Last summer we got the chance to participate in an incredible Arctic expedition. The mission was clear and yet unclear at the same time: Bring your fanciest laser technology on a wooden schooner. Then cross the Atlantic and sail to the fjords of southern Green

land and conduct science throughout the journey. During most of our expedition, our “scientific lab” contained icebergs, glaciers and beautiful fjords or open waters; And we even got the chance to experience northern lights and a visit from a polar bear. But unavoidably also the not so pleasant feeling of seasickness….

The expedition:

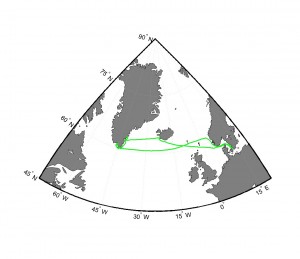

On June 24rd 2014 a majestic wooden schooner, set sail and began a fantastic journey across the North Atlantic Ocean. The journey was split up into three legs: 1) from Copenhagen (Denmark) to Reykjavik (Iceland), 2) from Reykjavik to Narsarsuaq (Southern Greenland), 3) from Narsarsuaq to Copenhagen. The first and the third leg of the journey was primarily “transporting” the ship to the remote environment where most of the scientific research projects was scheduled. On two of these legs, we were the only scientists onboard experiencing the amazing feeling of being on an old wooden schooner crossing the North Atlantic Ocean. The second leg of the journey was the part with the most scientific enrolment. On this leg, scientists with different backgrounds and interests were onboard conducting experiments primarily in the remote fjords in the south-eastern part of Greenland.

Some people might recognize the ship as the ship used in the documentary “Expedition to the end of the world” where scientists and artists went on a polar expedition together. No artist participated this time and the aim of this expedition was purely scientific. The purpose was twofold; to conduct science in the Greenlandic fjords, second to gain experience before the realization of a future circumpolar scientific expedition.

The route of the trip, plotted using linear interpolation of the measured GPS positions. (Credit M. Winther)

The vessel was working as a floating field station and we were part of a larger team of scientists from different fields all taking advantage of this unique opportunity. Using the ship as a base for research had some logistical advantages, as it was easy to move from one location to another and research could be done onboard the ship or on land. On a typical day, some scientists would stay on the ship and others would jump into small zodiacs or use special airborne transportation. Then they would transport themselves to nearby field sites to collect data.

The expedition ended with a beautiful and fairytale-like morning on the 20th of September 2014. Sailing on a calm sea during an early summer dusk, with the first sunshine of the day in our backs, passing the old Kronborg castle (the Northern tip of Sealand, Denmark) and sailing with the sails the last miles back to the harbor across from the Queens palace in the center of Copenhagen.

Left: The view of Kronborg as seen from the Captains view. (Credit M. Winther). Right: Sun rise as sailing in the North-sea. (Credit M. Winther)

History of Activ

The research vessel used for this incredible expedition was the old ice-class cargo vessel named “Activ”. Activ was built in 1951, and was in the first 27 years used as a cargo vessel for the Royal Greenland Trading Company sailing on the eastern coast of Greenland. In 1978, the ship was re-rigged as a topgallant schooner with room for 16 persons including a Captain and crew members. Even after this update Activ remained as an “old fashioned” sail and motor-driven vessel, which means that it is preferable to sail only with sails, which need to be handled with pure manpower. With a total of 13 sails, everyone onboard was obligated to help when needed.

The Science

But now, let’s talk science. During this arctic shipboard expedition we brought a water vapor Cavity Ring down Spectroscopy (CRDS) isotope analyzer namely the Picarro G2301 analyzer. Using this analyzer we endeavored to perform online continuous measurements of the water vapor isotopes in the lower 25 meter of the marine boundary layer over the entire expedition. In order to measure the water vapor continuously, we made an onboard dual-inlet setup. For the majority of the expedition we measured from an inlet placed at the top (at approximately 25 meters) of the mizzen mast (stern mast). From this inlet the water vapor was drawn down to the instrument using a pump standing next to the Picarro analyzer. To prevent condensation of water vapor between the inlet and the analyzer, the water vapor was transported through an insulated heated (30°C) cobber stainless steel tube. The second inlet was at the end of an “arm” attached to the site of the vessel. This arm had the same kind of insulated heated cobber stainless steel tube for transporting the vapor in. The special thing about the arm is that it gives us the means to draw vapor from different elevations quickly and very easily and quickly.

Using this dual-inlet system we measured almost continuously, from 25meters above sea-level, for the full expedition time over both the ocean and in the fjords. When in the fjords and when we experienced calm weather, we used the “arm” to draw vapor from different heights above the water.

Left: The mizzen mast with the top inlet just above the navigation systems. Center: The “arm” with the second inlet attached. Right: Installation/reparation of the top inlet required harness ect. (Credit A.-K. Faber and M. Winther)

The purpose of our part of the expedition was to gain more knowledge about the physical processes affecting the water vapor in the atmosphere. This is important because we can use this knowledge to improve the general interpretation of the climate system, the representation of water vapor in climate models, and interpretation of observations on water isotopes in the Greenland ice cores.

The development of laser-based isotope analyzers are relatively new. Therefore only a very limited amount of vapor measurements exist for the Arctic region. Understandably we found that the unique route of the expedition yielded excellent conditions for monitoring the water isotopes in the vapor throughout the duration of the expedition.

Memorable moments:

Being on an expedition like this gave us a lot of unforgettable moments, of which only a few is written here.

The instrument we used for this expedition (the Picarro G2301 analyzer) was, together with the rest of the measuring and calibration setup, placed in the same cabin as we were sleeping. This was because of the limited space and the need for a stable “lab”. The cabins onboard were all with 2-3 beds and closets/chests for clothing etc. and therefore relatively large compared to our expectations. Though having a continuously running Picarro analyzer and setup in the closet, the cabin quickly became unwanted by anyone but us (since we had to stay there because of the limited beds onboard). Having the analyzer in the cabin, resulted in both some positive and negative consequences. For example, we never felt cold while sleeping in the cabin and there were more onboard privacy for us (sleeping in the lab-cabin). The downside was that we had to sleep with earplugs, since a constant noise at approximately 90 decibel from the instrument is not pleasant, and we had no closet for our clothes. But despite this we enjoyed being onboard, and we have had a lot of fun of our new meaning of “sleeping with Picarro”.

Being on a shipboard expedition in the south-eastern part of Greenland, comes with some expectations for spectacular adventures. On this expedition we were not disappointed, since we had a close encounter with a polar bear and multiple nights with the magic of Northern lights. The polar bear encounter was luckily not a threat, it just wanted some chocolate from the zodiac which was on the side of the vessel in the water. The bear was curious but nothing dangerous ever happened.

We both think that we have had an amazing expedition which have given us memories for life. Life as a young scientist in the arctic is not bad at all!!

Left: Iceberg watch from the side of the vessel when entering the fjords. Right: The vessel as seen from the top of the fore mast. (Credit A.-K. Faber)

Anne-Katrine Faber and Malte Winther are Ph.D. students at Centre for Ice and Climate, The Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. They are working with water isotopes and continuous measurements of N2O isotopomers, respectively.

Pingback: GeoLog | Looking back at the EGU Blogs in 2015: welcoming new additions

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week — slush on top of sea ice