This year I was lucky enough to be part of International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 390 – South Atlantic Transect I – aboard the research vessel JOIDES Resolution which spent two months, from April to June, out in the South Atlantic, drilling into and sampling the upper oceanic crust and sediments. I sailed as a petrologist and was responsible for describing how the basalts which form the oceanic crust have been altered by reactions with seawater to form secondary minerals including carbonates, clays and zeolites. I learned a huge amount in the two months I was at sea, far more than I can fit into a single blog, but these are 5 snippets which together give an idea of life at sea on a big research project.

The underwater camera system being lowered into the “moon pool” at the centre of the ship down the steel drill string which extends 5km down to the seafloor

1. Ocean drilling is incredible (and incredibly hard)

Drilling the seafloor and returning sediment and rock to the boat is an incredible engineering and logistical challenge. This becomes immediately clear watching the crew on the drill floor manhandle and screw together huge steel pipes while the ship pitches in the metres high waves waves. The numbers surrounding this all are fairly astounding: at our furthest site, 9 days of transit west of Cape Town, we were drilling in a little over 5000 metres of water. That means a string of steel piping over 5 kilometres (!) long was trailing beneath the boat. At the bottom end of the drill string is attached a drill bit and rotating the entire length of pipe from a drive on the ship turns the bit, drilling into the crust and preserving a core of rock in the middle of the piping. Perhaps most remarkable is that it is then possible to get this core back to the ship by sending down a wireline which hooks into the barrel which holds the core and pulls it back up to the surface. When it arrives, the core still has the icy cold of the deep and, holding it, you feel the thrill of knowing you’re among the first people to ever look at this piece of the Earth’s crust, like you’re in on a secret.

Scientists and crew gather on the bridge as the ship comes into port in Cape Town, South Africa

2. Working in a big team is fun

The overarching aim of the South Atlantic Transect (which will be achieved by two legs of drilling – Expedition 390 and a second leg, Expedition 393 which is currently at sea) is to drill an age transect of upper oceanic crust and overlying sediments from 7 million year to 63 million year old crust all formed at the same ridge segment. This will allow us to understand how fluid and heat flow in the oceanic crust evolve with time enabling, for example, better models for carbon uptake by the crust. It will also allow much greater understanding of the deep biosphere of microbial communities in the crust and how the develop and change over time. As if that wasn’t enough, the sediment cores recovered during the cruise will enable new research into paleoclimate and ocean circulation in the South Atlantic. With all these interconnected objectives there is an absolute flurry of activity on board with sedimentologists, petrologists, microbiologists, geophysicists and geochemists all working together and collaborating to characterise the recovered cores in incredible detail. Working in that environment is really exciting and enlivening and is, I suspect, one of the things which keeps people going back to sail again and again.

Pre-dawn glow on the horizon means sunrise isn’t too far away, which means it’s not too long until lunch!

3. Salad is the best food (or: you want what you can’t have)

Life on the ship is 24/7, with most people working 12-hour shifts to keep the operation constantly running and achieve as much as possible with the time we have. With all this hard work, meal times become a real focus point of the day. A chance to unwind and chat, and to take on fuel to power you through the rest of the shift. The ship has a full kitchen and a staff of wonderful chefs who keep everyone very well fed and watered. Despite their best efforts though, after two months at sea, things inevitably start to disappear as they either go off or run out. One of the first casualties was lettuce and I was surprised at how much I missed having salad for dinner. The gradual and tragic disappearance of fresh greens was accompanied by increasing creativity to make up new and possibly ill-advised food combinations. These included houmous croissants (surprisingly good but somewhat uncontroversial), ice cream buns (unsurprisingly good but surprisingly controversial) and a series of increasingly elaborate and vertically impressive jerry-rigged desserts made by one of our co-chief scientists. To underscore the importance of food onboard, one science party member even made a ranked list of every dessert on board which, for the curious, is immortalised here.

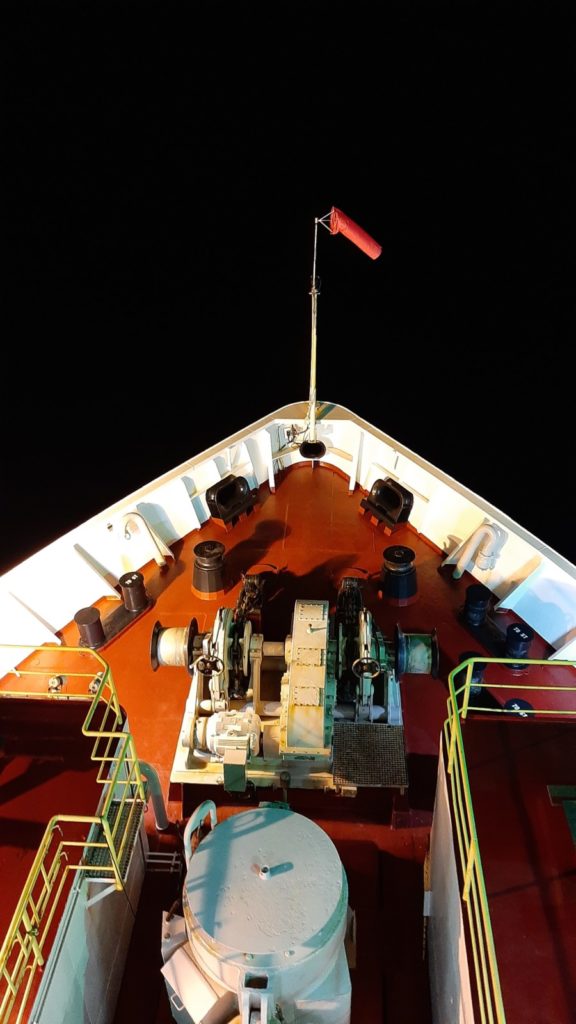

Boat to nowhere – the typical slightly disorientating view of the ship’s bow at night, apparently sailing into the void

4. It’s not so bad being nocturnal

With back-to-back shifts inevitably people are going to be working some strange hours. I was among those people assigned to the midnight to midday shift. At first this was pretty strange: waking up at 11pm and going to bed when the sun is shining outside takes some getting used to. But there were upsides too. Spending most of our waking hours in the darkness made for a sense of camaraderie and I think definitely encouraged some eccentric behaviour and a lot of (already inexplicable) running jokes. It also meant we saw some wonderful night time phenomena including a huge group of squid, a lunar eclipse, the milky way and many shooting stars. On the downside we all found our eyes really adjusted to the gloom so much that the midday sun was rather headache-inducing. At one point the decision was even taken to turn off all the lights in the petrology lab and work in the dark. Rumours of vampirism are, however, mere hearsay. All that said it was lovely to finally transition back to more normal daylight hours towards the end of the cruise, not least because it meant we could hang out with our day shift counterparts who we barely saw for much of the 2 months.

5. Expect the unexpected!

Given the complexity of the task and the leap into the unknown that comes with drilling into the seafloor, it perhaps goes without saying that it was important in to expect the unexpected. This was nowhere truer than in the rocks we recovered. They were by turns beautiful, complicated and often somewhat confounding. While I can’t reveal too much about the ongoing science because all our results are under a post-cruise moratorium, the cores did not always fit with our expectations of what we’d recover. While that of course makes some of the job of understanding heat and fluid flow and hydrothermal alteration more complex, it’s also very exciting and opens up new avenues of research which I’m very excited to get stuck into.

Rough seas in the South Atlantic – bad weather is a constant worry and one big storm forced us to leave the drill site for a few days

The second leg of the South Atlantic Transect, Expedition 393, is currently at sea. For updates on their progress follow @TheJR on Twitter or visit https://joidesresolution.org/ where you’ll also loads of information on virtual ship tours and blogs. For the scientific prospectus for the project and preliminary summaries of the scientific results from each site see https://iodp.tamu.edu/scienceops/expeditions/south_atlantic_transect.html and for information on how you can apply to sail on future expeditions, see https://iodp.tamu.edu/participants/applytosail.html. Feel free to get in touch with me by email or on Twitter if you have any questions about joining an IODP expedition or life at sea.

Nazrul I. Khandaker

Dr. Carter’s experience involving International Ocean Discovery Program will certainly pique the interest of many geology professionals and students. Working out of one’s comfort zone with a diverse group of geoscientists can be intimidating and warrants firm commitment and self-discipline to stay on track. Being a team player who is willing to learn, take criticisms, and contribute to research goals can effectively enable the working experience to be enjoyable and memorable. An experiential learning opportunity is the best platform to allow participants to further their understanding of the broader aspects of marine geology and value applied experience. The in-situ outcomes pertaining to core inspections, structural complexities and contemplating about petrogenesis can be very thrilling and rewarding. Carter’s brief synopsis sums it up very eloquently; “with all these interconnected objectives there is an absolute flurry of activity on board with sedimentologists, petrologists, microbiologists, geophysicists and geochemists all working together and collaborating to characterise the recovered cores in incredible detail. Working in that environment is really exciting and enlivening.”