Our Editor, Ben Fisher, writes about his experience as an observer at COP26 and the representation of biogeosciences in the negotiation area.

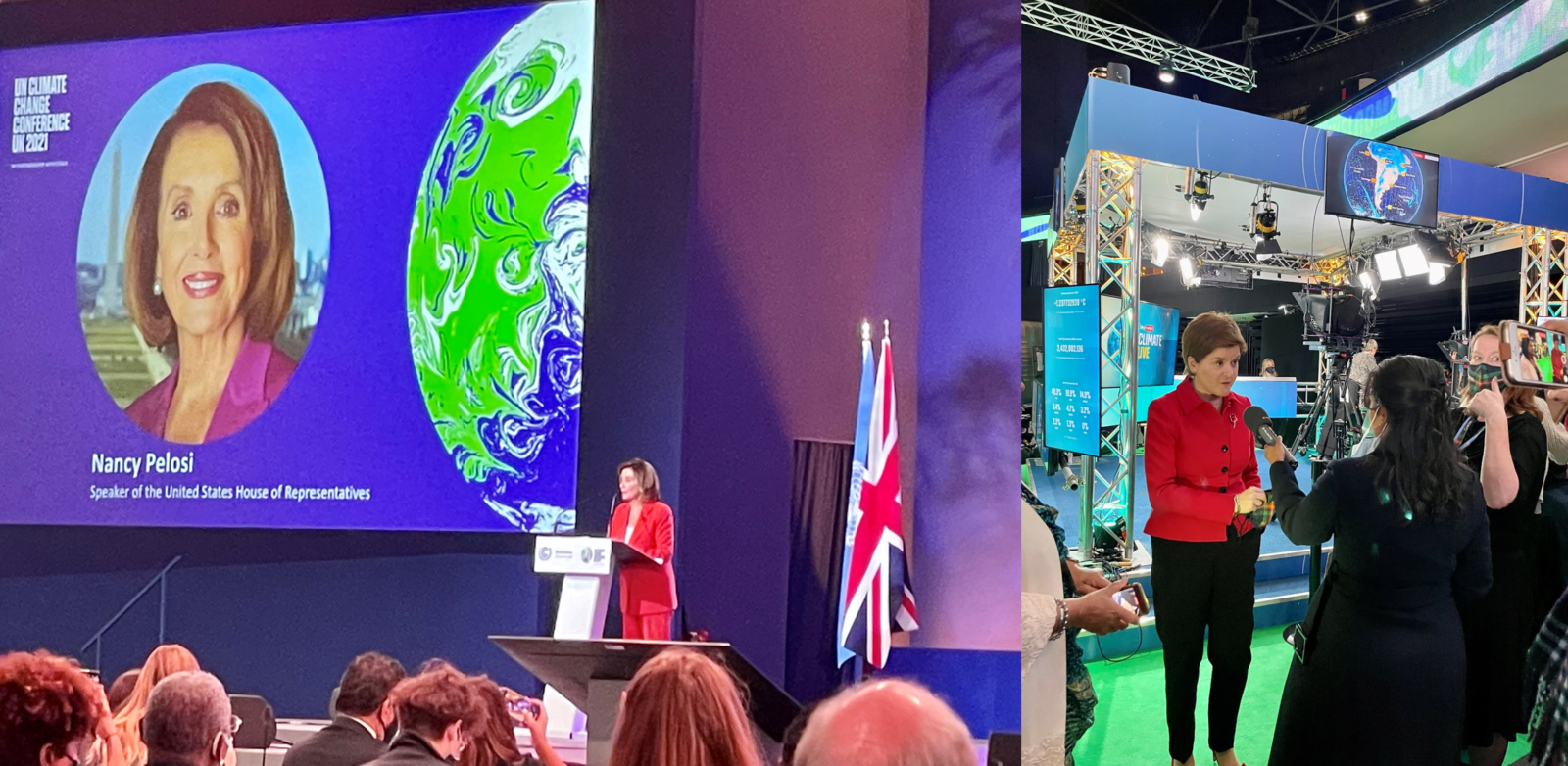

I was extremely fortunate to have the opportunity attend the second week of COP26 as a delegate of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR). Having been a rather last minute addition to the attendance list (I found out I’d got credentials about 2 hours before arriving!), and as someone who hadn’t been to a COP before I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect beyond the exterior ring of steel, UN police and airport style security. I arrived to find myself among the world’s media, representatives of all 197 parties of the UNFCCC, and the occasional famous face including Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, Former US President Barack Obama and US Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi to name a few!

Nancy Pelosi speaking on gender day (L) and Nicola Sturgeon giving an interview on climate finance (R)

COP is split in to 2 main zones with the Green (public) Zone containing much of the exciting science and outreach activities and the Blue Zone being more focused on translating this science in to policy. The Blue Zone is then further split in to roughly 4 different areas, each connected with some heavy duty tents to protect us from the worst of the Scottish weather. The first, and probably most photographed area of COP is the global action hub which serves as the backdrop for most news reporting, meaning you often caught an off camera look at someone being interviewed on TV, I’m sure I’ve appeared in the background of many news channels!

In the middle of the global action hub hung a giant rotating Earth, reminding us all the reason we were gathered here. As an Antarctic scientists myself and my colleagues were keen to get a view from the bottom of the Earth! I’m pictured here with my supervisor Dr Sian Henley, and fellow cryosphere PhD students Morag Fotheringham and Bryony Freer. They all do really cool work (literally!), check out the links to their profiles.

The pavilions were by far the largest area of COP and could easily be confused for a maze, this area is probably most similar to other conventions expect nobody was trying to sell anything here. In fact talking nicely to most pavilions often got you a free treat from the respective countries. Each country hosts a pavilion in addition to several NGO’s and a few themed areas such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and Cryosphere pavilions.

Each pavilion hosts a range of activities and most had their each own daily programme of talks (called side events). The UK presidency pavilion for example had this interactive globe which allowed you to load different sets of European Space Agency data and explore data trends around the world, I suggested that I’d be more than happy to receive one of these for Christmas. While other countries such as Tuvalu brought a more hard hitting message about the state of the climate in the form of these lifejacket-clad polar bears.

Several of the pavilions enthused the biogeochemist in me, with excellent talks being given in the Cryosphere, Peatlands, Water and Science pavilions. You can still check out all the event from the Cryosphere pavilion on their YouTube channel.

Further down the hall we get to the business end of COP. Away from the glitz and glammer of the pavilion’s many of the important decisions are taken in hidden away, rather clinical cardboard walled rooms. Once these decisions have been drafted, or if someone important has something to say, then delegates would be brought to one of two plenary rooms. These giant halls represent a make-shift UN HQ with each country having a reserved spot, meaning I got to pretend to be a different country each day from my observers seat in the second row. In these large sessions we heard from panels discussing the theme of the day, my personal favourite was probably the discussions held on gender day featuring a keynote from Nancy Pelosi. In contrast, I also sat through several hour long sessions of negotiators debating the placement of commas and whether the word ‘urge’ or ‘request’ was more forceful in the final text, these sessions were essentially like writing a paper with 196 co-authors who all happened to be grammar fanatics. Far more interesting than the textual debate was watching the interactions between those in the room, at one point US climate envoy John Kerry came to have a conservation with the EU’s Executive Vice President Frans Timmermans who was sat a few seats along from me, I remarked that I’d love to know how much the handshake following that conversation was worth.

Entering the world of science policy by attending my first (and hopefully not last) COP was definitely a case of jumping in at the deep end. Despite it being a tiring week it was incredibly eye-opening to see the way in which decision makers actually use the science we create to inform policies. It made me realise that although it can often feel like we work on the smallest of scientific questions, cumulatively these add up, and that people do care deeply about climate science, particularly small and developing countries who we don’t hear from enough on the scientific stage.

One of the difficulties I found with COP is that it has been hard to juggle attending as a scientific delegate and being an individual young person with my personal opinions on the policies I’d like to see implemented. When someone hears that you’ve been to COP they generally want to know whether you think it was a success or not. As an observer, I’ve chosen to reserve judgement on my opinion for now, partly because much of the last week was a blur and partly because I’m not best placed to understand the intricacies of the policy decided upon. More fundamentally however, I think we will only be able to judge the success of the decisions made in Glasgow once countries have had the opportunity to implement the policies they decided upon, after all it takes actions not words to tackle climate change. However, I do know that it has been a privilege to be in the same room that these talks have taken place in and regardless of the success I hope to be able to use this experience to really enhance the way I engage with policy as a scientist as well as using my experience to inform my teaching on science and policy. I also believe that we can learn a lot from the way COP manages to get a much wider and more representative cross section of the population in the room in a way that science often does not. I am now looking forward to seeing how the decisions taken in Glasgow develop over the coming months and engaging with the COP’s that will follow.