Both the uncertainty inherent in scientific data, and the background and ethics of the communicators who report such data to any given audience, can sow doubt about the science of climate change. The perception of this duality is engrained in how the human mind works, whereby we tolerate lies but are always ready to condemn hypocrisy. We illustrate this through a personal experience that is connected to global environmentalism whilst providing some guidelines in communicating the science of climate disruption by humans.

In January 2017, the Spanish environmental magazine Quercus invited us to give a talk, at the Cabinet of Natural History in Madrid, about our article on the effects of climate change on the feeding ecology of polar bears. This made it to Quercus’ cover in February 2017 (1; see blog post here). During questions and discussions with the audience (comprising both scientists and non-scientists), we displayed a graph illustrating combinations of seven sources of energy (coal, water, gas, nuclear, biomass, sun and wind) necessary to meet human society’s global energy needs according to Barry Brook & Corey Bradshaw (2). This paper supports the idea that nuclear energy, and to a lesser extent wind energy, offer the best cost-benefit ratios for the conservation of biodiversity after accounting for factors intimately related to energy production, such as land use, waste and climate change.

While discussing this scientific result, one member of the audience made the blunt statement that it was unsurprising that a couple of Australian researchers (Brook & Bradshaw) supported nuclear energy since Australia hosts the largest uranium reservoirs worldwide (~1/3 of the total). The collective, environment-friendly membership of Quercus and the Cabinet of Natural History is not guilty of a lack of awareness of environmental problems, but they can of course challenge a piece of information backing the use of nuclear energy through his/her own and legitimate perspective. Having said that, the member of the audience was clearly not gauging the scientific evidence for which source of energy benefits biodiversity the most; instead, he was arguing for bias by the scientists who analysed the data relating biodiversity with energy production.

The stigma of hypocrisy

Indeed, when we humans receive and assimilate a piece of information, our (often not self-aware) approach can range from focusing on the data being presented to questioning potential hidden agendas by the informer. However, the latter can lead to a psychological trap whereby people might criticize a message if the messenger fails to practice what he/she preaches (3) — see simple-language summary of that assessment in The New York Times.

To put such a trap to the test, Jillian Jordan and collaborators (3) asked a total of 451 respondents to rank their opinion about four consecutive vignettes tracking the conversation between two hypothetical individuals (Becky & Amanda) who had a common friend. During this conversation, Amanda states that their friend is pirating music from the Internet, and Becky (who also illegally downloads music) can hypothetically give three alternative answers:

- Becky tells Amanda that pirating music is morally incorrect (hypocrisy).

- Becky says she never pirates music (lie).

- Becky omits her views or actions on this matter (control).

In the three situations, the last vignette shows that Becky gets home after meeting with Amanda and illegally downloads several songs from the internet. In their scores, respondents penalised (in increasing order of magnitude) controlling, lying and hypocritical attitudes (3). That is to say, people are predisposed to condemn hypocrites more strongly than liars, and hypocrites or liars more strongly than those who do not accuse others of committing those transgressions.

It should come as no surprise that politicians lie in electoral campaigns, yet win elections, e.g., Donald Trump’s ‘big-liar technique’ (4,5). At the very least, politicians can be censured by the media and social networks for not being exemplary about how their political rationale transcends their personal lives. In 2018, we witnessed this in Spain where Pablo Iglesias (former president of the left-wing party, Podemos, ideologically committed to defending the rights and earnings of the working class) was under fire, even from within his own party, for buying a house entailing a mortgage of €540K that very few in the working class could afford. Those criticisms never addressed whether the policies Iglesias advocates are beneficial for collective wellbeing or his income has been earned fairly.

Essentially, political adversaries mix honesty to draw public attention away from the marrow of societal problems. The most notorious case in the climate-change debate is Al Gore, 45th US Vice-President under Clinton’s presidency (1993-2001). Gore shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in recognition of his activism on climate change, which was featured in the Oscar-winning documentary An Inconvenient Truth. Not a coincidence, the same evening of the Oscar ceremony on the 25th February 2007, the Beacon Center of Tennessee published in its webpage the article: Al Gore’s personal energy use is his own “Inconvenient Truth” (6), where it was argued that Gore was using twenty times more energy (with the associated emission of greenhouse gases) than the average US household. And again, the week following the launch of Gore’s new documentary on climate change: An Inconvenient Sequel (01/08/2017) (7), the National Center for Public Policy Research in Washington flagged Gore’s energy expenditure at 19,241 kw (monthly average 34 times above the average US household), with an entire subsection detailing different aspects of Gore’s residential address, which was described as being “… in a 10,070-square-foot Colonial-style home in the posh Belle Meade section of Nashville, the eighth-wealthiest neighbourhood in America according to the U.S. Census Bureau” (8). The simple chain of connected thoughts that those messages unfold in many people’s minds is ‘Gore talks about climate change and Gore is a hypocrite, therefore climate change is irrelevant’. In other words, Gore’s behaviour becomes the fake representation of climate-change science.

Popular organisations in English-speaking countries, such as those in Tennessee and Washington, are think tanks of intellectuals who generate opinion over matters of public interest, and often act as lobbies towards political and economic outcomes. We googled the string ‘Al Gore’ AND ‘hypocrisy’ and obtained > 5.5 million hits (on May 2018). Most of the top hits did not devote much attention to climate science, or the environmental sensitisation posed by Gore — in many cases climate change was not even mentioned. Instead, the most frequent tenet was whether Gore was consistent in his personal life with what he defends as an environmentalist. Consequently, researchers from a uranium-rich country who propound (through data analysis and peer-reviewed work) the use of nuclear power to abate our current emissions of greenhouse gases (32.5 Gt in 2017 according to the International Energy Agency = 1.4 % higher than in 2016 when the Paris Agreement was signed) will be discredited as hypocrites. An so will politicians speaking out for the decarbonisation of our society (or collective wellbeing in general), but who are indicted in the public domain for having a huge carbon print. Data and science are then displaced to have a secondary or null role in critical discussions about what is best for our society.

Uncertainty is not a lack of rigour

To communicate climate change, we face an additional, major challenge. The climate system is extremely complex, so any analysis of climate shifts or trends incorporates uncertainty. How much might sea level rise? Where will droughts intensify? Why did a hurricane occur? What will the temperature of our atmosphere be in 50 years? To any scientist, uncertainty is not an obscure concept, but an obvious reality. In science, measuring the uncertainty of something is as important as measuring itself. And within the scientific community, we take for granted that researchers who evaluate the science of their peers, with its certain and uncertain elements, are driven by a search for knowledge (9) and thus reducing the subjectivity of our judgements.

Nevertheless, when science reaches the public domain, politicians, and citizens in general, can interpret uncertainty as an argument to prevent action — but is this interpretation against common sense? That is, if uncertainty makes scenarios of high environmental and social risk possible, should not such uncertainty inspire political and public engagement to mitigate potential negative impacts (10)? No one would rationally support the notion that if an oncological treatment was imperfect, such a treatment should be banned or no longer investigated, or interpreted as evidence that cancer does not exist.

Communicating climate change is challenging because uncertainty must reinforce what we already know about the fact that humans are disrupting the Earth’s climate (Box 1). In contrast, uncertainty has become a misinformation tool by so-called ‘merchants of doubt’ (11). Historians Naomi Oreskes & Erik Conway (see talk and movie trailer here and here) define them as scientific elites, with wide political connections, whose goal is prompting people to believe that no investment should be made into policies based on incomplete scientific knowledge (12). These authors have documented those elites in the US across a range of societal problems, namely space militarisation, tobacco, cancer, acid rain, the ozone hole, DDT-based insecticides, and global warming (11). The fact is that we already have the knowledge and technological kit to tackle and mitigate those serious problems (pointed out eloquently by Oreskes in this television interview)! Climate change, like cancer or poverty, are real measurable phenomena, not ethereal matters subject to faith, they do not belong to the territory of beliefs.

Perhaps the acid test between science and belief is precisely the treatment of uncertainty. For instance (see Box 2), and paradoxically, the language of the IPCC is more cautious and sceptical than that of those known as climate sceptics (13). In fact, we have found the IPCC’s reports conservative by overusing words of intermediate certainty to qualify the scientific evidence for climatic observations (14).

And so we enter the universe of jargon, wherein full taxonomies of terms confront a crowd questioning the science of climate change from different stances (e.g., contrarians, negationists, sceptics) with an opposing crowd supposedly exaggerating the scientific evidence for anthropogenic climate change (e.g., alarmists, catastrophists, warmists) (15). Labelling the attitudes with which scientists and, for that matter, any individual, intellectually balances the knowns and unknowns about climate change is a topic deserving discernment in its own right. However, such vocabulary polarises the public debate about climate change (15, 16) and so represents a further impediment for taking the (political) steps to avert the prevailing fossil fuel-dependent energy model.

Words are never innocent when money and power are at stake, and this is painstakingly true for the ongoing climate crisis. For that very reason, if we are the ones to talk or write about climate change, let’s think carefully what we say but especially how we say it (Box 1). If we are the ones to listen, let’s be alert that focusing our attention on the data, rather than on the informer, will always place us in a frame of mind closer to unbiased thinking.

Acknowledgements

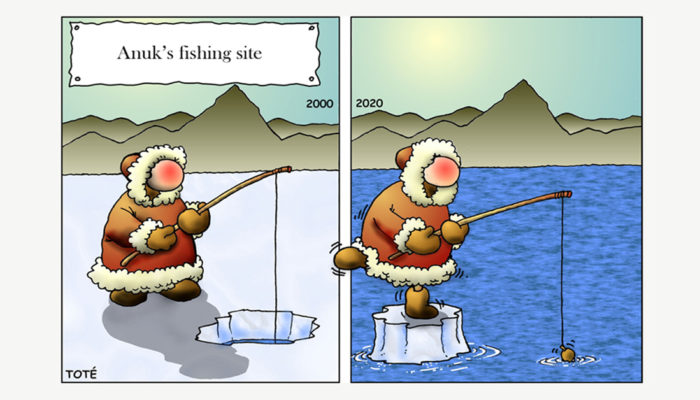

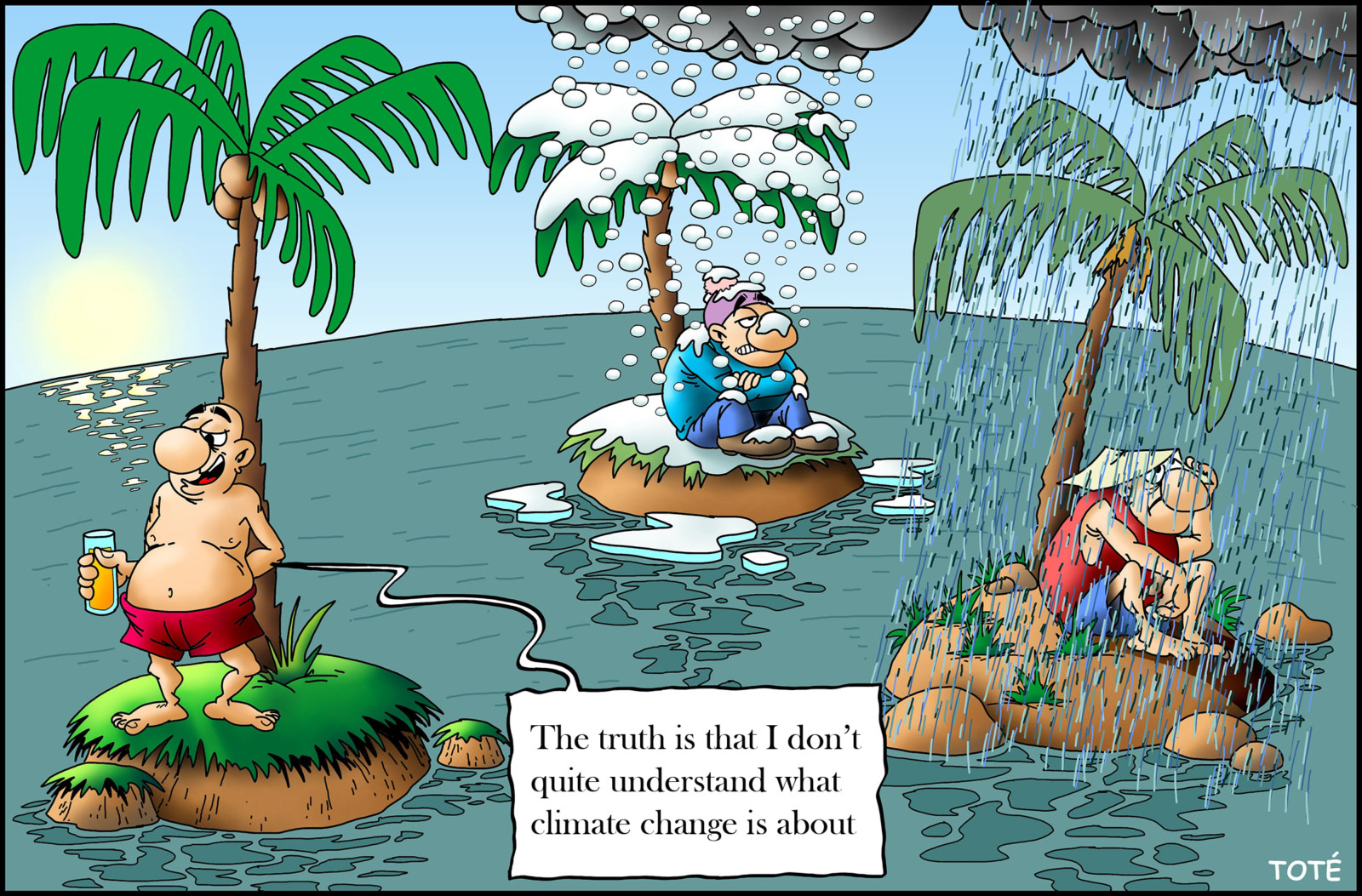

The idea of this blog resulted from a talk on polar bears for the Cabinet of Natural History, and a podcast on climate scepticism from the newspaper The Guardian. A Spanish version has been published in Quercus. We thank Adam Corner for revising the text in Box 1, and the British Ecological Society and the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness for financial support. Antonio Rodríguez Laiz Toté kindly provided the two drawings (www.elcomic.es).

BOX 1: Informing with uncertaintyWhen we give a talk, write, or give an opinion about climate change in a public space, we should consider that listeners and readers will unavoidably filter our messages through their academic, cultural, ideological and social status (17). The following 12 recommendations are nearly literal citations from the Uncertainty Handbook by Adam Corner and collaborators (18), guiding how to communicate the knowns and unknowns of climate-change science given the consensus about anthropogenic climate change prevailing in the scientific community (19, 20, 21). The Handbook is available online in Chinese, Dutch, English, French, German, Indonesian, Portuguese, and Spanish (translated by us).

1. Manage our audience’s expectations. Most sciences do not rest on definite (i.e., completely certain) facts. People want to hear that ultraviolet radiation causes skin cancer, but we can only say that exposure to such radiation increases the propensity of developing that type of cancer. Seemingly, most want to hear how many degrees the temperature will rise over the next half century, but we can only say that the magnitude of warming will depend on how much fossil fuel we burn (among other driving factors).

2. Start with what you know, not what you don’t know. The uncertainty about a topic does not invalidate the certainty about a different topic, but order matters in getting our message across; uncertainty will be better digested by an audience if following a sharp presentation of the main knowns.

3. Be clear about the scientific consensus. 97% of the scientific community agree that humans are altering the Earth’s climate (19), which is as true as claiming that smoking magnifies the incidence of lung cancer.

4. Shift from uncertainty to risk. The idea of risk calls for action, the idea of incomplete knowledge calls for inaction. Stating that flood risk is higher than ever due to climate change will resound in people’s minds rather than stating that floods are now more likely than in the past, although their potential impacts are known inaccurately.

5. Be clear what type of uncertainty you are talking about. For instance, we will normally lack the full set of data required to attribute a particular storm to climate change (the certainty is often low). But from first (physical) principles, we know that when air warms up, it can hold more water and chances of turning to a storm augment (the certainty is high).

6. Understand what is driving people’s views about climate change. We all perceive climate change through the lenses of our political convictions (22). Conservative thinking tends to doubt the real threats of climate change, so for our narrative to echo in that ideology it is helpful to insist in conserving natural beauty, mitigating risks, and increasing safety.

7. The most important question for climate impacts is ‘when’, not ‘if’. Many people understand climate change as a problem yet to come. Saying that sea levels will rise by 50 cm from 2050 to 2060 underlines the urgency of climate threads better than saying that sea levels will rise from 40 to 60 cm by 2060.

8. Communicate through images and stories. People do not interact with reality through histograms, probabilities or technical jargon. We must always illustrate technicalities with images familiar to our audiences and with examples of climate impacts that have occurred and been documented.

9. Highlight the ‘positives’ of uncertainty. In doing so, we might inspire hope and activism (23). For example, stating that if we act now the probability of drought is 20% less than stating that if we don’t act now, the probability of drought is 80 % (both statements announce the same probability).

10. Communicate effectively about climate impacts. If someone had a weak immune system and fell ill, nobody would question the causal role of immune failure in the disease. Likewise, we can mistrust someone affirming that a hurricane was a caused by climate change, but there is robust scientific evidence to state that climate extremes are enhanced by a warming atmosphere.

11. Have a conversation, not an argument. Many people do not talk or think much about climate change. To promote reflection, let audiences have their word to express their own perception of the (local) climate.

12. Tell a human story, not a scientific one. Listeners and readers must relate information on climate change to their daily lives, or to real stories involving real people suffering from climate impacts. We urgently need to shift climate change from a scientific to a social reality.

BOX 2: Polarisation in climate science: ‘alarmists’ versus‘ contrarians’?The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the leading international body providing governments with periodical assessments of the published science of climate change, its impacts and future risks, and options for adaptations and mitigation (www.ipcc.ch). Its latest* Fifth Assessment Report, the IPCC concludes that [Synthesis Report] ‘… Human influence on the climate system is clear, and recent anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases are the highest in history. Recent climate changes have had widespread impacts on human and natural systems’ (24), aligning with the overriding scientific evidence (19). Therein, a calibrated language is used to rank explicitly the uncertainty of climate findings, rates and trends (25). IPCC reports are policy-relevant and, being free and public, stand open to general scrutiny, while IPCC processes and procedures have been reviewed externally (26). The Nongovernmental Panel on Climate Change (NIPCC) defines itself as “… an international panel of nongovernment scientists and scholars who have come together to understand the causes and consequences of climate change. Because we are not predisposed to believe climate change is caused by human greenhouse gas emissions, we are able to look at evidence the IPCC ignores”, and “… able to offer an independent ‘second opinion’ of the evidence reviewed — or not reviewed — by the IPCC on the issue of global warming” (NIPCC’s website accessed on May 2018). Hosted by the Heartland Institute, the NIPCC has published several reports (e.g., Heartland Institute and NIPCC report), arguing for “… deep disagreement among scientists on scientific issues that must be resolved before the man-made global warming hypothesis can be validated. Many prominent experts and probably most working scientists disagree with the claims made by the IPCC” (17). * The release of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report is scheduled for late 2022 to early 2022.

This blog was edited by the editorial board.

References:[1] Herrando-Pérez, S. & Vieites, D. R. (2017). Comer o perecer en un mundo sin hielo. Quercus 372: 68-70. See English version here. [2] Brook, B. W. & Bradshaw, C. J. A. (2015). Key role for nuclear energy in global biodiversity conservation. Conservation Biology 29: 702-712. [3] Jordan, J. J. et al. (2017). Why do we hate hypocrites? Evidence for a theory of false signaling. Psychological Science 28: 356-368. [4] Ahmadian, S. et al. (2017). Explaining Donald Trump via communication style: grandiosity, informality, and dynamism. Personality and Individual Differences 107: 49-53. [5] Peters, M. A. (2017). Education in a post-truth world. Educational Philosophy and Theory 49: 563-566. [6] Beacon Center of Tennessee (2007). Al Gore’s personal energy use is his own “Inconvenient Truth” (Nashville, USA, 2007). [7] Mann, M. E. (2017). Climate change: Al Gore gets inconvenient again. Nature 547: 400-401. [8] Johnson, D. (2017). Al Gore’s inconvenient reality: the former Vice President’s home energy use surges up to 34 times the national average despite costly green renovations. National Policy Analysis 679 (National Center for Public Policy Research, Washington, USA). [9] Metz, M. (2002). Criticism preserves the vitality of science. Nature Biotechnology 20: 867. [10] Lewandowsky, S. et al. (2015). Uncertainty as knowledge. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 373: 20140462. [11] Oreskes, N. & Conway, E. M. (2010). Merchants of Doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming (Bloomsbury Press, London, UK), pp. 355. [12] Oreskes, N. & Conway, E. M. (2010). Defeating the merchants of doubt. Nature 465: 686-687. [13] Medimorec, S. & Pennycook, G. (2015). The language of denial: text analysis reveals differences in language use between climate change proponents and skeptics. Climatic Change 133: 597-605. [14] Herrando-Pérez, S. et al. (2019). Statistical language backs conservatism in climate-change assessments. Bioscience 69: 209-219. [15] Howarth, C. C. & Sharman, A. G. (2015). Labeling opinions in the climate debate: a critical review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 6: 239-254. [16] O’Neill, S. J. & Boykoff, M. (2010). Climate denier, skeptic, or contrarian? Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 107: E51. [17] Idso, C. D. et al. (2015). Why scientists disagree about global warming. The NIPCC report on scientific consensus (The Heartland Institute, Illinois-USA). [18] Corner, A. et al. (2015). The Uncertainty Handbook (University of Bristol, UK), pp. 19. [19] Cook, J. et al. (2013). Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature. Environmental Research Letters 8: 024024. [20] Cook, J. et al. (2016). Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters 11: 048002. [21] Oreskes, N. (2004). The scientific consensus on climate change. Science 306: 1686-1686 [22] Kahan, D. M. et al. (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change 2: 732-735. [23] Morton, T. A. et al. (2011). The future that may (or may not) come: how framing changes responses to uncertainty in climate change communications. Global Environmental Change 21: 103-109. [24] IPCC (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report (IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland). [25] Mastrandrea, M. D. et al. (2011). The IPCC AR5 guidance note on consistent treatment of uncertainties: a common approach across the working groups. Climatic Change 108: 675-691. [26] InterAcademy Council (2010). Climate change assessments. Review of the processes and procedures of the IPCC (Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

David Crookall

Wonderful piece. Thank you.

CfP: Special issue of an EGU journal on climate and ocean education.

To combat climate change and ocean degradation, people need to learn. We are inviting contributions to a special issue of the EGU journal ‘Geoscience Communication’ on the theme of climate and ocean education (literacy). The CfP is available when you fill out this short form https://forms.gle/wExv7amY95qHXCop8, and directly here https://oceansclimate.wixsite.com/oceansclimate/gc-special.

Please share this. Thank you.