Post by Margaret Shanafield, ARC DECRA Senior Hydrogeology/Hydrology Researcher at Flinders University, in Australia. You can follow Margaret on Twitter at @shanagland.

___________________________________________________________

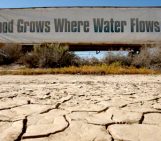

What led me down the slippery slope into a career in hydrology and then hydrogeology, was a desire to combine my love of traveling with a desire to have a deeper relationship with the places I was going, and be able to contribute something positive while there. I figured everyone needs water, and almost everyone has either too much (flooding) or too little of it.

But, from an academic point of view, aid/humanitarian/philanthropic projects can be frustrating and offer few of the traditional paybacks that universities and academia reward. Last week, for example, I spent much of my time working on the annual report for an unpaid project, and I am soft money funded. And what’s worse, I couldn’t even get the report finished, because most of the project partners hadn’t given me their updates on time. When I went across the hall to complain to my colleague, he admitted that he, too, was in a similar situation.

So what is the incentive?

Globally, the need for regional hydrologic humanitarian efforts is obvious. Even today, 1,000 children die due to diarrhoeal diseases on a daily basis. Water scarcity affects 40% of global population, with 1.7 billion people dependent on groundwater basins where the water extraction is higher than the recharge. And, the lack of water availability is only going to get worse into the future.

But being a researcher with pressure to “publish or perish” and find ways to fund myself and my research, what was/is my incentive to address these problems? From an academic point of view, water aid projects are often time-consuming, with expected timelines delayed by language and cultural barriers, difficulties in obtaining background data, expectations on each side of the project not matching up, and activities and communication not happening on the timescales academics are used to. And the results are typically hard to publish.

An online search revealed numerous articles discussing the pros and cons of pursuing a career in development work, including: having a job aligned with one’s morals and values, an exciting lifestyle full of change, motivated co-workers, the opportunity to see the world and different cultures, the opportunity to make a difference, and last but not least, because it is a challenge (in a good way).

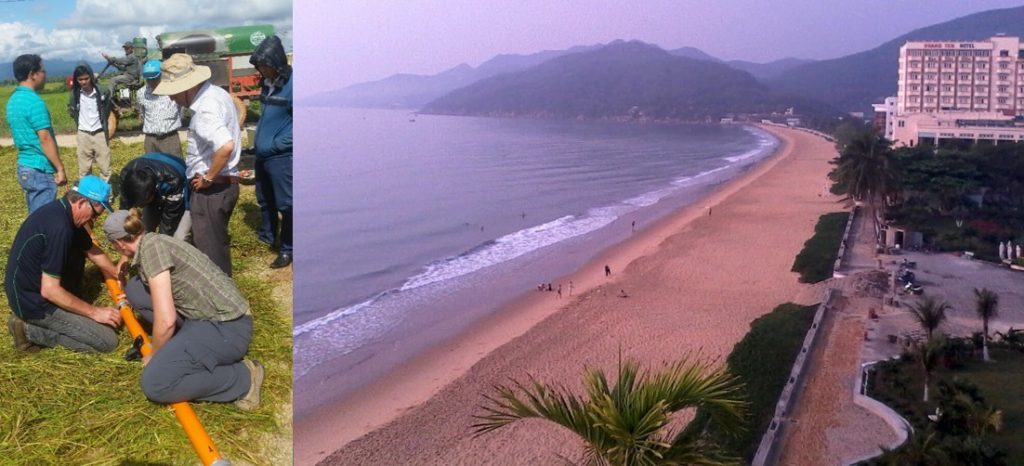

As a scientist, I get elements of all these pros in my daily work. But, while much of what academics do fits under the umbrella of “intellectually challenging”, aid projects provide applied problems with real-world implications that can sometimes be lacking in the heavily research-focused academic realm, except for the creative “broader impacts” and outreach sections of grant proposals. They are therefore an opportunity for scientists to have an impact on the world by contributing to the collective understanding of water resources and hydrologic systems. And hey, many of us enjoy travelling and get to visit interesting places for work, too.

Pulling myself out of my philosophical waxings, I focused on these highlights and the benefits of working in an interdisciplinary project to address some of those global problems I mentioned earlier – and got back to report writing.

Training project partners in Vietnam to take shallow geophysical measurements (left). Sweaty days in the field are rewarded by cheap beers, magnificent sunrises, and relaxing evenings at the coast where the river meets the sea (right). Photos by M Shanafield.

___________________________________________________________

Margaret Shanafield‘s research is at the nexus between hydrology and hydrogeology. Her current research interests still focus on surface water-groundwater actions, although she work’s on a diverse set of projects from international development projects to ecohydrology. The use of multiple tracers to understand groundwater recharge patterns in streambeds and understanding the dynamics of intermittent and ephemeral streamflow are her main passions. Since 2015, she has been an ARC DECRA fellow, measuring and modelling what hydrologic factors lead to streamflow in arid regions. You can find out more about Margaret on her website.