In Chile, gender imbalance in science mirrors the international context, even though the Americas have been recognised as a region where women’s representation in science has increased, compared to other countries (UNESCO 2015 statistics and this study). However, Chile still has one of the lowest ratios of women participating in STEM (33.1%), followed by Mexico and Peru, as shown in this study. In the last “Women of Cryo” blog, we looked at how these statistics are represented at a local scale in Chile. In this second part of the blog, we will share the stories of women tackling these gender imbalances in the cryosphere and working on the Andean glaciers of Chile.

Introduction to the stories of women working on Chilean glaciers

During the last two decades, women, who had historically been marginalised from participating in STEM and in particular glacier science (see this study), have been increasingly present in glaciological research in Chile. To provide context about the circumstances and conditions that inhibit women and their transition into the field of glaciology in Chile, we share the following stories of three women in Chile, their diverse roles in the cryosphere, and how they are connected with the Andean glaciers.

Shelley MacDonell, a glacier scientist dedicated to the study of Andean glaciers: from the Penitentes to the Antarctic Peninsula!

Dr. Shelley MacDonell is a glaciologist from New Zealand. She holds a B.Sc. in Geography (2004), a Ph.D. in Geography (2009) from the University of Otago and came to Chile in 2009 for a postdoc at the Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Áridas, CEAZA (Center for Advanced Studies in Arid Zones). She currently leads the Glaciology Lab at CEAZA, which is focused on a myriad of glaciological topics in the Coquimbo region as well as in the Antarctic Peninsula. She focusses on the understanding of climate and glacier interaction, geophysical studies on rock glaciers, hydrology, and climate change in the Andean semi-arid zone. Shelley’s story has been translated from the original article, found here.

Her parents had always strongly encouraged Shelley and her sister to follow their passion, so much so that they became the first in their family to complete their secondary education. Her father stimulated her scientific curiosity when she was a little girl with observations and experiments in situations of daily life. This observational and analytical approach to nature eventually led her to become a field scientist. A defining moment occurred when she was 12 years old, when her dad took her to the International Antarctic Center in Christchurch. That visit made her wish to go to Antarctica and brought Shelley closer to glaciers in her college years.

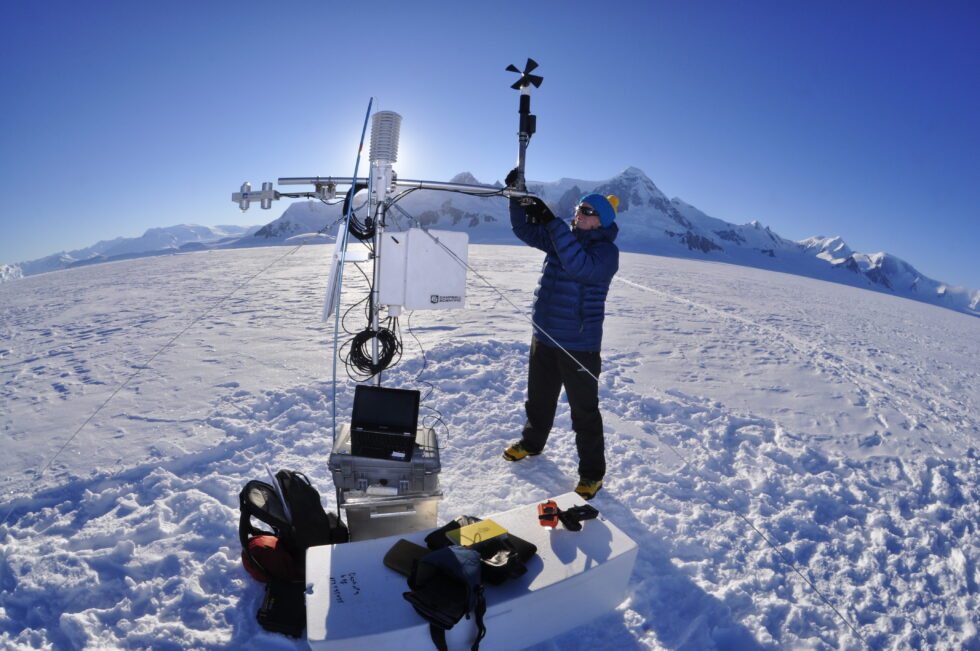

Shelley working on an Automatic Weather Station (AWS) on the Müeller Ice Shelf, Antarctic Peninsula during fieldwork. Photo Credit: Shelley MacDonell, Francisco Fernandoy

Shelley was the only woman in the Glaciology Lab at CEAZA between 2009 and 2017.

“The day I hired two female scientists; I noticed the change in the team. Having people with different experiences, mindsets and skills enriches the results of the work we do and provides innovative solutions to old and new problems. Really, I do not want to return to a situation without this diversity of views and I recognize that we can still diversify more.”

Shelley has been continuously advocating for women’s participation in glaciological research in Chile and the importance of promoting this field to young girls and women. She and her team make a point to incorporate female interns into the group. Shelley is planning to carry out a Chilean branch of the Inspiring Girls Expeditions, a program firstly established by the American glaciologist Erin Pettit seeking to promote the participation and diversity of women in field sciences and outdoor recreation.

Shelley working on Tapado glacier (Coquimbo region, Chile) and she is standing among the most famous ice-features of the dry and high Andean mountains, the Penitentes. Photo credit: Shelley MacDonell, Conicyt.

On a final note, Shelley shares with us an important thought about being a female scientist:

“I think the path to becoming a scientist is long. In addition, society is often not flexible enough in the face of all the roles that are imposed on women and those that women have naturally. Due to this, there are prejudices related to the level of commitment that we can acquire in our careers. For example, I have been in graduate programs interviews, where female applicants have been asked if they expect to get pregnant in the coming years or how they are going to balance the tasks that are required at home, versus the work that the study program imposes. For me, this is not only impertinent but can also be a disincentive for a woman to continue a path in science. We will not have progress in the way of seeing the contribution that we can make as women to society until these types of attitudes are changed.”

Francisca Bown, a pioneer female glacier scientist in Chile

Francisca Bown is one of the first Chilean female glaciologist “made in Chile”. She holds a B.Sc. in Geography (1997) and a M.Sc. in Geography (2004) from the University of Chile, and an M.Sc. in Oceanography (2015) from the University of Concepción. For her, the path to glaciology was not drawn from a childhood dream, but instead showed up just at the end of her undergraduate studies. At that time, glaciology in Chile consisted of only a few “pioneer glaciologists” in her words. By the end of 1990’s, these people paved the way for younger and upcoming generations of Chilean glaciologists.

Francisca Bown enjoying the outdoors, practising yoga and writing ‘geostories’ . She also co-funded Tambo Austral geoscience consultants in Valdivia. Photo Credit: Francisca Bown.

In the early 2000s, Francisca completed her B.Sc. at the University of Chile, which, together with the University of Magallanes, was a pioneering public institution undertaking research in glaciology in Chile. Francisca affirms that she was lucky because she was in the right place at the right time to learn glaciology when there were only a few people around who could teach her about this science. When she entered this field, she thought:

“Hey, this thing about studying glaciers is absolutely fantastic (…) It is a new whole world, how didn’t I think about this before?”.

When she started, glaciological research was dominated by men in Chile. However, as the field grew, this imbalance gradually changed (although there is still a gap that needs to be addressed). In either case, Francisca remembers a few women she worked with during her early stages in glaciology when she was a research assistant at the Glaciology and Climate Change Lab at the Centro de Estudios Científicos (CECs), Chile. Gradually, other women made their way into this field, including Anja Wendt, (PhD Geodesy), Guisella Gacitúa (PhD Radio-glaciology), Paulina López (PhD Water Sciences) and Daniela Carrión (BSc Geography).

Francisca Bown working with a DGPS station in Antarctica. Photo credit: Francisca Bown.

An unexpected and kind gesture from a well-known glaciologist and Professor of Meteorology at Utrecht University, Johannes Oerlemans, motivated Francisca during her early years in glaciology. At that time, she was studying ice-flow models proposed in papers by Oerlemans (paper 1, paper 2). She herself recalls:

“And with all the youthful naivety that I had, maybe unaware of his (Oerlemans) academic status, I wrote an email introducing myself and respectfully asking him to teach and explain to me a few questions regarding some parts of his models that I didn’t understand. To my surprise, he responded to my email, and I felt that he empathised with me, this young female student from a remote country called Chile that was learning about Chilean glaciers. I guess that he was used to receiving enquiries and requests from students that were more familiar with glaciology, and those students came from such regions as Europe, North America and Russia”.

In their exchange, Oerlemans also told her about the Karthaus Summer School on Ice Sheets and Glaciers in the Climate System held in Northern Italy every year since 1995 which Francisca excitedly applied for. A while after their email exchange, Francisca unexpectedly received a copy of the recently published “Glaciers and Climate Change” book, a present that she still treasures to this day. Francisca was accepted to be part of the 2002 version of Karthaus, the only Latin American female student to participate that year.

Although originally drawn to physical geography, with time, Francisca’s interest turned to questions related to gender diversity, and ultimately lead to her current participation in a recently established International Glaciological Society’s (IGS) Diversity and Inclusion Committee. There, she represents Latin America, whose participation has been historically low in comparison to other continents (e.g. North America and Europe).

Natalia Morata, an ice cave explorer on the remote fjords of the Southern Patagonian icefield

Natalia Morata is a caver, speleologist (the scientific study of caves), translator, and interpreter born in Barcelona, Spain. She is currently the vice president of Centre Terre, a French association founded in 1992, bringing together cavers and scientists, eager to pool their skills to carry out explorations. Natalia has been working on the coordination and the logistics of several expeditions to insular areas close to the Patagonian fjords in 2014, 2017, and 2019. Her career path to where she is now has been astonishingly eclectic. Natalia’s story has been translated from the original article, found here.

It all began when Natalia started practicing caving in her teens:

“The desire to practice caving came to me almost out of curiosity. In my house, my parents tried to dissuade me with phrases such as «that’s not for girls, it’s very dangerous, etc». One day I saw a brochure from the caving section in my mountain club announcing an introductory course. I had just turned 18, so I signed up… And here I am!”.

Natalia exploring and surveying a limestone cave in the Madre de Dios archipelago, Southern Patagonia. Photo credit: Centre Terre.

Although Natalia focused on becoming a translator and interpreter in Switzerland during her undergraduate years, her caving spirit never faded. She spent many years reading about Centre Terre’s work in Patagonia and dreamed of being part of something like this, but it never crossed her mind to contact them. It was only after arriving in Chile in 2009 that Natalia decided to contact Centre Terre, just after they had announced that 2010 would be their last expedition to Patagonia.

“Luckily, they changed their mind!”.

Natalia’s first expedition with the Centre Terre was to Diego de Almagro Island in 2014, a limestone and marble land located in the Kawésqar National Park where she spent nearly 2 months living with the rest of the expedition crew among scientists, speleologists, and explorers. From the beginning, one of the things that drew Natalia’s attention to the work that Centre Terre was carrying out, was their efforts in public outreach during each expedition. The information and discoveries collected by the association led e.g. to the recognition of the Madre de Dios archipelago as a Protected National Asset in Chile as of 2007.

Regarding the promotion of initiatives that help to encourage the participation of girls and young women in the field of glaciology or related fields, Natalia notes that Centre Terre must support women to overcome barriers that discrimination has built because of sex, gender, religion, to name a few.

Natalia explaining some of the activities for the project “Cuerdas y Más” at the Miguel Montecinos School in Puerto Edén, 2019. Photo credit: Centre Terre.

Natalia was inspired to start a project called “Cuerdas y Más”, the first children’s expedition to the Témpanos glacier in the Southern Patagonian Icefield. The goal is to share the geographical and speleological knowledge collected from the Centre Terre expeditions on the karstic and glacial caves of the Patagonian channels to local communities living near glacial environments.

“The only thing I can think of to say to my future female expedition members is to go out and explore and experience it for themselves, they do not depend on their parents, brothers, cousins, or boyfriends to do that. If they are motivated, they have everything they need to learn and become self-reliant in any setting.”

Edited by Emma Pearce, Maria Scheel and Marie Cavitte

Further reading

You can find Dr Shelley MacDonell’s and Natalia Morata’s original interviews here:

- Fundación Glaciares Chilenos. (2021, February 11). Día Internacional de las Mujeres y Niñas en la Ciencia: Entrevista a la Dra. Shelley MacDonell

- Fundación Glaciares Chilenos. (2021, February 11). Día Internacional de las Mujeres y Niñas en la Ciencia: Entrevista a la Espeleóloga Natalia Morata

Other references found in this blog post:

- UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2015).

- Espinoza, C. (2019). Mujeres en ingeniería y ciencias: un tercio productivo y diferenciador. Beauchef Magazine-Especial Mujeres

- Rushing, J. (2014). Women and Glaciers: Changing dynamics in sport, science and climate change. [Bachelors’s Thesis, University of Oregon]. DSpace Repository

- Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Áridas, CEAZA (Center for Advanced Studies in Arid Zones in English)

- Laboratorio de Glaciología, Grupo de Geociencias del CEAZA (Glaciology Lab)

- Inspiring Girls Expeditions

- Lorenzo y Valentín, Los Niños de la Patagonia. Geosciences Tales

- Centro de Estudios Científicos de Valdivia

- Van de Wal, R., & Oerlemans, J. (1995). Response of valley glaciers to climate change and kinematic waves: A study with a numerical ice-flow model. Journal of Glaciology, 41(137), 142-152

- Oerlemans, J., Anderson, B., Hubbard, A., Huybrechts, P., Johannesson, T., Knap, W. H., Schmeits, M., Stroeven, A. P., van de Wal, R. S. W., Wallinga, J. and Zuo, Z. (1998): Modelling the response of glaciers to climate warming, Climate Dynamics, 14, pp. 267-274

- Karthaus Summer School on Ice Sheets and Glaciers in the Climate System

- Oerlemans, J. (2001). Glaciers and climate change. Routledge. 1st Edition

- 2002 list of students of the Karthaus Ice Sheets and Glaciers in the Climate System Summer School

- “Cuerdas y Más” Project. The first children speleological expedition to the Southern Patagonian Icefield

Paola Araya holds a B.Sc. in Geography from the Catholic University of Chile and is a MSc Student in Meteorology and Climatology at the Geophysics Department of the University of Chile where she focused on modelling projections of glacier change along the 21st Century for the Maipo River Basin, central Chile, located to the east of the Chilean capital city, Santiago, providing most of its drinking water. Paola tweets as @martianglaciers and can also be contacted at pparaya@uc.cl.

Paola Araya holds a B.Sc. in Geography from the Catholic University of Chile and is a MSc Student in Meteorology and Climatology at the Geophysics Department of the University of Chile where she focused on modelling projections of glacier change along the 21st Century for the Maipo River Basin, central Chile, located to the east of the Chilean capital city, Santiago, providing most of its drinking water. Paola tweets as @martianglaciers and can also be contacted at pparaya@uc.cl.

Helena Valenzuela-Astudillo holds a B.Sc. in Geography from the University of Chile. Her undergraduate research focused on the study and geomorphic characterization of rock glaciers at the Yerba Loca Sanctuary, an important basin near Santiago. Helena tweets as @helenas_va and can also be contacted at helena.vastudillo@gmail.com.

Helena Valenzuela-Astudillo holds a B.Sc. in Geography from the University of Chile. Her undergraduate research focused on the study and geomorphic characterization of rock glaciers at the Yerba Loca Sanctuary, an important basin near Santiago. Helena tweets as @helenas_va and can also be contacted at helena.vastudillo@gmail.com.

Paola and Helena collaborate as a volunteering members of the NGO Fundación Glaciares Chilenos where they together and other people are working on the project “Entre Mujeres y Glaciares” (pages 20-21) (“Between Women and Glaciers” in English) related to multiple initiatives promoting women’s contribution to cryospheric sciences from STEM, art, literature, sports and activism. They tweet as @martianglaciers and @helenas_va, and can also be contacted through their respective emails, pparaya@uc.cl and helena.vastudillo@gmail.com.

NGO Fundación Glaciares Chilenos is a non-profit organization that works for the protection of glaciers located in Chile. Our mission is to educate and communicate about glaciers in our national territory. By articulating collaboration with different sectors within society such as academia, civil society, and local settlements that depend on glaciers, either economically or as a vital resource for human development, we pursue raising awareness about the importance of glaciers in the context of environmental stewardship and protection. In order to address the complex issue of glacier protection, NGO Fundación Glaciares Chilenos focuses on three main activities: educating the Chilean population about glaciers, making the topic more visible, and providing accurate and comprehensible information about glaciers through effective science communication. We are always welcoming new members into our organization, come on and join us!