Original Article by Andy Baker and Margaret Shanafield

Cities are home to about half of the global population and urban population has doubled in the last 50 years from 1.5 billion people in 1975 to 3.5 billion people in 2015. This urban population will rise to a predicted 5 billion people by 2050. So, it’s probable that most of us will be reading this from a city. So, city dwellers, do you know how deep your groundwater level is? And is it rising or falling?

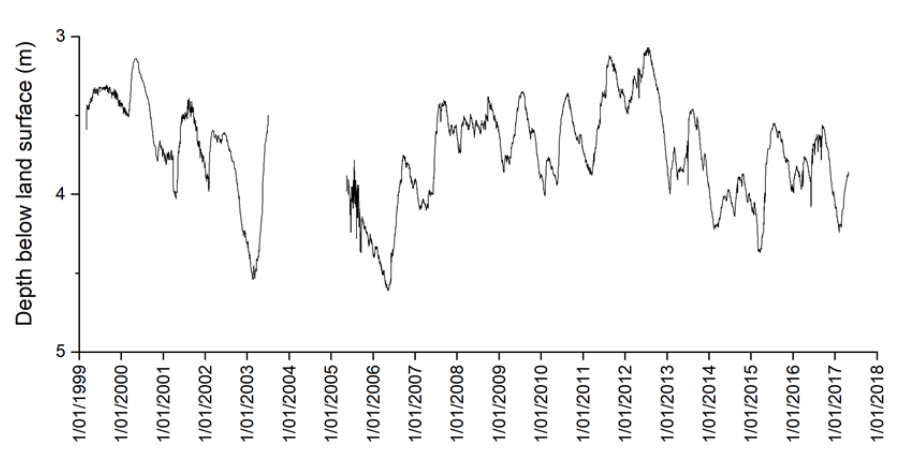

Figure 1. Groundwater levels in Sydney’s Botany Sands Aquifer, which is only a few meters below land surface. Rapid rises in groundwater occur after periods of wet weather; such as 600 mm of rainfall in April and May 2003. Data © WaterNSW reproduced under CC 4.0

It is often written that groundwater is a hidden resource. But in urban areas, when there is a protracted fall in groundwater levels, subsidence may occur. A recent paper published in the journal Science mapped subsidence at a global scale and identified that the most common cause was excessive groundwater extraction. You can explore an interactive map here.

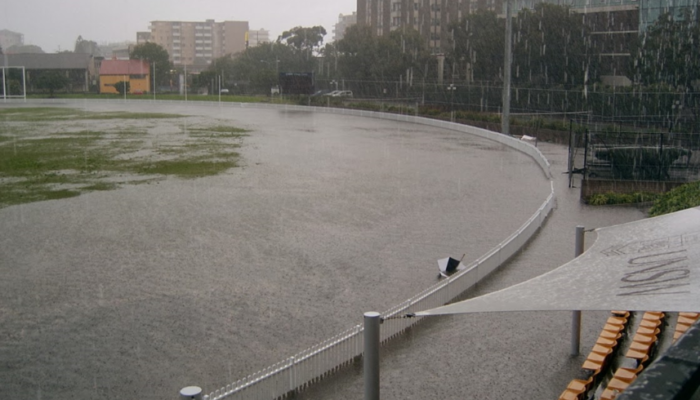

Many people don’t realise groundwater flooding can also occur. When groundwater rises close to the land surface, it could have unwanted consequences, including damage to infrastructure such as flooded basements and tunnels; loss of amenities, such as flooding of underground venues; and groundwater entering storm and waste water management systems.

So how and why do changes in groundwater level occur in urban areas?

In some cities, continued over-abstraction of groundwater can lead to a fall in groundwater levels. An often-cited example is that of Bangkok, where over-abstraction brought the groundwater level down to around 40 m below the surface, leading to subsidence and saltwater intrusion. This trend was successfully reversed by better regulatory management of the groundwater resource.

Alternatively, groundwater levels may progressively rise closer to the land surface over time. Typically, this is due to the cessation of over-abstraction, firstly as water-intensive manufacturing industries close or move away from an urban area, or secondly, if the urban groundwater resource becomes too contaminated to abstract. Here in Sydney, this has occurred in the Botany Sands Aquifer. Once the water supply for the city, industrial pollution has led to a restriction to licensed abstraction. Decreased abstraction has led to rises in groundwater level even in periods of long-term drought.

Figure 2 No play today. Groundwater flooding in Sydney in 2007. (Photo: Ian Acworth)

In some locations, where the groundwater level is naturally close to the surface and there is a strongly seasonal climate, a seasonal variation in groundwater level can be expected and planned for. An example here in Western Australia is that of the city of Perth, that has a seasonal Mediterranean climate type with wet winters and dry summers, and associated rises and falls in groundwater. Long term rises in groundwater are trickier to manage.

Another consideration for cities is climate change, and how that might affect both groundwater recharge and abstraction. For example, back in Western Australia, the Perth region has experienced a long-term decline in winter rainfall that has been attributed to global warming, and rainfall recharge of groundwater is decreasing. In contrast, over on the east of the continent, Sydney has experienced a run of wetter years, thanks to the rare occurrence of repeat La Niña and negative Indian Ocean Dipole phenomena that bring increased moisture to the region. Sydney has just experienced its wettest start to a year on record with 1531 mm of rainfall through to the end of May, and the Botany Sands Aquifer has been on the rise.

So, what’s happening below YOUR feet?