule for estuary mouths dominated by sand bar fields but may not apply to the inner parts of estuaries, where tidal currents are weaker and channel-fill deposits may have a better chance of preservation.

The Need for Further Study

The La Popa Basin case study provides valuable insights into the preservation of estuarine deposits in the subsurface. However, much remains to be understood. Continued study of modern estuaries, across a wide range of settings, will refine our ability to interpret ancient estuarine deposits. The more we understand modern processes, the better we can reconstruct the sedimentary history of past environments preserved in the geological record.

References Jo, J., & Choi, K., 2016. Morphodynamic and hydrodynamic controls on the stratigraphic architecture of intertidal compound dunes on the open-coast macrotidal flat in the northern Gyeonggi Bay, west coast of Korea. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 86(10), 1103-1122. Legler, B., Hampson, G. J., Jackson, C. A., Johnson, H. D., Massart, B. Y., Sarginson, M., & Ravnås, R., 2014. Facies relationships and stratigraphic architecture of distal, mixed tide-and wave-influenced deltaic deposits: Lower Sego sandstone, western Colorado, USA. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 84(8), 605-625. Longhitano, S. G., & Nemec, W., 2005. Statistical analysis of bed-thickness variation in a Tortonian succession of biocalcarenitic tidal dunes, Amantea Basin, Calabria, southern Italy. Sedimentary Geology, 179(3-4), 195-224. Olariu, C., Steel, R. J., Dalrymple, R. W., & Gingras, M. K., 2012. Tidal dunes versus tidal bars: The sedimentological and architectural characteristics of compound dunes in a tidal seaway, the lower Baronia Sandstone (Lower Eocene), Ager Basin, Spain. Sedimentary Geology, 279, 134-155. Steel, R.J., Plink-Bjorklund, P., Aschoff, J., 2011. Tidal deposits of the Campanian Western Interior Seaway, Wyoming, Utah and Colorado. In: Davis, S., Dalrymple, R.W. (Eds.), Principles of Tidal Sedimentology, pp. 437–472. Virolle, M., Brigaud, B., Bourillot, R., Féniès, H., Portier, E., Duteil, T., and Beaufort, D., 2019. Detrital clay grain coats in estuarine clastic deposits: Origin and spatial distribution within a modern sedimentary system, the Gironde estuary (south‐west France). Sedimentology, 66(3), 859-894.