Smoky Summer

It has been a difficult summer in Alberta, with smoke from forest fires in British Columbia blanketing much of the southern part of the Province. However, this has not stopped me getting out into the field on a variety of projects and hikes, including a virtual field trip looking at the Cardium Formation and several in person trips to the beautiful Sheep River Provincial Park and surrounds. I have also signed a contract to act as Consultant Palaeontologist to a service company specializing in site investigation, which will hopefully bring in some interesting work. When not working, we have also camped out at some classic geological sites including Kananaskis, Lake Louise, Cypress Hills and Dinosaur Provincial Park, as well as looking at similar sediments exposed in eastern Alberta. All this activity has certainly made me realize how fortunate we are here to have so much breathtaking geology on our doorsteps, so I decided to share some highlights here.

- t=Trough cross-bedded sandstone from the Cypress Hills Formation, eastern Alberta

- Bow Falls in Jasper National Park, flowing over fossiliferous Devonian limestone

Bow Glacier Falls are sourced from the Bow Glacier located above them, which is an outflow glacier from the Wapta Icefield. The scarp over which the Falls cascade is made up of Cambrian sediments, which are described in more detail below, in the final section of this blog. The water from the falls flows into the Bow River, making its way through part of the Rockies and across the Foothills and Prairies to Calgary. The trail to the Falls passes an outwash braid plain, ascends a steep path with a precipitous drop into the gorge created by the rushing waters, and crosses a bleak terminal moraine littered with glacial till. The trailhead begins 40 km north of Lake Louise.

Conferences

Two of Calgary’s premier geology conferences ran as virtual events this year, no replacement for in person events but better than no conference at all. The Core Conference was rolled out in May, with presenters providing a general talk, a core focused talk and a poster. In 2020 I bought some United Kingdom cores from the excellent (not for profit) North Sea Core (North Sea Core | Home) and decided to present on these cores to show the diverse depositional settings encountered in the North Sea. The cores include Carboniferous (fluvial, floodplain and crevasse splay examples); Rotligendes (aeolian dune, interdune, playa lake) and Brent Group, Jurassic cores. The latter featured hummocky cross-stratification from the Rannoch Formation and Back barrier lagoonal sediments from the Lower Ness, as well as cores from each of the Brent Group Formations: Broom, Rannoch, Etive, Ness, Tarbert, with the initial letters spelling B-R-E-N-T. I was lucky enough to win the Pemberton Award for best presentation. My poster is shown above, while my talk is located on my YouTube channel – click on the link below to view it.

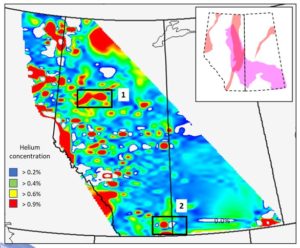

The second conference was Geoconvention 2021. This features a wide variety of technical talks from industry and academic, with a bias towards oil and gas related themes. I took the chance to present on the Exshaw Shale, a potential Bakken equivalent from southern Alberta; on helium, discussing the fallacies swirling about this resource; on the fluvial Lisama Formation, a Paleocene reservoir from Colombia; and a fun talk on unusual approaches to sedimentology. Alberta holds significant Helium reserves, and these can be highlighted by crunching gas composition data from some of the 800,000 wells drilled across the Province. Helium typically migrates into shallow reservoirs from deep seated, radioactive, igneous rocks and can be produced along with natural gas.

The video for my talk: “Turning Geology Upside Down” can be found here (free to view):

Consulting Palaeontology

Thanks to the laws relating to ancient resources in Alberta, I have had the good fortune to be helping two companies with site monitoring. Ongoing projects include a new dam being built near Bassano; a new subdivision with around 600 new homes in northern Calgary; and a pipeline project to the west of Edmonton. The dam project will flood around 30 kilometres of prairie, with some limited outcrops of the Bearpaw Shale. These yielded some nice pieces of ammolite, a rare, iridescent, gem-quality material coating the fossilized shells of ammonites. The building sites of northern Calgary are being excavated in terrestrial Paleocene sediments, with channels, lakes and overbank deposits containing plant, molluscan, reptilian and rare mammal remains.

We encountered some fascinating glacial sediments along the pipeline route. Many of the channel sands were rooted, with the individual roots cemented by siderite. There were trough cross-bedded horizons but no obvious lateral accretions surfaces, indicating that these were braided to low sinuosity channels rather than meandering channels, probably deposited ion an outwash plain. The rarity of overbank muds indicated that accommodation space was limited, while glacial gravels were only observed in one section of the trench, possibly due to local changes in the flow regime.

Sheep River Provincial Park

This Rockies Foothills region, some 100 kilometres southwest of Calgary, is much less frequented than the neighbouring Kananaskis region. As such, it is an excellent venue for field trips, including a “Source to Sink” themed trip that visits several fluvial outcrops, both braided and meandering; a coastal outcrop; and two shallow marine successions. The coastal outcrop (earliest Jurassic in age) has fairly thick coals which have taken up much of the tectonic stresses, exhibiting cleavage and folding. They are overlain by thick channels deposits. At first glance these look to comprise a series of stacked channels, but careful mapping demonstrates that these are lateral accretion surfaces within a single, 10 to 15 metre thick, channel. The coals suggest that this channel is estuarine, subject to tidal forces, while the sand produces gas in the subsurface in this area.

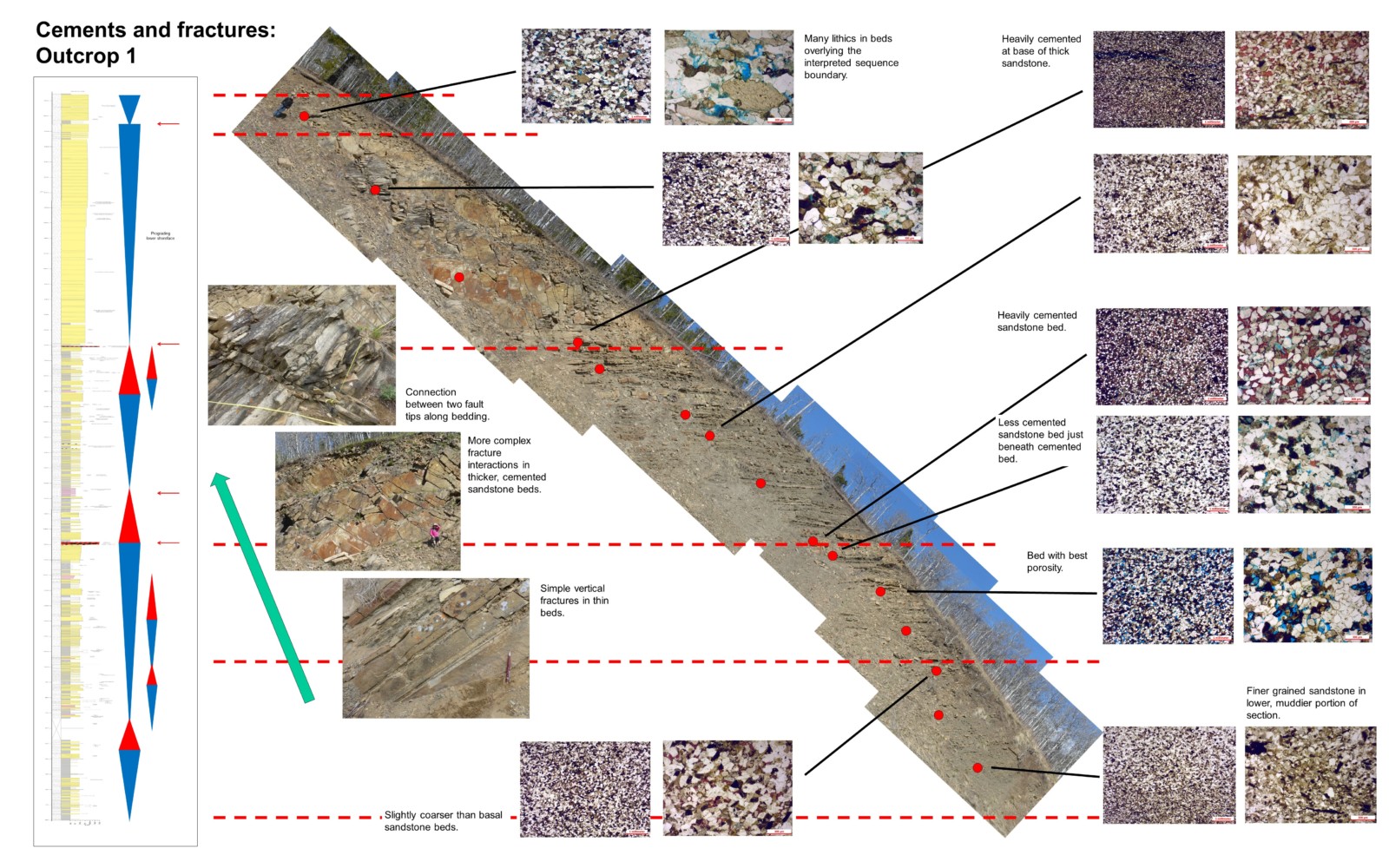

Poster showing a tilted image of the Virgelle Member outcrop – the shoreface section is around 47 metres in thickness. Thin sections and a sedimentological log are also featured.

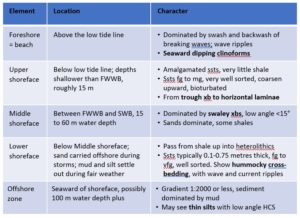

Shoreface deposits from the Virgelle Member, Milk River Formation (around 90 million years old) also feature on the field trip. They show a series of coarsening upward sequences, interspersed with at least three transgressive surfaces of erosion (TSEs). What is nice about this outcrop is that we have measured sedimentological logs; gamma ray data (collected using a scintillometer) and thin sections, which can be integrated to help with discussions on reservoir development and character. I have run three field trips here over the summer.

Exploring the Cardium – not for the faint hearted

Taking on new lines of research exposes you to new geology. This month I agreed to give a virtual field trip (VFT) to outcrops of the Cardium Formation. These sediments were deposited in dominantly shallow marine conditions on the western margin of the Western Epicontinental Seaway, which stretched from the Arctic Circle to Texas and beyond in the Cretaceous. The Seaway was formed as a retro forearc basin in front of the proto Rockies as the Pacific Plate was subducted under the Canadian Shield. The Turonian Cardium Formation makes up the main reservoir in Canada’s largest oil field, the Pembina Field in Alberta, which holds at least 1.6 billion barrels of oil. The main reservoirs are either sand prone, stacked sandy parasequences or conglomeratic packages, the latter interpreted as pebbly deposits reworked from the mouths of rivers.

I needed to shoot some videos for the VFT which led me to some new and some established outcrops. I visited the stunning Ram Falls, three hours NW of Calgary and involving two hours of negotiating nerve jangling winding dirt roads through the Rockies. The Falls cascade over a 15 metre thick succession of marine sandstones, the Karr Member of the Cardium. Access to outcrop is tricky but I was able to film some heterolithic, lower shoreface deposits which are analogues for the subsurface “halo play”. Most of the existing Cardium oil production has come from the thick sandstone and conglomerate reservoirs, but in 2008, small companies began targeting the fringes around these sandbodies, utilizing unconventional reservoir techniques like horizontal wells and fraccing. These halos of thin, storm generated sands typically produce around 150 barrels/day (IP90 = initial production over the first ninety days), dropping to 20 barrels/day over the first year.

While at the Falls I also investigated the overlying Wapiabi Shale package, with black organic rich shales reaching 400 metres in thickness. I trekked up a side gully and met a fossil hunter who explained that ammonites could found in nodules around 2/3 of the way up the slope. The very steep dips were pretty scary, but I managed to find a beautiful Scaphites ammonite. These fossils are excellent index species. The other highlight was watching a male bighorn sheep (the “Ram” of Ram Falls”), confidently making his way across very steep slopes just above the cliffs fringing the waterfall. Rather him than me!

- Scaphites ammonite exposed in the Wapiabi Shales

- Bighorn Sheep ram at Ram Falls

View of the steep sided Ammonite Gulch. The fossils occur just above the cemented layers, half way up the exposed faces in the Wapiabi Shale

Zooming in on Shorefaces of the Cardium Formation

Another famous Cardium outcrop is located at Seebe Dam, some 90 kilometres west of Calgary. Once again, the thick, resistant sands of the Cardium form falls and rapids. The noise of the water does not help with filming, even utilizing the new radio mike, but I was able to capture some textbook parasequences. Each one represents a phase of coastal progradation, with a shallowing and coarsening upward package, capped by a flooding surface:

There are striking changes from thinner to thicker beds; from fine to coarser grained sands; from hummocky to trough cross-bedding; and from Zoophycos to Rhizocorallium trace fossils (beautifully exposed on bedding planes at Seebe), as one ascends each parasequence. The thickness of these parasequences typically ranges from 2 to 7 metres, and each one is capped by a thin, transgressive, conglomeratic lag formed during rapid sea level rise flooding over the shallow marine sands. The Hornbeck Member is capped by starved gravelly dunes that have been cemented by orange siderite, while the upper surface of the Raven River Member is heavily bioturbated. The trough cross-bedded deposits are best exposed at Seebe North Quarry, located just below Mount Yamnuska, with more breathtaking scenery and some great geology to boot. LaFarge and Transalta are thanked for allowing access to these outcrops.

- Shoreface parasequences beautifully exposed at Seebe Dam, Alberta

- Trough cross-bedded sands from the Chungo Member, Wapiabi Shales, Yamnuska Quarry, Alberta

- Rhizocorallium, a striking shallow marine trace fossil with paired tubes and spreite

And finally…

My geological highlight over the last few months would have to be the extraordinary stromatolite beds at Helen Lake. The trailhead is located opposite the Crowfoot Glacier on the Icefields Parkway, although the “foot” was barely visible in the wildfire smoke. We hiked up to Helen Lake and then followed a winding path up the escarpment on the plateau below Cirque Peak. At the top, the outcropping sediments are part of the Middle Cambrian Pika Formation, named for Pika Peak near Lake Louise. The upper portion of the Formation appears to be carbonate dominated, and at the top of this interval is a well developed bed of stromatolites.

These are layered accretionary structures formed in shallow water by thin films of cyanobacteria. The sticky algae traps sedimentary grains, gradually accumulating matter over time leading to upward growth. You first encounter a few weathered dome shaped examples, but tracking northward a field of exposed, in situ domes is exposed. The domes are elongated in shape suggesting a tidal influence, and with a little imagination you can picture yourself in Hamelin Pools in Shark Bay, Western Australia, where the world’s best living stromatolites can be viewed.

You can see a short video showing the stromatolites here:

In summary

Today’s blog has been written to show the enormous geological diversity sitting so close to Calgary. In one direction we have the majestic Rocky Mountains, and in the other the Prairies with picturesque badlands and glacial morphology and outcrops. When restrictions on travel are lifted, I urge every geologist to come and revel in the geology of these outcrops.

FoodDoz

Thanks for the blog. https://www.fooddoz.com/

Jonathan (Jon) Noad

My pleasure 🙂

karahan

Great Post

FoodDoz

Thanks for the blog. Best regards.

https://www.fooddoz.com/