As more people move to urban areas, cities around the world are experiencing increased water stress and looking for additional water supplies to support their continued grow.

The first global database of urban water sources and stress, published online this week in Global Environmental Change, estimates that cities move 504 billion litres of water a distance of 27,000 kilometers every day. Laid end to end, all those canals and pipes would stretch halfway around the world. While large cities occupy only 1% of the Earth’s land surface, their source watersheds cover 41% of that surface, so the raw water quality of large cities depends on the land use in this much larger area.

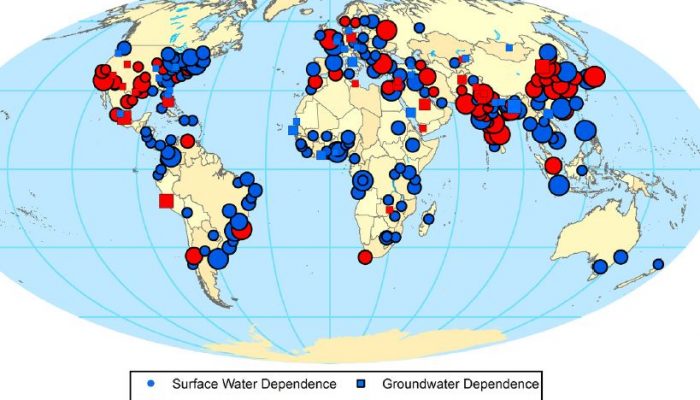

An international team of researchers from nine institutions, including McGill University in Montreal, surveyed and mapped the water sources of more than 500 cities, providing the first global look at the water infrastructure that serves the world’s large cities. The study was led by Rob McDonald, senior scientist with the Nature Conservancy in Arlington, Va.

Prof. Bernhard Lehner and PhD student Günther Grill of McGill’s Department of Geography contributed a detailed global map of rivers, lakes and watersheds to help map the water sources of each city, while Prof. Tom Gleeson of McGill’s Department of Civil Engineering conducted analysis for groundwater sources.

The research team used computer models to estimate the water use based on population and types of industry for each city, and defined water-stressed cities as those using at least 40% of the water they have available. Previous estimates of urban water stress were based only on the watershed in which each city was located, but many cities draw heavily on watersheds well beyond their boundaries. In fact, the 20 largest inter-basin transfers in 2010 totaled over 42 billion liters of water per day, enough water to fill 16,800 Olympic-size pools.

There is good news in the findings: Many cities are not as water-stressed as previously thought. Earlier estimates put approximately 40% of cities into the water-stressed category. This analysis has the number at 25%.

The study finds that the 10 largest cities under water stress are Tokyo, Delhi, Mexico City, Shanghai, Beijing, Kolkata, Karachi, Los Angeles, Rio de Janeiro and Moscow. (Neither of the two Canadian cities analyzed — Toronto and Montreal — was water-stressed, according to the definition used in the study.)

The study also makes clear the extent to which financial resources and water resources are intertwined. It is possible for a city to build itself out of water scarcity — either by piping in water from greater and greater distances or by investing in technologies such as desalinization — but many of the fastest growing cities are also economically stressed and will find it difficult to deliver adequate water to residents without international aid and investment.

“Cities, like deep rooted plants, can reach a quite a long distance to acquire the water they need,” says McDonald. “However, the poorest cities find themselves in a real race to build water infrastructure to keep up with the demands of their rapidly growing citizenry.”

The study also reveals that:

- Four in five (78%) urbanites in large cities, some 1.21 billion people, primarily depend on surface water sources. The remainder depend on groundwater (20%) or, rarely, desalination (2%).

- The urban water infrastructure of large cities cumulatively supplies 668 billion liters daily. Of this, 504 billion liters daily comes from surface sources, and that water is conveyed over a total distance of 27,000 km.

- Land use in upstream contributing areas affects the raw water quality and quantity of surface water sources.

- An estimated one-quarter of large cities in water stress contain $4.8 trillion of economic activity, or 22% of all global economic activity in large cities. This large amount of economic activity in large cities with insecure sources of water emphasizes the importance of sustainable management of these sources, not just for the viability of individual cities but for the global economy.

The research was supported by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

———-

“Water on an urban planet: urbanization and the reach of urban water infrastructure,” Robert. I. McDonald, et al, Global Environmental Change, published online June 2, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.022