And here we go, with the second part of “Volcanoes and Wines”! In Part 1 blog post we introduced you to the inevitably bond between wine and geology, with a focus on volcanic areas and minerals. We are sure we left you with a taste of volcanic soil in your mouth, wondering where you can savour red and white glasses of wine at the foot of a volcano.

Today we introduce you to some unusual and spectacular volcanic areas, which we are sure will catch your interest.

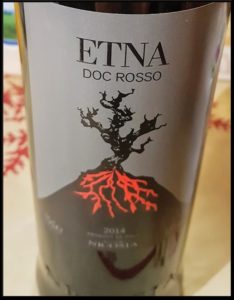

Etna wines

Mount Etna, besides giving us spectacular eruptions, is known also for its great wine production. One of the two grapes growing on its slopes are the Carricante, believed to be present for more than 1000 years on the volcanic flanks, and used to produce the Etna Bianco, and the Nerello, a red wine grape used for the Etna Rosso.

In addition to Carricante and Nerello, another main grape variety that grows in the proximity of this giant volcano is the grape Catarratto (Thomaidis et al., 2021).

One of the advantages of growing a vineyard on a slope of an active volcano such as Etna is the preservation of the soil fertility and the conservation of those precious properties of volcanic soils for longer periods of time. This happens thanks to the ash produced during the eruptions, which fertilises the soil. Indeed, the continuous input of volcanic ash provides fresh and easily weatherable material that recharge the soil with nutrients (Dahlgren et al., 2004; Delmelle et al., 2015).

This process counteracts the erosion and the chemical weathering which tend instead to consume the properties of the soil (Dahlgren et al., 2004; Delmelle et al., 2015). But as we have already mentioned in the first part, volcanic soils must be properly managed in order to maintain high productivity and prevent deterioration (Delmelle et al., 2015).

Napa and Sonoma valley

Moving to the North American side, wines from the Pacific coast are growing in popularity and quality. Among them, California’s vineyards are becoming more and more known worldwide, with the famous Napa and Sonoma valleys. In 1976, during the Paris Wine Tasting, both white (Chardonnay) and red (Cabernet Sauvignon) wines from the Napa Valley were judged in a blind test superior to the French wines, revolutionizing the wine world.

The complex geological history of the area is giving a mixture of deposits and landforms which have played a fundamental role in the success of those wines. The topography is also giving a wider range of climatic conditions and sun exposure that brings to a mixture of microenvironments and, therefore, to different cultivations (Swinchatt et al., 2018).

These valleys are constituted by marine and continental sediments, due to subduction activity, and Pliocene-Pleistocene volcanic rocks (Kunkel and Upson, 1960).

Among them, we can find the “Sonoma Volcanics” geological formation, composed of pyroclastic tuff, obsidian, pumice and andesite breccias. This formation is the parent material of many soils of these wine regions.

The two winning bottles of the Paris Wine Tasting of 1976. From cnn.com

For what concern the Napa Valley, for instance, we can find three different types of bedrocks which are playing an important role: the Great Valley sequence (sandstones and shales of volcanic origin, rich in quartz and felspar), the Franciscan Formation (rich in Calcium and Sodium feldspar) and the Napa volcanics (tuffs, lava flows, volcanic glass, pyroclastic and mudflow deposits). A key role to the complex topography and the rock types of the area is the San Andreas fault, affecting also vineyards and wineries.

The various mineralogy of the soils and the topography led to different types of grapes, with the hillsides vineyards (e.g. Mayacamas Mountains) producing smaller grapes, but with a higher concentration of colour and flavours, and grapes as the Pinot Noir preferring Calcium-rich soils (Boyd).

Due to the mixture of rock formations, alluvial fans are extremely important. As an example, at Rudd Oakville Estate in Napa, the southern part is constituted by a fan with portions of andesitic Sonoma volcanics, which was missing in the northern side, with the results of noticeable differences in the character of grapes and wines between the two areas (Swinchatt et al., 2018).

Canary Island

How can these volcanic islands, far 100 km from the African coast, in the Atlantic Ocean, produce wines known for centuries?

The production of wines in this area can be described as the absolute will of cultivation in an (at first look) harsh land, with steep black volcanic flanks and strong winds blowing along with the islands. But the combination of these two factors is probably the key for astonishing vineyards and unique wines, also cited by Shakespeare in five plays. In order to protect the grapes from the wind, the vineyards are planted in individual depressions and surrounded by semi-circular walls (Caplan, 2020).

The typical wall-vineyard in Lanzarote Island (Spain). Credit Gerald Haenel/Laif from foodandwine.com

Lanzarote Island is partly constituted by basalt, and given the low rates of precipitation, it weathers slowly. However, the secret of those flourishing vineyards is in the scoop where the grapes are placed, with manure applied around the roots (providing nitrogen and phosphorus) and a mulch of lapilli, several centimetres thick, which is preserving moisture. Lapilli gives the best surface to attract dewfall and have the right balance between high permeability and evaporation.

While in Lanzarote lapilli are the mulch, in Tenerife, they are substituted by pumice. On this island, another important component of the volcanic soil is the allophane, formed by the breakdown of volcanic glass, with the ability to retain water and humus (Maltman, 2018).

The main wines produced in the archipelag are red (Listán, Negro, Negramoll and Tintilla) and white (Malvasía, Listán bianco, Marmajuelo).

The list of volcanic areas and soils is endless (Chile, Greece, France, …); however, we hope you enjoyed this two-part tiny world-wine tour!

And once again…Cheers!!

References

Thomaidis, K., Troll, V. R., Deegan, F. M., Freda, C., Corsaro, R. A., Behncke, B., & Rafailidis, S. (2021). A message from the ‘underground forge of the gods’: history and current eruptions at Mt Etna. Geology Today, 37(4), 141-149.

Dahlgren, R. A., Saigusa, M., & Ugolini, F. C. (2004). The nature, properties and management of volcanic soils. Advances in agronomy, 82(3), 113-182.

Delmelle, P., Opfergelt, S., Cornelis, J., Ping, C., (2015). Volcanic Soil in The encyclopedia of volcanoes (Chapter 72). Elsevier.

Swinchatt, Jonathan P., David G. Howell, and Sarah L. MacDonald. The scale dependence of wine and Terroir: examples from coastal California and the Napa Valley (USA). Elements: An International Magazine of Mineralogy, Geochemistry, and Petrology 14, no. 3 (2018): 179-184.

Kunkel, Fred, and Joseph Edwin Upson (1960). Geology and ground water in Napa and Sonoma Valleys, Napa and Sonoma Counties, California. US Government Printing Office.

Boyd, Gerald. The Science behind the Napa Vally Appellation; An examination of the geology, soils, and climate that define Napa Valley as a premier grape growing region.

Caplan, N., (2020). https://www.foodandwine.com/travel/canary-islands-wineries

Maltman, A., (2018). Vineyards, rocks, and soils: The wine lover’s guide to geology. Oxford University Press.