![Fire, Fog, Frost, Famine – French Revolution? The Lakagígar eruption in Iceland, 1783-1784 [Part 2]](https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/gmpv/files/2018/05/banner1-2-700x400.jpg)

PART II: Were the Haze Hardships caused by Men?

Famine

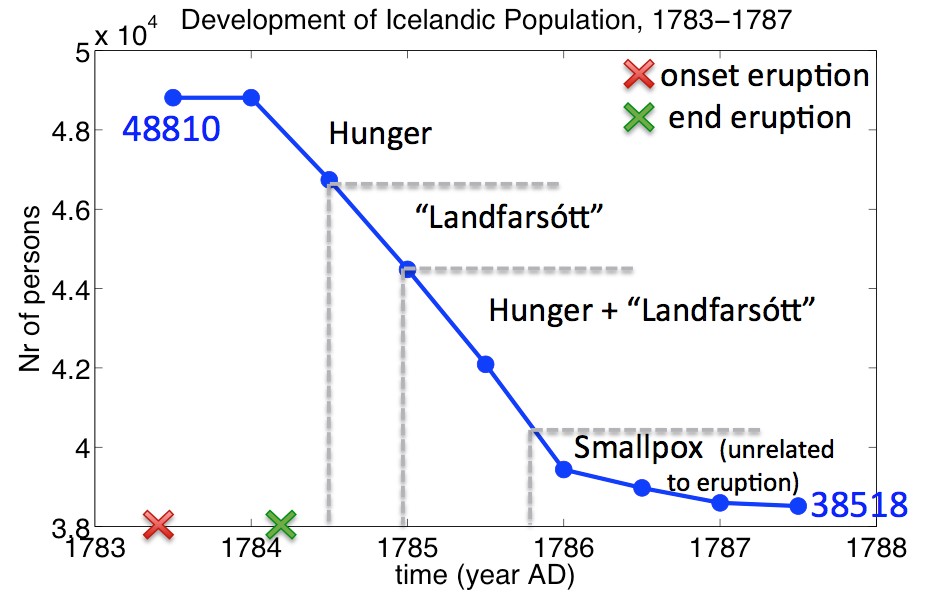

Before the Lakagígar eruption, the population of Iceland was 48810 people; four years later, it was down to 38518. Disregarding about 1500 deaths which were caused by a smallpox epidemic, the eruption may still have killed about 1/6 of the population [5]. These deaths were not directly caused by the lava or by toxic gases. The main cause was hunger. Having lost their sheep and cows, people cooked shoes and leather ropes, and even dug up old fish bones from the rubbish heaps. But it was not enough.

“From the time the eruption started until New Year 1784, the death rate caused by its poison was not so high”, wrote Reverend Jón Steingrímsson [1], “but from New Year onwards, it grew more and more…” With only one surviving horse in the whole parish, it became difficult to bring the dead bodies to the church, and the enfeebled people were hardly able to dig the graves. On certain Sundays those who could still walk would gather at the church, hack a hole through the frozen earth, and bury all the coffins from the previous week in a single grave. The famine not only affected the parishes close to the Lakagígar but took hold across most of the country.

The Icelandic population between 1783 and 1787. It is not exactly clear what historical sources mean by “Landfarsótt” (literally “illness travelling through the country”), but is has been argued that people were succumbing to normally harmless diseases because they were weakened by hunger. Data taken from [5].

The fish and sheep paradox: a society primed for disaster?

Denmark was an absolutist monarchy but the king was mentally ill. His cabinet minister and the crown prince struggled for power and left it to the Rentekammer (finance department) to deal with Icelandic volcanoes. The officials in Iceland were reluctant to act without consent from Copenhagen, but communication was difficult. In winter, no ships would cross the Atlantic.

Iceland was an underdeveloped society constantly threatened by famine [7]. Although the island offers poor farm land, it is surrounded by a rich sea, teeming with fish. Yet, paradoxically, almost all inhabitants were farmers of farm labourers. Even distinguished parsons like Jón Steingrímsson spent their summers mowing grass, ever fearing that the cows and sheep might starve in the long winters. Several high officials recognised that developing the fishing sector was the only way to get Iceland out of poverty. In addition, fishing was less vulnerable to cold summer weather or volcanic eruptions. But despite this, fishing remained a side occupation. The fish prices were also kept artificially low by the Danish government, so in good farming years there was little incentive to fish more. And to make things worse, the relatively wealthy Icelandic landowners actively discouraged fishing as they feared losing their cheap farm labourers.

Wind-dried fish was Iceland’s most valuable export for many centuries. Image Credit: Wiki

Although in normal years the Icelanders produced enough to feed and clothe themselves, they depended on vital imports, such as wood, iron, and fishing lines. In exchange, the Icelanders offered wool products, mutton, and dried fish; the latter brought the most profit for the merchants.

The trading system hampered Iceland’s economic development but also its ability to respond to natural disasters. Trade was carried out by a group of Copenhagen merchants who had a monopoly. Their ships visited the Icelandic harbours in late spring and returned to Denmark in early autumn. Prices were fixed by the government, and although this offered the Icelanders some protection from avaricious traders and price fluctuations, in the long run, the low fish prices undermined economic development. The merchants also insisted on a barter trade rather than paying with money, this made it hard for the Icelanders to make investments or save for a bad year.

Farmers in need were entitled to get necessities – grain and tools – on credit for one year. But in spring 1783 the central government in Copenhagen felt that this rule had been abused and sent strict orders to the merchants to give fewer loans and collect outstanding debts. So when disaster struck a few months later, the trade representatives were unwilling to hand out grain on credit without further orders from Copenhagen.

Fatal inertia in Copenhagen

The first news of the eruption reached Copenhagen with the returning trade ship from Reykjavík at the end of August. It was still rather vague, mentioning the destruction of two churches and eight farmsteads as well as reduced grass growth and a strange fog. In mid-September the Rentekammer decided to send a ship to Iceland for investigation, but it had to seek winter shelter in Norway after running into several storms. The last trading ship from Iceland brought some more worrying news, but even in Iceland, the full extent of the catastrophe only became apparent through the course of the winter, when there was no means to communicate with Copenhagen. The central government decreed a collection of money on behalf of the needy Icelanders. Apart from that, no decisive measures were taken. After all, it was winter…

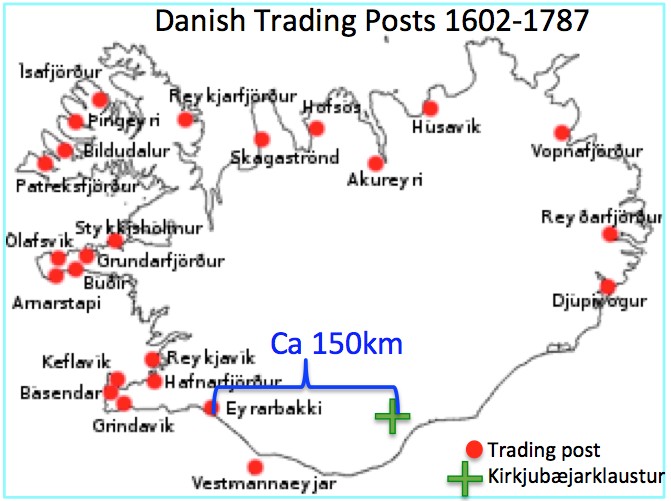

Map of the trading harbours during the trade monopoly. Note the large distance (150 km as the crow flies!) between Kirkjubæjarklaustur and the nearest trading post at Eyrarbakki. Original map from Wiki

In spring 1784, the trading ships sent to Iceland carried no additional supply of grain, even though it was obvious that there might be an increased demand for foodstuff. The investigation ship, after its winter stay in Norway, reached Reykjavík on April 16th. In mid-July, it returned with the frightful news that thousands of people had starved all over Iceland. This finally provoked some serious action in Copenhagen – 13 months after the onset of the eruption. About 500,000 kg of flour was sent to Iceland, paid by the Crown and the money collected in winter. But many Icelanders could not even collect the grain from the trading harbours for want of horses. Jón Steingrímsson complained that it would have been better to send fishing and seal catching equipment. The government also issued orders to the trade representatives to distribute the lower-quality part of the winter fish catch among the hungry Icelanders. But the orders got lost, and apparently the local Icelandic officials were unable to enforce such measures on their own. In summer 1784, a million kilograms of dried codfish was exported from Iceland – enough to provide 6000 people with sufficient calories to last 8 months. And so the famine in Iceland continued for another winter, again killing several thousand people.

The measures taken by the government – both in Denmark and in Iceland – had proven completely inadequate to prevent disaster. During the winter 1784-85, some officials in Copenhagen wondered whether Iceland was actually still inhabitable. They may have contemplated giving up the island altogether and deporting the entire remaining population to Denmark, although official protocols only speak of resettling 500-800 “unproductive” persons. Even that measure was eventually dismissed in early 1785; maybe it was deemed too costly. Meanwhile, the Danish minister of finance, Ernst Schimmelmann, considered selling Iceland to Great Britain in exchange for some tiny island in the Caribbean. But the British government was not interested in taking over Iceland, which seemed to offer no profit whatsoever. When the Icelandic economy slowly recovered after 1785, the Danes were less keen to get rid of their old dependency.

French Revolution?

It has often been claimed that bad harvests in France after the Lakagígar eruption helped to trigger the French Revolution. But despite temporary damage to plants during the hazy weeks in June and July, the harvest in central Europe remained satisfactory. The haze actually helped to protect the crops from excessive solar radiation [6]. However, the cold and snowy winter 1783/84 may have caused despair and discontent among the poor, and queen Marie-Antoinette was criticised for praising the good sledging conditions while people where freezing to death. But more than five years passed between the Lakagígar eruption and the French revolution, making a direct causal connection quite implausible [3].

The Haze Hardships also failed to bring about a much-needed economic revolution in Iceland. The trade monopoly was lifted in 1787, but trade between Icelanders and foreigners remained forbidden, and no significant development of the fishing sector occurred for decades to come. The Lakagígar eruption was a dramatic event and caused a lot of suffering, certainly in Iceland and possibly beyond; but it was no turning point in history.

Blog post written by Dr Claudia Wieners.

Claudia is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric research, Utrecht (Utrecht University, Netherlands). She did a PhD on the possible influence of the Indian Ocean on El Niño. Recently she started working on the interaction between climate, economy and policy, focusing on the potential role of (sulfur) geoengineering. She is also involved in the Centre for Complex System Studies in Utrecht.

Sources and further Reading

[1] Jón Steingrímsson’s famous account on the eruption is available for free in Icelandic: http://baekur.is/bok/000339579/4/13/Safn_til_sogu_Islands_og_Bindi_4_Bls_13. An English translation was made by Keneva Kunz under the title “Fires of the Earth”.

[2] His autobiography is available for free in Icelandic: http://baekur.is/bok/000209172/AEfisaga_Jons_profasts. An English translation with useful comments was made by Michael Fell under the title “A very present help in trouble: The autobiography of the Fire Priest”

[3] A good overview of the Lakagígar eruption is presented in “Eruptions which shook the world” by Clive Oppenheimer, chapter 12.

[4] Scientific details on the eruption and the haze were mainly taken from this paper: Thordarsson and Self, “Atmospheric and environmental effects of the 1783–1784 Laki eruption: A review and reassessment”, http://seismo.berkeley.edu/~manga/LIPS/thordarson03.pdf

[5] The description of the consequences of the Lakagígar eruption in Iceland and the intervention (or lack thereof) by the Danish government is based on this book: “Skaftáreldar 1783-1784: Ritgerðir og heimildir” (The Skaftá Fires 1783-1784: Articles and Sources) edited by Gísli Ágúst Gunnlaugsson. It is in Icelandic but has English abstracts.

[6] The consequences of the Lakagígar haze in Europe are described in Eyþór Halldórsson, “The dry fog of 1783: Environmental Impact and Human reaction to the Lakagígar Eruption”, https://skemman.is/bitstream/1946/17205/1/MA-Thesis.pdf

[7] The Icelandic Trade Monopoly is discussed in Gísli Gunnarsson, “Monopoly trade and economic stagnation: studies in the foreign trade of Iceland 1602-1787”, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3524053;view=1up;seq=37. The book also deals with the economic side of the Lakagígar eruption (chapter 9).