Post by Mark Cuthbert, Research Fellow and Lecturer at Cardiff University, in the United Kingdom, and by Gail Ashley, Distinguished Professor at Rutgers University, in the United States.

_______________________________________________

During the dry season, Lake Masek in Northern Tanzania (see map) is a lovely place to be if you’re a hippo or a flamingo, but for humans it’s an inhospitable environment. We were on ‘safari’ (a scientific one of course, but the wildlife was a massive bonus! Photo 1-left) to try and better understand the distribution of freshwater in this dryland landscape.

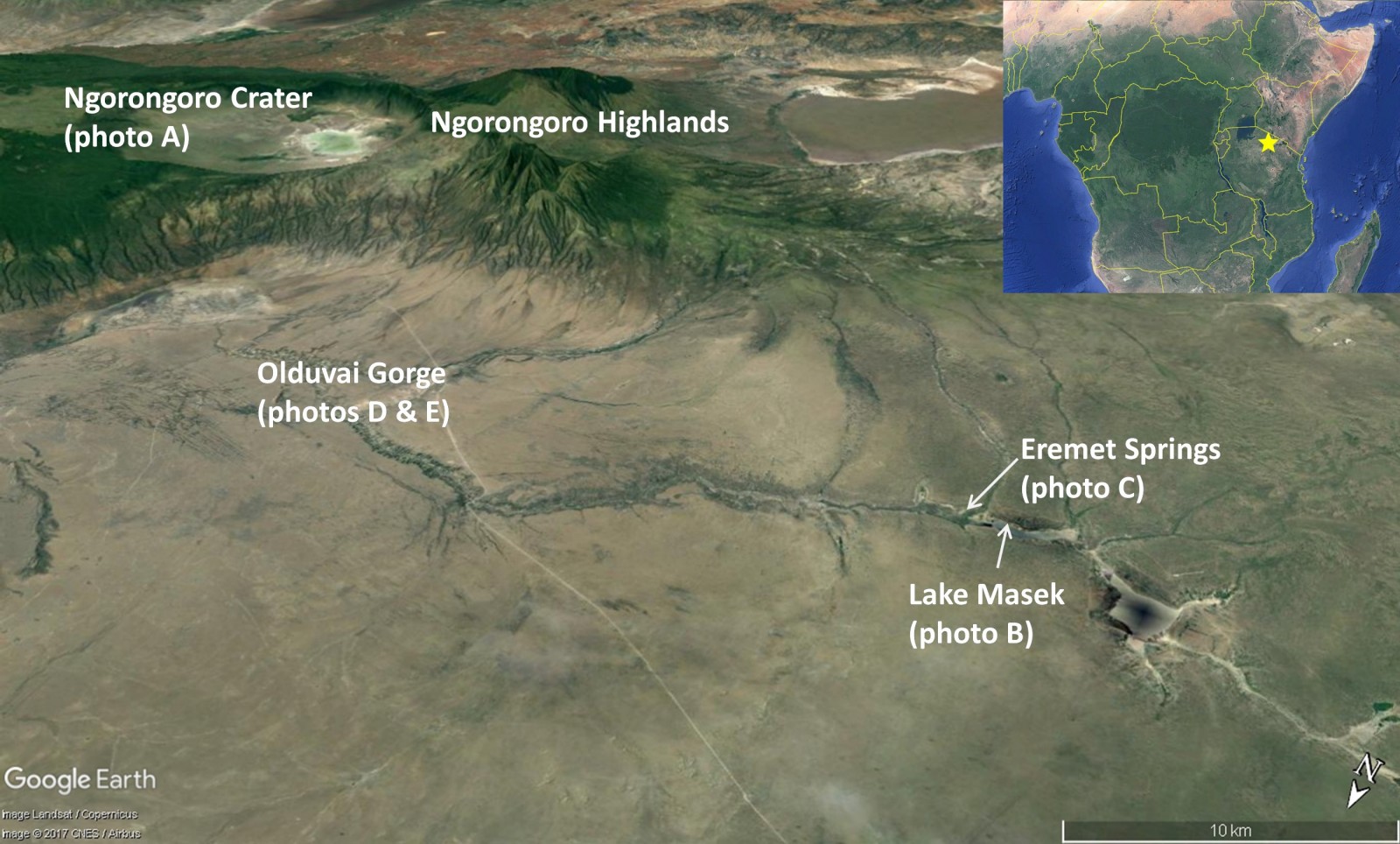

Map: Locations on our groundwater safari in Northern Tanzania.

Watching our backs in case of predators, we ventured out of the safety of our Land Rover for Gail to sample the lake water, as salt blew in drifts around us off the desiccated edges of the lake bed (Photo 1-right). It was very salty and not potable for humans. All the streambeds that run into the lake were dry and yet our Masai guide told us that nearby we could find freshwater all year round.

Photo 1: (L) The amazing wildlife in the Ngorongoro Crater & (R) Saline-alkaline Lake Masek.

Intrigued, we set off around the edge of the lake and as we came over the crest of a small ridge were met with the most remarkable site – 1000s of cattle and goats queuing up for water from pools on the edge of the dry river valley just downstream of the lake. We waited for the queues of animals to die down and asked permission from the local guardians of the water source to investigate (Photo 2). The pools turned out to be fed from groundwater flowing out of rocks at the side of the valley. In contrast to the salty water from the adjacent lake, these springs were fresh and potable. We think the water is very old having originally fell as rain on the flanks of the ancient Ngorongoro Highlands (see map) before flowing slowly under gravity through layers of volcanic rocks 10’s of km to the springs. Because there’s so much groundwater stored in these rocks, and because they are not very permeable, the water seeps out quite slowly. So the springs keep running all through even the longest droughts and are vital water supplies for local people.

Photo 2: Asking permission to sample at Eremet springs

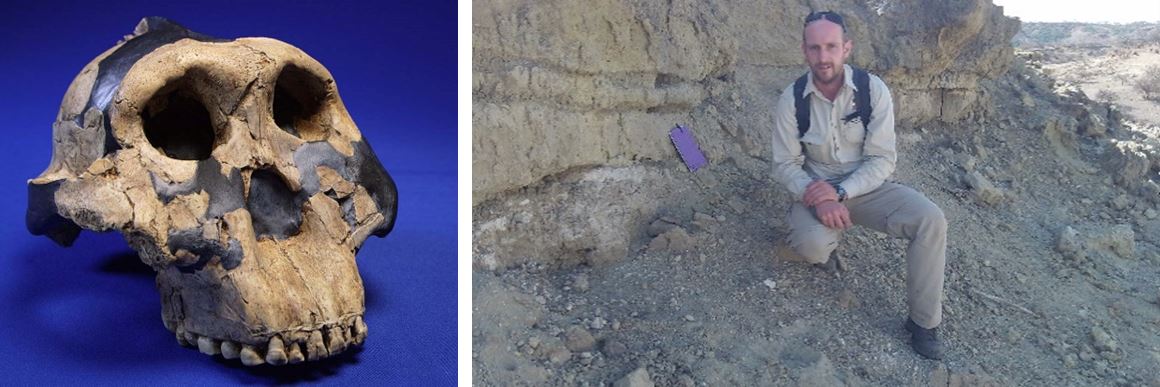

We travelled east along the same dry river valley in which we’d encountered the springs. Here the river, which only flows during the wet season, has cut itself into a steep ravine called Olduvai Gorge. We walked down the side of the gorge travelling back in time ~2 million years, the rocks and sediments around us telling a well-documented story of how the environment has changed over that time. Many exciting fossil discoveries have also been made in the gorge including some of our oldest human ancestors (Photo 3-left). For us one of the most interesting discoveries was geological evidence of ancient springs (Photo 3-right) found in the same layers as fossil human ancestors and stone tools which Gail has documented going all the way back to nearly 2 million years ago (read more here). There are clues from the surrounding sediments that there was a lake nearby but it was salty and alkaline, and we think the springs would have kept flowing for 100s or even 1000’s of years during persistently drier periods experienced in the past (read more here).

The springs that were flowing in the Olduvai area 2 million years ago, just like the springs on the margins of present day Lake Masek, would have been the only freshwater for miles around and vital for sustaining life during dry periods. Since there are hundreds of freshwater springs dotted around present day drylands in the East African rift system, we can hypothesise that during dry periods in the past, similar locations would have acted as ‘hydro-refugia’ – places where animals could find the necessary freshwater for survival in an otherwise dry landscape. In dry periods there would be lots of competition for these resources and populations would have become isolated from each other for quite long periods. During wetter periods springs would have enabled our ancestors and other species to move long distances across the East African landscape and beyond, acting like stepping stones connecting river corridors and lakes and enabling populations of different species to encounter one another (read more here). Groundwater was likely therefore an important control on the movement and evolution of humans in this environment.

Photo 3: (L) Paranthropus boisei (‘Zinj’) hominin skull found at Olduvia gorge (Photo Credit: Tim White PhD, Human Evolution Research Center, University of California, Berkeley) & (R) Mark Cuthbert next to a tufa (calcium carbonate) deposit thought to be evidence of groundwater discharging near the site that the Zinj fossil was found.

Groundwater is often ‘out of sight and out of mind’. Our safari gave us a glimpse into its importance in sustaining life in a dryland environment not just in the present day, but also for our ancestors going back at least 2 million years through some climatically turbulent periods. The challenge going forward is how that groundwater resource can be protected to make sure it’s there when it’s needed in the face of an uncertain climatic future.

Acknowledgements: it has been a massive privilege to be able to explore this landscape and ponder how freshwater has shaped life here over millions of years. Particular thanks to our guides Joseph Masoy and Simon Matero, logistical support from Charles Musiba (LOGIFS – Laetoli-Olduvai Gorge International Field Camp) and TOPPP (The Olduvai Paleoanthropological and Paleoecological Project), our hosts at the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority, and all our collaborators on the papers cited.

_______________________________________________

Mark Cuthbert is a Research Fellow and Lecturer in the

Mark Cuthbert is a Research Fellow and Lecturer in the

School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom. Mark’s work currently focuses on coupled hydrological-climate process dynamics in order: to understand & quantify groundwater sustainability; to improve interpretations of terrestrial paleoclimate proxy archives; to understand Quaternary paleoenvironments & how they influenced our evolution as a species. Read more on Mark by clicking on the links below.

Gail M. Ashley is a Distinguished Professor and Undergraduate Program Director of Quaternary Studies Program at Rutgers University, in the United States. Gail studies modern physical processes and deposits of glacial, fluvial, lacustrine, arid landscapes, and use this information to interpret paleoenvironments. Read more about Gail by going to her research website.

Gail M. Ashley is a Distinguished Professor and Undergraduate Program Director of Quaternary Studies Program at Rutgers University, in the United States. Gail studies modern physical processes and deposits of glacial, fluvial, lacustrine, arid landscapes, and use this information to interpret paleoenvironments. Read more about Gail by going to her research website.

THIMMARAJU MOHAN

What is the difference between Magmatic waters and a new research termed CRUSTUAL WATERS

REGARDS