August in Ladakh is a time of golden fields and harvest songs, not snowstorms. Yet in 2025, this rhythm broke. Panikhar village in Ladakh woke beneath fifteen centimetres of snow, an unseasonal blanket that changed the functioning of the valley and stunned its people. What began as a glaciological field trip turned into a firsthand encounter with climate uncertainty. This blog captures those extraordinary days when August brought winter to the Trans-Himalayas, revealing how mountain communities endure, adapt, and find resilience amid the unpredictable pulse of a warming world.

Firstly, the lights went out. Then the internet died. By morning, approximately fifteen centimetres of snow had buried the golden wheat fields of Panikhar village; such things simply don’t happen in Ladakh in August. “Snow in August?” Iliyas shook his head as we stood together in his transformed wheat field, his grandson Haider beside him, both staring at the white blanket that had swallowed their harvest overnight.” August has always meant cutting wheat, not digging it out.”

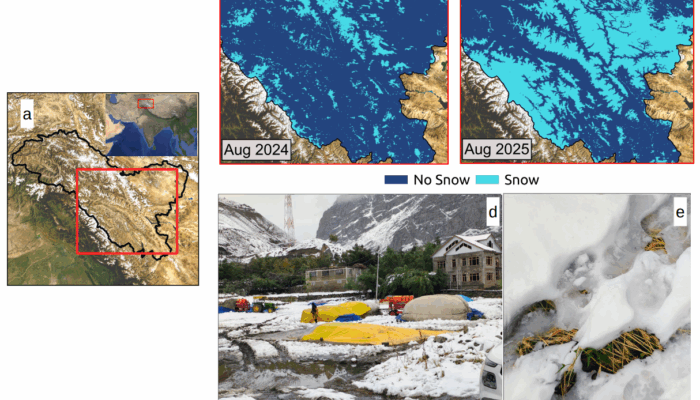

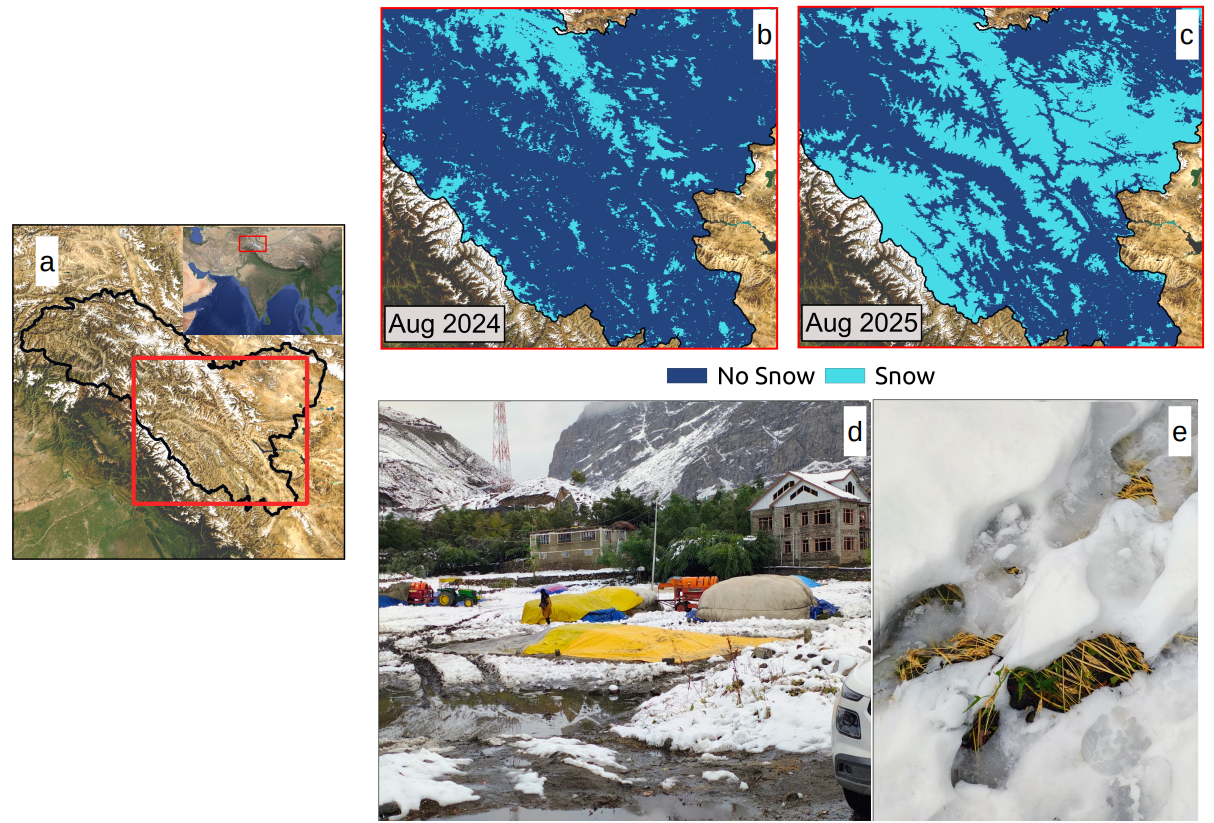

In the remote valleys of Ladakh, where ancient trade routes wind through some of the world’s highest inhabited landscapes, the rhythm of life has long been dictated by seasonal patterns. Where farmers were sharpening their sickles for harvest. Shepherds grazed their flocks in high mountain pastures, and haymakers collected fodder. Our team from IIT Roorkee participated in a glaciological field expedition in the Trans-Himalayas funded by Prof. Saurabh Vijay (Supervisor). However, on August 26, 2025, nature disrupted this carefully staged lifestyle with an unexpected arrival of snow (Figure 1).

A Valley Holds its Breath

For forty-eight hours, Panikhar existed in a state of suspension. Without electricity, families gathered around solar lanterns and battery-powered lights, if they were fortunate enough to have them. Others faced complete darkness as the sun set behind snow-laden peaks. We found ourselves sharing meals by battery lamp with our hosts, the conversation switching between concern for crops and amazement at the unprecedented event. The communication blackout added a surreal quality to the crisis. In an age where even the most remote mountain villages stay connected through mobile networks, the sudden silence felt like stepping back in time. We couldn’t call home or check the weather forecasts. The snowfall also exposed vulnerabilities in the region’s infrastructure systems. Road networks, already tenuous in this mountainous terrain, became temporarily blocked, cutting the transportation of fresh vegetables, fuels, medicines, foods, and other essential commodities that villagers depend on from outside.

Race Against Time

As precipitation stopped on the next day, the village had transformed into a hive of urgent activity. We watched Iliyas go and look for his sheep and goats. As we went into the village, we saw them working frantically to protect what they could of their crops. Plastic tarps appeared from storage rooms where they’d waited patiently for winter (Figure 2). Hands that had been preparing for harvest were now fighting to save grain from an enemy that wasn’t supposed to arrive for months. “If the snow had stayed for even a few more days, we would have lost everything,” explained one local farmer. The spectre of food insecurity loomed large in communities where agricultural self-sufficiency often means the difference between prosperity and hardship.

Figure 1: (a) Panikhar and neighbouring villages (Maitasuru and Kargi) buried under unexpected August Snow with surrounding peaks showing widespread distribution of the August 26, 2025, snowfall (Image Credit: Aditya Mishra, IITM). (b) Snow pit with approximately 10 cm depth with ground beneath. (c) A rockfall event observed during fieldwork was triggered by rapid snowmelt and freeze-thaw cycles following unseasonal precipitation. (d) Our team measures the snow observations with local resident Iliyas and his grandson, Haider. [Credit: All authors]

For the region’s pastoral communities, the unseasonal weather triggered immediate crisis management protocols. Shepherds, many of whom had driven their flocks to high summer green fields just months earlier, found themselves racing against time to bring their animals to safety (Figure 3). We also observed some dead sheep and goat cadavers that may have died due to hunger. The Bakarwal community, known for its seasonal migrations, also faced particular difficulties. Their route through the Parkachik-Bot Kol Pass, which connects Ladakh to Kishtwar, was temporarily blocked.

Figure 2: (a) Regional map showing the Ladakh region (red box). (b–c) Satellite-derived snow/no-snow classification for August 2024 and August 2025 using the MODIS snow cover product (MOD10A1), highlighting a substantial snow cover in 2025. (d) Villagers’ emergency response involves harvesting wheat and covering it with tarps to protect the grain from snow damage in Panikhar village. (e) Close-up view of unharvested wheat stalks submerged under snow cover, illustrating the threat to standing crops during the critical August harvesting period. [Credit: Aditya Mishra and all authors]

The Science Behind the Snow

When we finally managed to measure the snow properly, despite not having brought a snow density measuring instrument, we measured a snow depth of 10 cm with a density of 0.365 g/cm³ (Figure 1d). Spread across several square kilometres, this represented a significant water pulse that melted within 2 days in lower areas and longer at higher elevations under the intense late-August sun.

This rapid melt can trigger cascading effects, including saturated soils, increased stream discharge, and frequent rockfall risks. We documented several rockfall events during our stay in the village (Figure 1c). The concentrated water release, essentially compressing days of typical precipitation into a brief period, creates localised hazards affecting both villagers and travellers. One morning, we were heading to our research site when we spotted a group of trekkers from Delhi in the distance. Suddenly, a deep rumble echoed through the valley. Iliyas’s voice cut through the air—sharp, urgent: ‘Rocks coming down! Run!’—followed by his piercing whistle that sent everyone scrambling for cover. Fortunately, everyone was safe. For mountain communities, such hazards are part of life—but the timing and frequency had everyone on edge.

Figure 3: (a) Shepherds driving sheep herds down from high-altitude fields against a backdrop of snow-covered peaks. (b) Mixed livestock, including cattle and goats, are being moved to lower grasslands following the August 26, 2025, snowfall event that forced early descent from summer grazing areas. [Credit: All authors]

Beyond the Valley

As our communication was restored, we learned that Panikhar’s experience wasn’t isolated. Leh district experienced its highest August rainfall since 1973, with 47 millimetres recorded on August 25, just one day before the Panikhar snowfall [1]. Earlier in the year, unseasonal weather events devastated apricot orchards in the Kargil district, causing widespread crop damage and economic losses that rippled through local communities [2]. The snowfall brought Ladakh’s tourism sector to an immediate halt. Trekkers heading toward the Parkachik-Bot Kol Pass found themselves stranded, while local guides, porters, homestays, and tea stalls lost crucial peak-season income. Authorities suspended all movement through this pass and all nearby trek routes, their caution intensified by a recent incident where 40 mountaineers became trapped during a blizzard on the nearby Nun Kun Trek (7,135m) [3].

Climate scientists had long predicted such erratic weather patterns in high-altitude regions, but witnessing the lived reality felt different from reading research papers. We were documenting not just a weather event, but a glimpse into a future where mountain communities must navigate increasing uncertainty with traditional knowledge systems designed for predictable patterns.

As climate variability continues to increase across the Himalayas, the experiences of communities like Panikhar become increasingly valuable for understanding how mountain societies navigate uncertainty. Their stories remind us that behind every climate statistic lies a human reality: families gathered around solar lights, shepherds racing to save their flocks, and farmers watching snow cover their ready harvest. These are the faces of climate adaptation in some of the world’s most challenging environments, where resilience isn’t just an academic concept but a daily necessity for survival. Memory of the vulnerabilities of those hours will hopefully influence community preparedness strategies for years to come. In the mountains, every weather event brings a new challenge. Documenting events like Panikhar’s snowfall is vital, not only for climate science but also for shaping the adaptation strategies that match the reality of mountain people.

Lessons from the Event

Three days after the snow began, life in Panikhar had returned to its rhythms. Mobile towers reconnected the valley to the world. Solar panels, cleared of snow, powered lights and phones again. Most remarkably, the farmers had saved their harvest. The shepherds had brought their flocks safely down from the high pastures. The village had adapted, survived, and was already beginning to incorporate the experience into its collective wisdom. The 2025 snowfall demonstrated how a single weather event can simultaneously disrupt agriculture, pastoralism, tourism, infrastructure, and migration patterns, with impacts cascading rapidly through interconnected social, economic, and ecological networks.

As we packed our research equipment and prepared to leave, I couldn’t stop thinking about a conversation we’d had with a shepherd while installing instruments in a remote area. ‘Is there any way to know these events earlier?’ he had asked, his weathered face etched with concern. ‘So we don’t get stuck up here without food for so long when the weather turns?'”. We didn’t have an answer. But we had witnessed something profound: how communities at the frontlines of climate change adapt not just to new weather patterns, but to the loss of predictability itself. The snow that fell on Panikhar in late August has long since melted. Streams have returned to their normal flows. Mobile towers once again connect the valley to the wider world. In the mountains, every weather event is both a challenge and a teacher. The lesson from this one was clear: resilience in an era of climate change means preparing not just for known extremes, but for surprises that rewrite the calendar itself.

As we drove away from Panikhar, our vehicle winding down roads now clear of snow but still marked by rockfall debris, we carried with us more than scientific data. We had witnessed the human face of climate adaptation: families gathered around solar lights, shepherds rushed to save their flocks, and farmers watched as snow covered their ready harvest. These are the real stories behind climate statistics: communities that have spent generations reading the mountains now learning to read a future they never expected to see.

Edited by Emma Pearce

Further Reading

To learn more about the science acquired from this fieldwork, have a read of the authors scientific articles

- Quantifying short-term backwasting rates of a supraglacial ice cliff at Machoi Glacier in the Indian Himalaya.

- Mapping Glacierized Regions With Quad-Pol Dual Frequency LS-ASAR: Insights for the NISAR Mission.

- High-Frequency observation of glacier ice velocities at Drang Drung Glacier, western Himalaya, using a terrestrial time-lapse imaging system.