Arctic fieldwork is a meticulous dance with the ever-fickle weather, where nature’s temperament can determine the course of scientific endeavors. Rain or fog can swiftly put a halt to even the most well-laid plans. This holds true for Greenland, where proximity to the ice cap doesn’t shield researchers from the capriciousness of the climate. In August 2023, the Deep Purple ERC Project embarked on a two-week long mission to the remote 79°N in Qaanaaq, Greenland. Our mission: to unravel the mysteries of the darkening ice.

Colored ice

The Greenland Ice Sheet, under assault from accelerating melting rates, bears witness to an unlikely culprit – minuscule ice and snow algae. While invisible to the naked eye, these microorganisms wield a profound influence. Their growth on the glacier’s surface amplifies heat absorption, which, coupled with their purple, red, or green hues, diminishes the ice’s reflective albedo. The consequence is a hastening of environmental melt. Astonishingly, approximately 40% of Greenland’s annual mass loss is attributed to this biological darkening phenomenon (Chevrollier, et al. 2022). Yet, the question of why these organisms have chosen this harsh, resource-scarce, and weather-beaten terrain as their home remains unanswered.

The difficulty of planning in the Arctic

In the Arctic, weather conditions shift with the caprice of a child’s mood, rendering forecasts dubious beyond a mere 24-hour window. Cumulonimbus storm clouds can metamorphose into benign cumulus clouds within a matter of hours. The Arctic Circle’s erratic weather patterns, wrought by volatile currents, usher in daily fluctuations between warm and cold fronts. Planning a helicopter expedition to the remote snow line of the Greenland Ice Sheet thus becomes as much an art as a science. Our strategy hinges on a simple ritual: gazing out the window. If the sky is gray, our plans remain grounded; otherwise, hope endures.

The final day

The preceding three days had been characterized by persistent rain and overcast skies, which had effectively tethered our team to the ground. As we awoke on this particular morning, it seemed like déjà vu as we peered out the window, greeted once more by the familiar sight of rain and gray skies. As we settled into our daily routine, tending to apartment chores and monitoring our samples, the phone call from Air Greenland shattered our reverie. The caller hinted at a lifting cloud ceiling and a possible four-hour weather window. The catch? Uncertainty veiled the exact conditions on the Greenland Ice Sheet, leaving us with a daunting choice: seize the opportunity and risk helicopter inability to land on the ice or conserve time, money, and energy while avoiding the impending disappointment. After deliberation, we chose the former, donning our outdoor gear with haste.

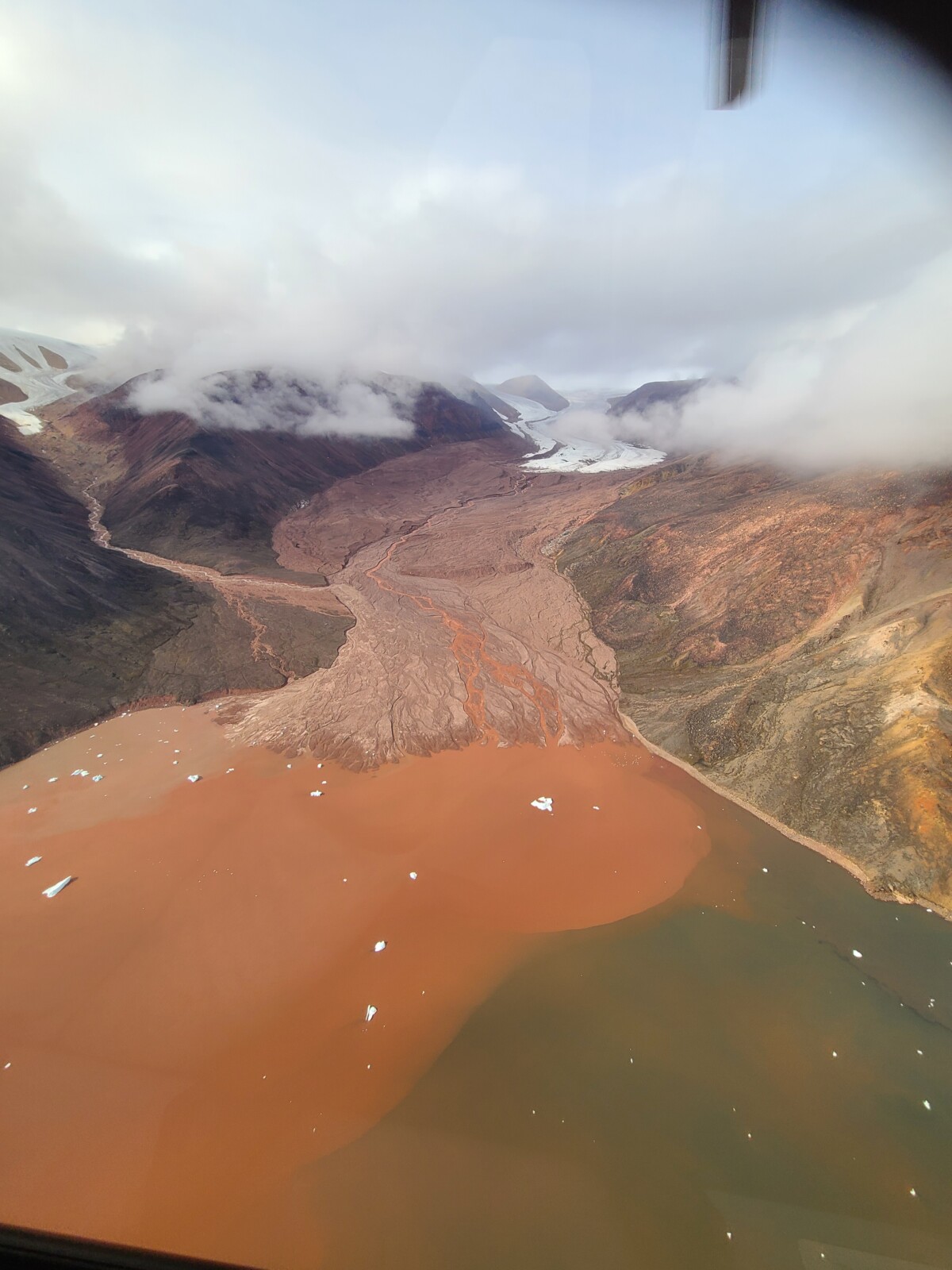

With equipment and backpacks in hand, we called for a ride to the airport, arriving just 30 minutes after giving the trip the green light. Anticipation gripped us as we awaited the helicopter, eyes glued to the airport windows. Spying the aircraft across the fjord, smiles spread across our faces. The window of opportunity was widening. Airport staff assisted in loading our gear, and off we went. The helicopter afforded us an awe-inspiring vista of Earth’s geological and glaciological wonders. Glaciers snaked through mountains, depositing sediment plumes into fjords (Fig. 1). Crevasses appeared minute and harmless from our aerial perch, and the deep blue pools of water beckoned. Only a few arctic birds dared to inhabit the desolate, skinny sedimentary mountains. From our vantage point, we spotted another inhabitant: purple algae. This vibrant ice algae blanketed the ice sheet, as if draping it in purple velvet (Fig. 2). After a 20-minute flight, the helicopter touched down, and we eagerly explored our new sampling terrain. We navigated ice humps, leaped over glacier meltwater streams, and scoured areas for sample collection.

Figure 1: Sedimentary plumes flow out of the glacier and into the fjord. The color is from different minerals, mainly iron. [Credit: Katie Sipes]

The moment I had anticipated arrived, and I took a pause to absorb the profound solitude of this untouched realm, a place where no human had ever ventured, and likely, no one ever would again (Fig. 2). As far as the eye could see, there was no sign of life. It was a testament to the tenacity of these microscopic organisms, surviving in such a remote location without a visible source of carbon or micronutrients. While appreciating the stark beauty of this environment, I noticed the encroaching fog, a signal that our weather window was indeed closing. Soon, the helicopter pilot sounded the 15-minute warning, prompting us to swiftly pack our gear.

Figure 2: On the ice sheet, the topology is carved with purple ice algae. Persons pictured: Alex Anesio, Christoph Keuschnig [Credits: Katie Sipes]

Back home

We departed from the ice sheet with over 20 liters of ice, water, and glacial ice cores, ready for analysis, our faces beaming with satisfaction. Joy radiated throughout the helicopter during our return flight (Fig. 3), and it felt as though a movie soundtrack played in the background. Throughout the journey back to Qaanaaq, we remained glued to the helicopter windows, soaking in the breathtaking terrain and expressing our gratitude to the universe for granting us the privilege of studying its grandeur.

Figure 3: The postdoc side of the team on the helicopter ride home; starting left, Christoph Keuschnig, Thomas Turpin-Jelfs, Beatriz Gill-Olivas and Katie Sipes (author). [Credits: Katie Sipes]

Further reading

- Read more about the Deep Purple – Darkening of the Greenland Ice Sheet Project on the project’s webpage and blog

- Check out this other blog post by Deep Purple PhD student Elisa Peters to get more insights into the project

- Check out a similar story about “Hunting snow algae from the Alps”

- Deep Purple’s fieldwork adventures were recently highlighted in our Fieldwork Stories

Edited by Loeka Jongejans and Lina Madaj

Katie Sipes is an American bioinformatician and environmental microbiologist who has been part of the Deep Purple ERC project at Aarhus University since 2022. Her work involves employing bioinformatics to investigate the microbiological dynamics and ecology of the Greenland Ice Sheet. During her leisure time, she enjoys teaching her cat to use communication buttons and indulges in riding her 2008 Honda CBR600RR motorcycle. She tweets as @KatieSipes42. Contact email: ksipes@envs.au.dk